The market for Old Masters is in a difficult place, as was clear to see on Wednesday evening when Sotheby’s could muster only £14.2m from its traditional pre-Christmas auction of paintings from before 1850. The total was less than half the £30.2m the company raised at its equivalent sale in London last December.

Geopolitical uncertainty has made owners of valuable art reluctant to sell, particularly in Brexit-blighted London barely a week before a general election. Sotheby’s, like Christie’s, which held a £24.2 million Old Masters auction the previous evening, had struggled to source high quality paintings by major names.

Or, as memorably put by James Bruce-Gardyne, an art adviser who was at Sotheby’s on Wednesday evening: “It’s Christmas dinner without the turkey. The roast potatoes are quite nice.”

Anthonis Mor, the court painter of the Spanish Netherlands, is hardly a household name, but his late 1550s head-and-shoulders portrait of the Italian medallist Jacopo da Trezzo was widely recognised as the one stand-out painting among the 39 lots at Sotheby’s.

Anthonis Mor, Portrait of Jacopo da Trezzo (late 1550s) Image courtesy of Sotheby's

Notable for its immediacy, humanity, technical quality and fine condition, Mor’s two-foot-high panel depicting a fellow craftsman in the Spanish Empire was pursued by five bidders to £1.9m with fees, an auction record for the Utrecht-born artist. It had been estimated to sell for £300,000 to £500,000.

The free-spending private buyer of the Mor, bidding on the phone, bought three further lots, including a large and extensively restored 13ft-wide canvas of Diana and her Nymphs Hunting (around 1636) from the studio of Peter Paul Rubens. This surprised dealers in the room when it sold for £1.7m, more than three times the upper estimate. “It’s studio, but good studio. The brand works,” says David Jaffe, a former senior curator at the National Gallery in London, referring to the continuing allure of Rubens as a name.

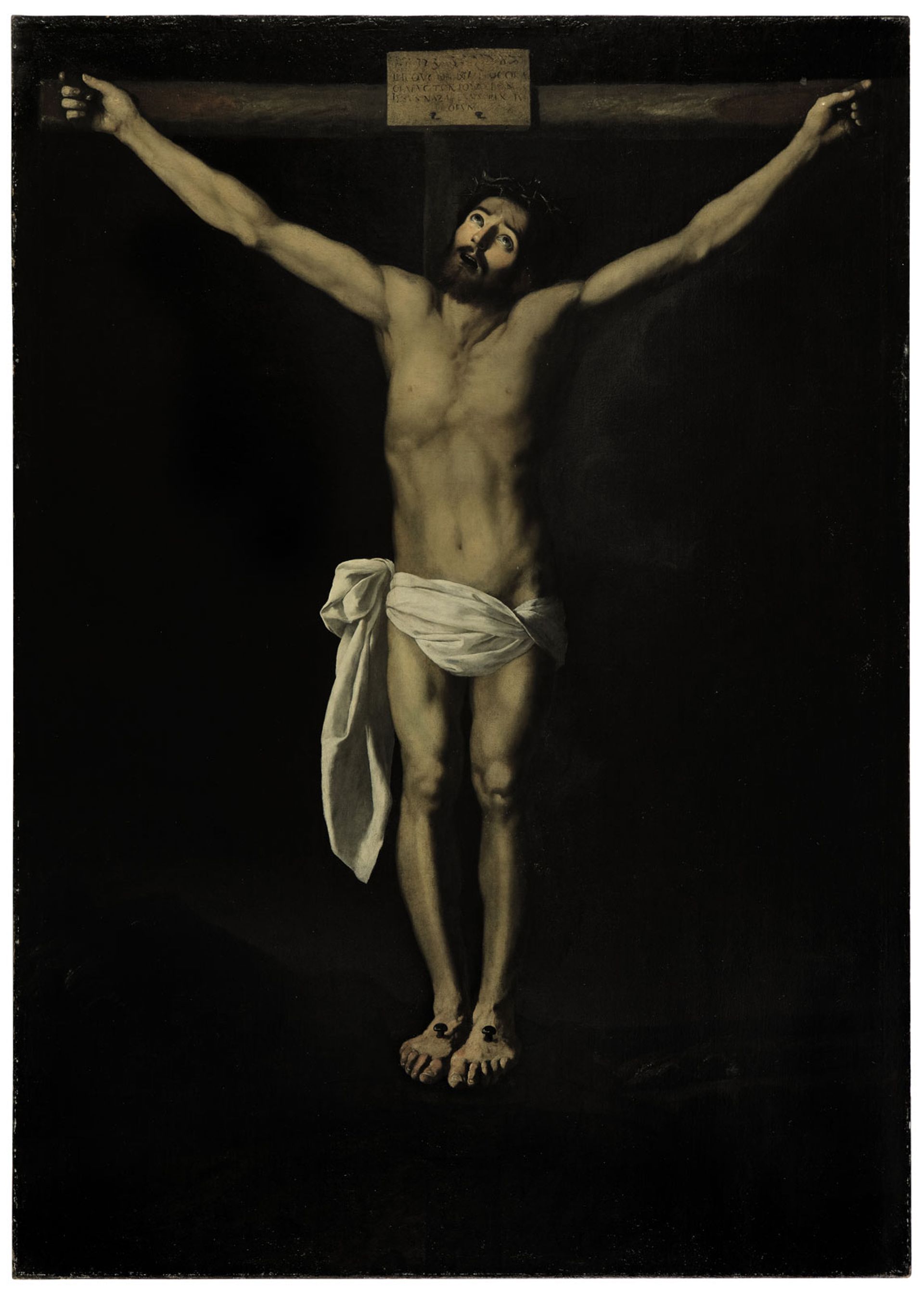

Francisco de Zubarán's Christ on the Cross (around 1635) failed to sell, despite not having been seen recently on the market Courtesy of Sotheby's

Nicolas Poussin and Francisco de Zurbarán are also pretty major names, but paintings by these two 17th-century artists, whose sellers had both been guaranteed minimum prices by Sotheby’s, failed to generate excitement.

Though a small 1648 Baptism on cypress panel was unusually well-documented in Poussin’s correspondence, the artist (as he admitted in a letter) was not at ease on this scale. The painting sold to a phone bidder for £1.8m (est £1.5-2m). There were no takers for an intimidatingly large and lugubrious Zurbarán Christ on the Cross (around 1635) painted for the South American market. A failed house guarantee of about £2.5m would have an unwelcome dent in the profit line at a time when Sotheby’s is adjusting to new private ownership.

Both paintings—like the record-breaking Mor portrait—were among the 70% of lots in the auction that had not been recently seen on the market, according to Alex Bell, Sotheby’s worldwide co-chairman . “We try to keep the sale as commercial as possible,” Bell says. “Buyers like a sense of discovery.”

The difficulty for Old Masters is that the supply of fresh material is finite and ever-diminishing. Sotheby’s, like Christie’s, has a reliable clientele of wealthy private clients willing to buy attractive paintings that have been unseen by the market. But what happens to paintings that have been through the commercial mill?

More often than not, they sell for a loss, if at all. Here at Sotheby’s, for instance, a Luca Carlevarijs view of the Grand Canal in Venice (around 1720s) was knocked down for a hammer price of £110,000, before fees (which is what the seller cares about at this level). It had been bought at auction in 2003 for £229,600, including buyer’s premium. A signed and dated 1624 Johannes Bosschaert still life of flowers in a basket was hammered at £150,000, less than half the £375,000 auction purchase price in 1995. An early 17th-century landscape by Sebastiaen Vrancx showing marauders hijacking a wagon, bought at auction for $135,000 in 1994, was among nine lots that failed to sell. It had a low estimate of £100,000. These are the sort of paintings that used to be routinely bought for stock by Old Master dealers preparing for the Tefaf fair in Maastricht in March.

“For dealers like us, it’s difficult,” says Luigi Caretto, an Old Master dealer based in Turin. “The medium and low quality is impossible. It’s just the good paintings that get results, and there are lots of private clients here.”

The auction houses, with their international marketing machines, now dominate what remains of the trade in Old Masters. For everyone else, selling old art is tough going.