The mass job losses triggered by the pandemic have exposed the art sector’s lamentable approach to human resources, with reports of poor redundancy procedures, pressure to sign stringent non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), paltry pay-offs and unsafe working conditions.

“We’re going to be living with litigation from the pandemic for many years to come,” says Simon Gorham, the head of employment at the London-based law firm Boodle Hatfield. He sees a “big increase” in unfair dismissal cases, particularly those linked to whistleblowing and health and safety. “People feel unsafe going into the work place so they’ve stopped going in, then been sacked or made redundant,” he says.

Employees’ legal rights in the UK and the US (and across the states) vary greatly. For example, in the US, there is widespread use of arbitration clauses, so we hear little about employment disputes. One former employee of a blue-chip Los Angeles-based gallery, who started legal action against the firm last year after being laid off, says: “If a dispute does go to court, the arbitration agreement means you don’t get a jury. And… juries tend to side with the employees.” Such privacy is prized, he says, “because these galleries have a lot to hide and once the lawsuit starts and you start… digging into what happened, everything about the business can be revealed.” Like many who have lost their jobs, he is disillusioned with an art world that uses a “guise” that people are working “for the greater good… to get away with unfair and illegal work practices.” He adds: “I’ve pulled the curtain back and seen who the wizard really is. I’ve had enough, and if that means other galleries or museums don’t want to hire me, then it is what it is.”

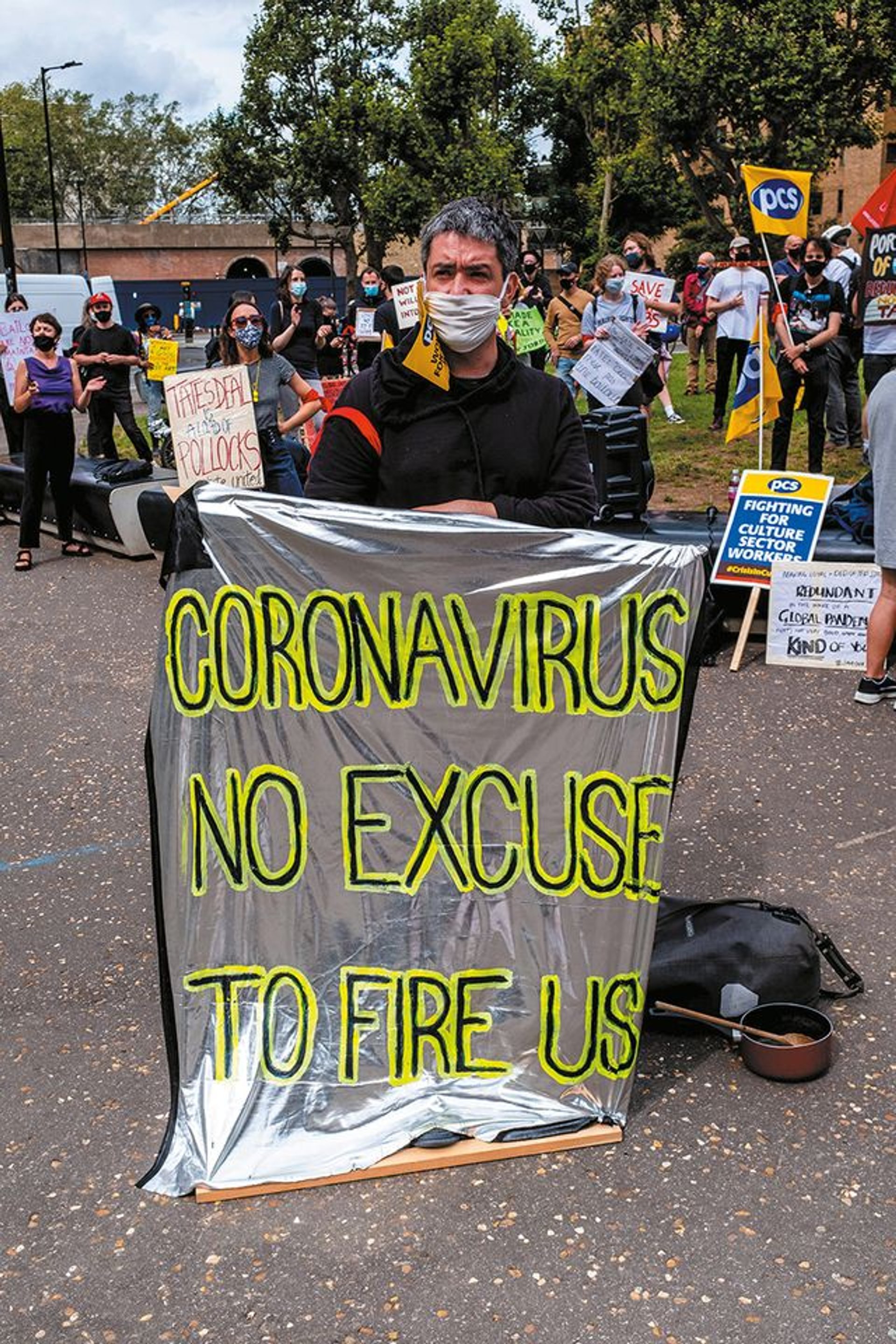

Workers and supporters at Tate Modern in London protest against job cuts last summer © Grant Rooney / Alamy Stock Photo

Junior staff at highest risk

Those in the lowest ranks are most vulnerable to poor treatment. As the art lawyer Jon Sharples of London-based Canvas Art Law points out: "It is a very stark fact in English employment law that you have almost no right to be treated fairly until you have two years’ service (although a discrimination claim can be brought at any time before that)." In Sharples’s view, this “disproportionately affects the art world as turnover of people and moving around is higher than in other sectors”. The result, he says, is a “moral hazard for managers and boards because they can fire people without any due process, at the height of a pandemic, without any real legal risk.” He says “the clock doesn’t start running on the two years’ service during an internship”. Therefore, “in the race to the bottom of working conditions, the bottom rung in the arts is lower than in most other sectors.”

Covid-secure working conditions are another major concern. One employee at London’s Tate says: “I know of back-room staff who have faced pressure from senior management to continue with on-site activity because it is considered income-generating. A lot of us feel really concerned by this and don’t feel that those concerns are being heard—particularly as we’re at the end of the voluntary redundancy process.”

In response, a Tate spokesperson says: “Colleagues are only asked to be on site if their work is deemed essential and where this work cannot be done remotely. We continue to keep all work on site under close review and are working closely with our unions on this. Stringent measures are in place to ensure our colleagues’ safety and well-being and we constantly monitor feedback from the staff involved to take account of individual circumstances.”

Freelance workers, meanwhile, often have little or no legal recourse due to the itinerant nature of their employment. One freelance technician who has worked with a major international contemporary art gallery in the UK says: “At first they just closed the gallery... and they wouldn’t agree to pay or compensate any of the freelancers for work booked. In the end they did agree… after there was a post on social media saying they don’t pay their freelancers.”

Non-disclosure agreements

Many of those we spoke to had been asked to sign NDAs or non-disparagement agreements when they were made redundant. Laura Watanabe, a partner at law firm Withers in New York, says: “It’s very typical to get an employee to sign an NDA agreement on the back end to say they cannot disclose trade secrets or take legal action… if the employer is concerned about violation.” She advises that an employee should always get adequate financial compensation in return for signing this, to not be pressured into signing and to take legal advice first.

The former employee taking action against a Los Angeles gallery says, “When I was terminated, they wanted me to sign an NDA in exchange for a very small amount of money. I did not sign it [because] I [then] wouldn’t have been able to take any [legal] action.”

Confidentiality restrictions are popular in California, where non-compete clauses (which prevent an employee working for a competitor for a period of time after leaving) are banned and the law is relatively employee-friendly, says Kim Pallen, a special counsel at Withers in San Francisco. She adds that “intense competition” between galleries is the root of most employment conflicts: “The art world is notoriously opaque…these galleries will do anything they can to protect their clients’ information.”

In the US outside California, non-compete clauses are commonly used by commercial galleries and auction houses. Those in senior positions are often banned from working for a competitor for six months or a year. In UK law, an employer does not have to pay you during the period for which you cannot work—even if you were sacked or made redundant (apart from a redundancy payment).

This, in Gorham’s view, “seems particularly harsh during the pandemic because redundancy is a no-fault dismissal… you’re out of work in a market which is gloomy and you’re subject to a non-compete.” Because of this situation, the UK government recently held a consultation (which closed on 26 February) on whether to ban non-competes or insist that employers pay some or all of a salary for the restricted period.

Can non-competes be enforced? It depends where you are—New York courts tend to side with the employer. In the UK, Gorham says that courts will not normally enforce restrictions that are too broad in scope and are longer than 12 months. But, he adds, “More often, if an employer gets wind that someone is going to join a competitor, they will get their lawyer to write a fairly aggressive cease-and-desist letter”. As for solicitation (poaching clients and colleagues), it can be hard to prove as “there’s rarely smoking-gun evidence, like an email or a text message. Most of the time its more nuanced,” Gorham says.

NDAs and non-competes are designed for senior executives, but they sometimes creep into the contracts for junior roles, either by chance or design. Julia Henderson of art recruitment agency Draw says she has come across a gallery employee earning only £25,000 a year whose future employment was hampered by a strict non-compete clause.

Junior staff may also feel greater pressure to agree to a contract they are not happy with, Watanabe says: “There’s not a level playing field between the employer and the employee, particularly in the pandemic. Junior staff don’t have the leverage to negotiate these terms to be more balanced—they’re often not fair. And that’s a problem.”