Ancient Greek sculpture

The development of Greek sculpture is intertwined with the figures painted on its vases. Just as formal, black figures gave way to more naturalistic, painted red figures, so Greek sculpture developed, between the seventh and first centuries BC, from frontal forms into more appealing, fluid pieces by later practitioners. Some names are known, including Phidias (fifth century BC) and Praxiteles (fourth century BC), but “they weren’t really considered superstar artists; they were workmen, crafting away”, says Martin Clist, the managing director of London-based specialist gallery Charles Ede.

This is a niche area of a niche category, so there are only a few dedicated Greek sculpture collectors in Europe. “The old-fashioned, connoisseur buyer has faded away over the past 15 years or so,” Clist says. “People are more seduced by beauty, and of course provenance is important.”

Antiquities has, more than other areas of the market, been dogged by problems including fakes and illicit excavation, but many of its shadier practices, which came to the fore in the 1970s and 1980s, are much improved and more stringently regulated—in the right hands.

At Tefaf, Charles Ede’s stand contains around half a dozen Greek sculptures, including a limestone Cypriot statuette of a male votary (sixth century BC, priced at £59,000) and a Hellenistic marble head of a youth (second to first century BC, £160,000).

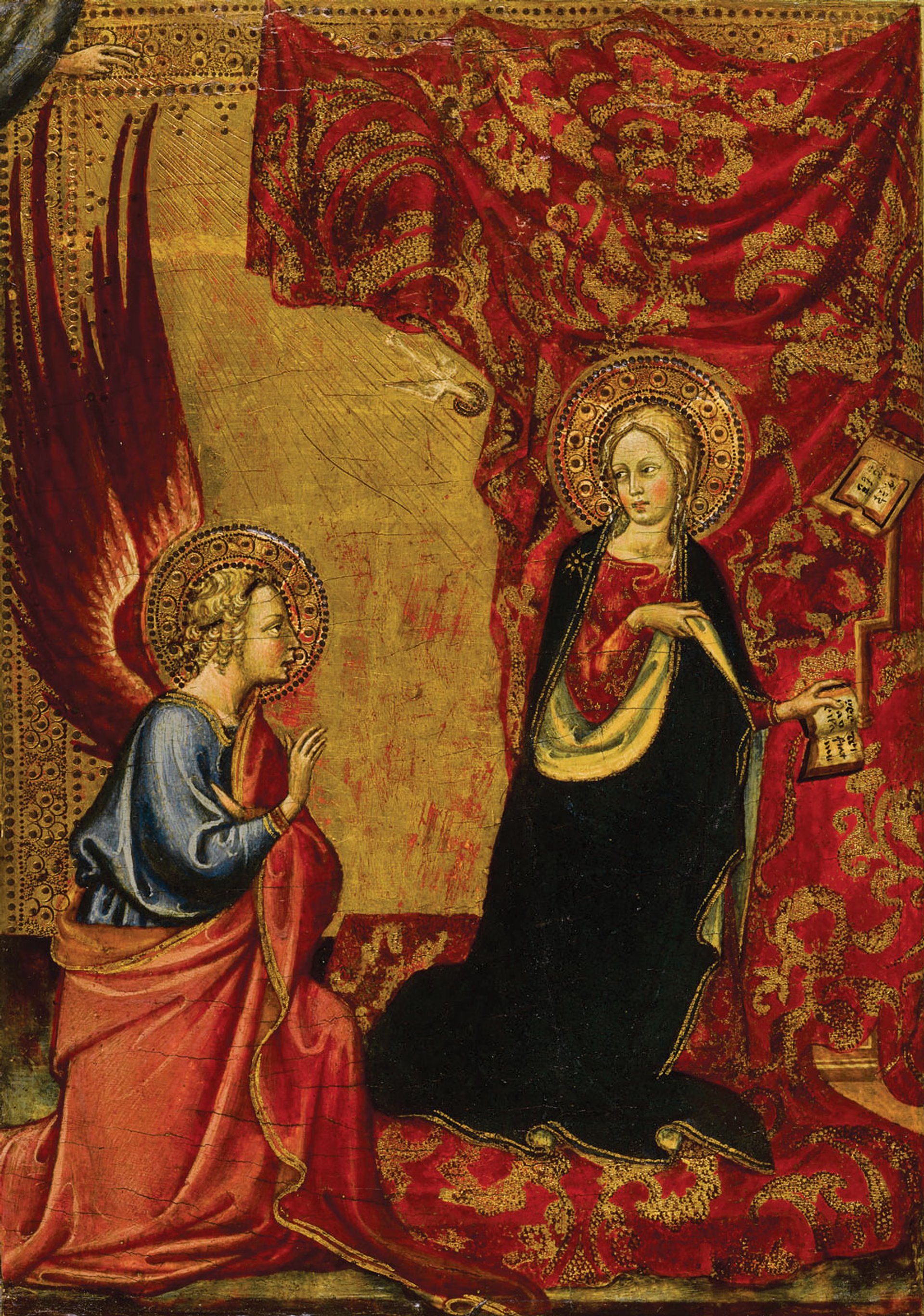

Alvaro Portoghese’s The Annunciation (1430-34) sold at Sotheby’s for $435,000 last month—a record for the artist at auction

Italian Renaissance painting

Establishing which paintings qualify as Italian Renaissance can be contentious. “Stylistically, it’s from Masaccio [born 1401] to Raphael [died 1520],” says the London-based expert Fabrizio Moretti. However, this often includes works on either side of the timeline that incorporate the increasingly humanist, sophisticated draughtsmanship and classically inspired trademarks of the official beginnings of modern Western art.

Another reason to stretch the definition is that there are very few works available. Alexander Bell, the head of Old Master paintings at Sotheby’s, describes the High Renaissance masters as “basically the [Teenage Mutant Hero] Turtles. In terms of painters, that is Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael. They have cult status.” Indeed, as Christie’s found out at the end of last year, even a debated Leonardo can attract bids of up to $400m.

Concerns about the continuing attractiveness of religious imagery can be swept aside. Bell finds that Renaissance paintings retain their historical appeal. “Collectors like the clarity; the direct, simple imagery. And when there’s a gold [back]ground, it gives richness and real impact,” he says.

Luckily, there are other artists besides the Turtles who fit the bill. Sandro Botticelli (around 1445-1510) and his studio go down well at auction; Christie’s broke records with the artist’s so-called Rockefeller Madonna (bought by the oil baron John D. Rockefeller in 1925), which went for $10.4m (with fees) in 2013. Lesser-known painters can also hit the spot. In February, Sotheby’s sold a small tempera and gold-ground panel, The Annunciation (1430-34), by Evora-born Alvaro Portoghese, for $435,000 (with fees; est $150,000-$250,000).

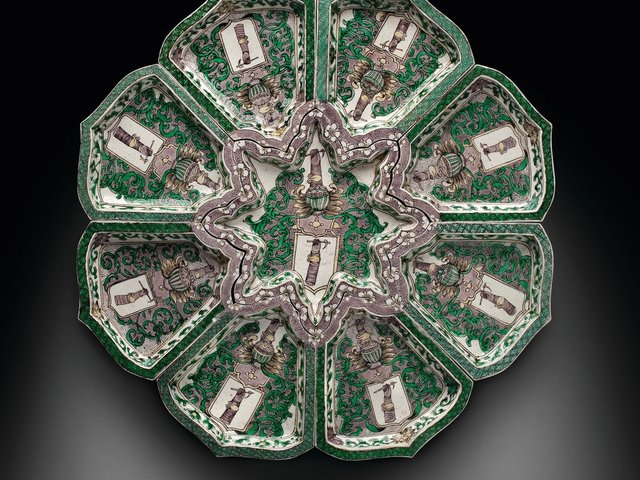

Didier Claes sold several Yaka masks (€10,000-€30,000) at Brafa, in Brussels, earlier this year

Tribal art

Generally associated with ritualistic African pieces from the late 19th to the 20th centuries, “tribal” art has come to incorporate other regions, such as the Oceanic (including Polynesia and Melanesia) and the Americas. “People no longer buy only Ivory Coast items,” says Jean Fritts, the international chairman of African and Oceanic art at Sotheby’s.

In an ideal world, pieces come from known collections: the earlier, the better, thus avoiding the cultural sensitivities associated with some tribes, such as the Hopi and other Native American communities.

Perhaps for the same reason, collectors are moving beyond masks and other fetish items into more abstract pieces. In December, a pair of Easter Island rapa (ceremonial dance blades) went for an unexpected €3.9m (with fees) at Sotheby’s, Paris. The bidder and underbidder came from other fields, representing a possible growth area for this niche market. “African art influenced Matisse and Derain,” the Brussels-based specialist Bernard de Grunne says. “The Surrealists liked the more dreamlike Oceanic pieces.”

The opening of the influential Musée du Quai Branly in Paris in 2006 has boosted understanding of the market. Other museums are upping their game, including Belgium’s Royal Museum for Central Africa, which reopens in June after five years.

African pieces still have the wow factor, particularly if presented well at attractive prices. Familiar(ish) tribes on the market include Kota and Fang (Gabon), Dogon (Mali), Luba and Yaka (Democratic Republic of the Congo). At the Brafa fair in January, the Brussels-based dealer Didier Claes swiftly sold several Yaka masks for between €10,000 and €30,000 each.

A Meissen ewer (around 1740-45) with a landscape scene, priced at £12,500 with Brian Haughton Gallery

18th-century European porcelain

A Chinese invention, porcelain began to be reproduced successfully in continental Europe, under royal patronage, in the 18th century. “Hard-paste” pieces, fired to very high temperatures, were developed at the Meissen factory in Germany, and “soft paste”—creamier in look and warmer to the touch—a little later at a factory in Vincennes, France (later relocated to Sèvres). Worcester and Bow are among the UK’s leading centres of production.

The arrival of porcelain in Europe pushed forward what Paul Crane, a specialist at Brian Haughton Gallery in London, describes as the “silver taste”. “Porcelain was used to make shapes previously made in silver, something that the aristocracy would have understood,” he says. Early, prized modellers came out of the silver trade: Johann Jacob Irminger at Meissen and Jean-Claude Chambellan Duplessis at Vincennes and Sèvres.

Private buyers often choose particular items—teapots, jugs or plates, for example—and buy deep. “Each collector finds their own pieces,” the Brussels-based specialist Jean Lemaire says.

The highest prices are often paid for items of no obvious use; fine manufacturing and provenance are more important. In 2005, Christie’s sold a pair of herons, by the Meissen sculptor-turned-modeller J.J. Kändler, for €5.6m. But prices start much lower, in the low thousands, and specialists suggest starting with tea-wares.

Lemaire thinks that the barrier to entry is more about time than money. “This is not a category for the busy. You need to go to museums, see the Sèvres pieces at the Wallace Collection, train your eyes,” he says. Questions to ask relate to restoration, later decoration and regilding, which may not be obvious.

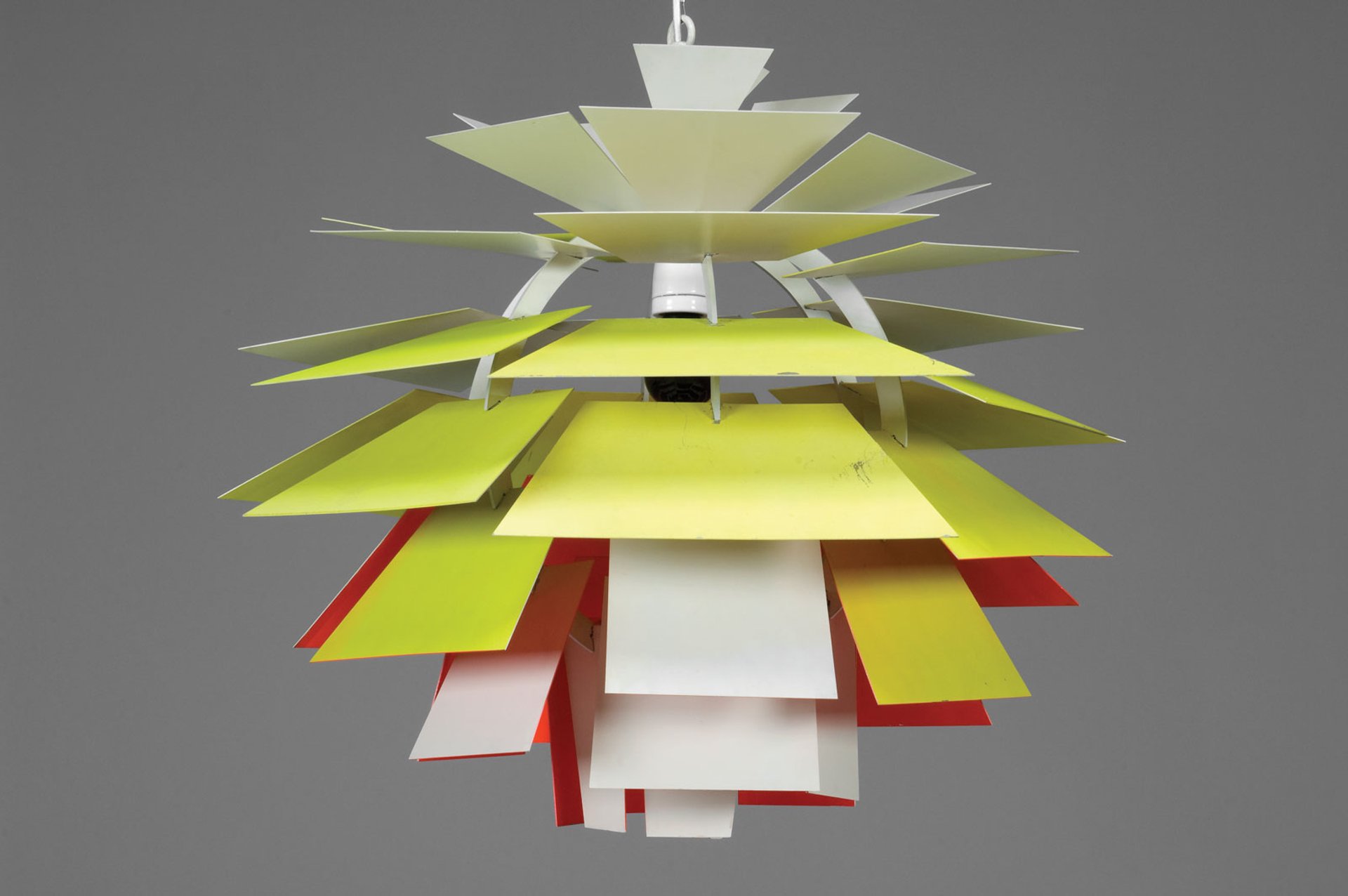

Poul Henningsen’s House of the Future lamp (1959)—one of only 15 produced—is with Jackson Design

Swedish design

Interest has been slowly building in Sweden’s 20th-century designers, particularly since the turn of the millennium, says Paul Jackson, the co-founder of Stockholm-based Jackson Design. In the process, the work has emerged from the wider Nordic design field, in which Danish and Finnish pieces are more familiar.

Alexander Payne, the worldwide head of design at Phillips, defines the Swedish style as “more regal and decorative”, with influences from France and Russia. The longstanding support of Sweden’s royal family for its architects and designers is another defining characteristic, Payne says.

Sweden boasts one of the region’s most important carpet-makers, Märta Måås-Fjetterström (known as MMF AB, also its manufacturers’ mark), founded in Stockholm in 1919. Payne describes its overarching design as “evocative and influenced by coastal water and mythology”, and highlights a hand-woven, wool MMF Tusenskönan (daisy) rug, designed in 1933 and made after 1941, that sold at Phillips in April 2017 for £47,500 (with fees).

Other specialist items coming out of Sweden include metalwork and furniture; pieces by architects-turned-designers such as Axel Einar Hjorth (1888-1959) are among the most sought-after works. Jackson has brought to Maastricht items including a Mora table by Einar Hjorth (1930, €75,000) and a Chessboard MMF carpet, designed by Barbro Nilsson (1950, priced at €25,000).

Buyers favour pieces from the 1920s and 1930s and are increasingly international. Jackson and Payne both note a rise in interest from Asia, adding to the growing excitement within the field.

This armchair (around 1765) is part of the only set of furniture made by Chippendale to Adam’s design Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 2017

18th-century English furniture

Dealers in furniture from 18th-century England face one major challenge. “There’s been a change of taste, which seems to be holding on for longer than most of us in the field expected,” says Marcus Rädecke, a specialist at Galerie Neuse in Bremen, Germany, and previously the head of European furniture at Christie’s. “People no longer aspire to the aristocratic taste.”

There are, however, knowledgeable, dedicated collectors, willing to pay high prices for the best works, which Rädecke defines as having “a good story to tell”—that is, with a strong provenance—and brand-name makers. He says a prime piece would be from a suite designed by Robert Adam (1728-92), made by Thomas Chippendale (1718-79) and owned by the Scottish businessman Lawrence Dundas (1712-81). Single chairs from Dundas’s suites go for more than £1m (the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has one), and a 1765 giltwood pair that sat in the Great Room of the businessman’s London home sold for £2.3m (with fees) at Christie’s in June 2008; Dundas had paid £20 each for them.

Collectors are still buying entry-level furniture in the £3,000 to £8,000 range, giving a glimmer of hope to dealers as the auction houses move out of this challenged category. Chippendale has become the most recognised brand, and 2018 marks 300 years since the furniture-maker’s birth, with commemorative events planned, notably in Leeds (he was born in nearby Otley). But beware: “In the US in particular, ‘Chippendale’ is used for anything that looks like it is by him,” Rädecke says.