The International Monetary Fund issued a stark warning last month: the global economy has almost certainly entered a recession the likes of which was only seen during The Great Depression of the 1930s. As industries lie dormant, quarantined by the coronavirus (Covid-19), global output could contract by 3% in 2020, the IMF says.

But, economics is not a precise science. As Paul Donovan, the chief economist at UBS Wealth Management, says: “the data is currently non-existent”. He believes we will not know until late 2022 what is actually happening now but, he says, “a good rule of thumb is that every month of lockdown will cut a country’s GDP by 2% to 3% each month”.

It is the same story in the notoriously opaque art market: reliable data is hard to come by at the best of times. With the vast majority of bellwether public auctions postponed (lower-value sales have migrated online), taking the temperature of a trade that has all but disappeared is harder than ever.

Dealers and other experts grappling with our rapidly evolving situation are looking to the global financial crisis of 2008 as well as 9/11 for clues. Yet, as the cultural economist Clare McAndrew says: “The death toll in New York itself has already surpassed 9/11, and that was an event in one city, albeit with global implications. There is simply no comparison to the economic severity and global nature of this current crisis.”

Worse than 2008 crash?

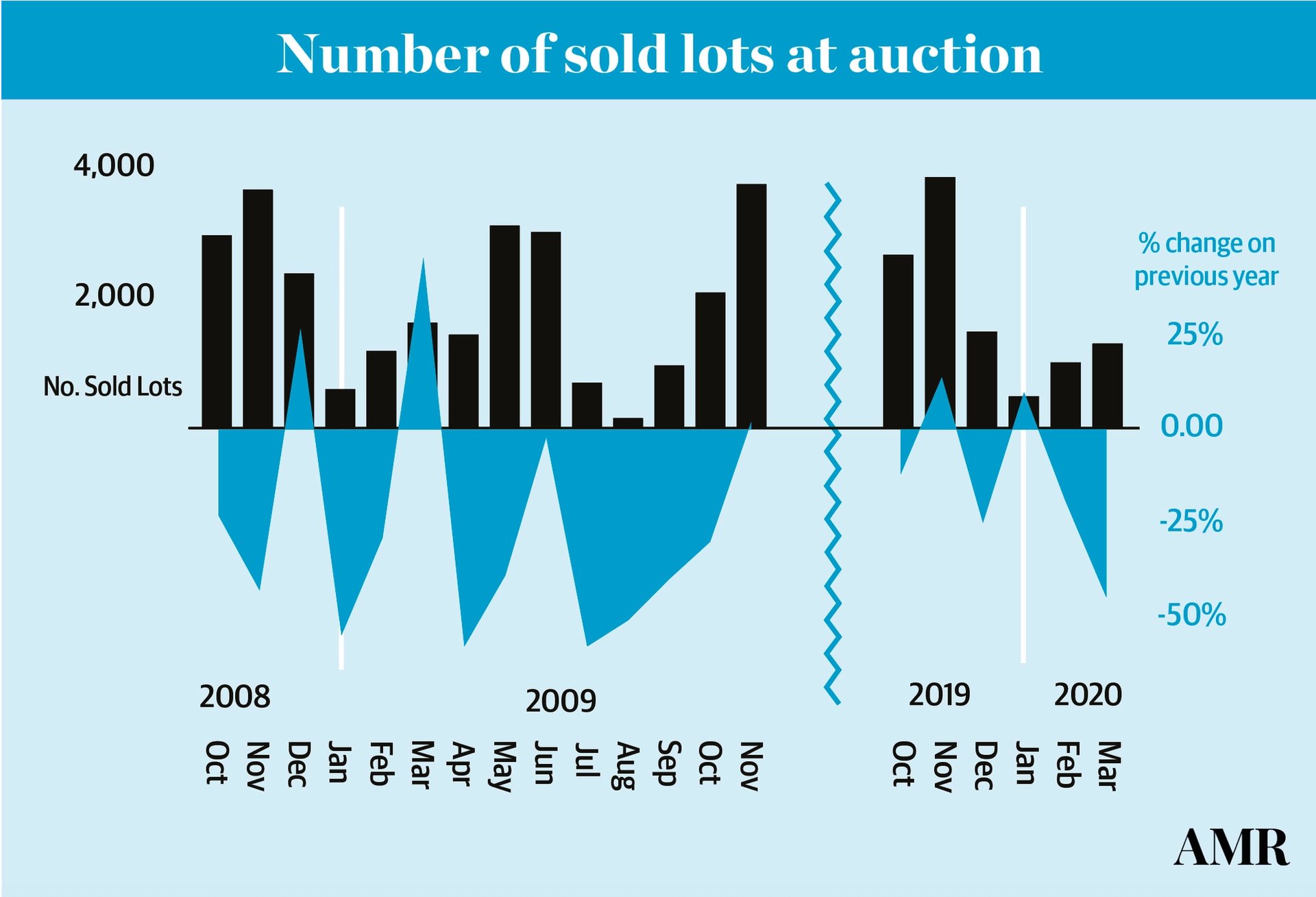

Early figures suggest the art market could be on course for a similar crash to 2008/09, if not worse. According to data compiled by Art Market Research (AMR), in March 2020 (see graph below) there was a 45% drop in the number of fine art lots sold at auction compared with the same month in 2019—not altogether unsurprising given the unprecedented closure of auction houses. More than half of March’s 80 fine art sales have been postponed.

That drop almost exactly mirrors the 43% dive in sales recorded in November 2008, the first real public test of the market after Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy two months earlier. The biggest plunge—59%—came in July 2009.

Supply may be down but (some) demand is still there. “Collectors haven’t deserted the market in huge numbers yet,” says AMR’s managing director Sebastian Duthy. “Of course, it took several months before the impact of the 2008 crisis was fully realised in terms of drop in sales, so we shall have to wait and see how consigners respond to this crisis.” He notes that some smaller auctions have done well online, including Sotheby’s 20th-century design sale in March, which brought in $4m—more than 25% above its high estimate. Now that we are cooped up at home, interior decoration has perhaps never felt so vital.

Anecdotally, dealers are doing a limited amount of trade on the private market, most of it primary sales. Speaking on a Zoom webinar last month, Brett Gorvy, the co-founder of Lévy Gorvy gallery and former Christie’s chairman, says prices are hard to gauge at the top of the market but, based on fair market value, prices for blue-chip post-war artists have come down to 2015 low estimate auction levels. “Buyers, if there are any, are expecting a 35% to 40% discount. At the moment we’re seeing more of a scavenger mentality,” he says.

Gorvy attributes this to prices being more “controlled” than in 2008 when the art market was particularly frothy. In the contemporary art sector alone, prices rose 313% in the two years to September 2008 culminating in Damien Hirst’s two-day sale at Sotheby’s, which made a blockbusting £111.4m. Not so this time, Gorvy says, noting the “correction” of 2016. “The art market hasn’t been as leveraged as it was in 2008. So we’re not seeing distressed selling,” he says.

Toxic debt held by banks was one of the biggest factors of the 2008 crash. Today, financial institutions are far more resilient, McAndrew says: “Banks went into this crisis much stronger than before the global financial crisis and have been amassing capital and liquidity buffers to deal with a possible recession for the past decade.”

However, the IMF warns that current stresses could expose fault lines in the financial industry, in particular high levels of corporate indebtedness, while others believe markets were already heading for a fall.

Compounding the current situation is the fact that it will also be the second major recession in just over a decade, “which is unprecedented”, McAndrew points out. The effect of a second recession in such a short space will be critical for the art market. As McAndrew says: “Many businesses were only starting to do well again in the last few years. There’s barely any credit and lending in the gallery sector; businesses are already heavily burdened with rents and other costs, so many don’t have any spare funds to ride it out.”

AMR’s data shows the number of lots sold fell by 45% in March compared to March 2019 © Katherine Hardy. Data courtesy of Art Market Research

Prioritise small businesses

As in 2008, governments around the world are now weighing multi-billion, if not multi-trillion-dollar bailouts—measures that have seen the stock market rally after a plunge on 23 March wiped out almost $10 trillion. The crucial question is how the stimulus package will be distributed to individuals and smaller businesses rather than swelling the reserves of banks and corporations as happened in 2008, sparking furious backlash on both sides of the Atlantic.

Donovan believes the banking sector must now work with governments to ensure small businesses survive, “either by transmitting government funds very quickly or by providing temporary lending until funds can come through”. He adds: “Every week that it’s delayed, small businesses in particular become extremely vulnerable.” Some think tanks are calling for certain conditions to be attached to corporate bailouts including job security and, in the case of the aviation industry, climate justice.

For many galleries and smaller art firms who are struggling to pay their rent and bills, short-term aid will be make-or-break. Furlough schemes, which helped countries including Germany weather the 2008 crisis, should ease other overheads, Donovan says, while crucially keeping already bloated unemployment from spiralling further.

As the US and Europe continue to fight with the underlying pandemic, Asia could offer a glimmer of hope; dealers and auction houses say business is tentatively picking up again in the region as countries emerge from quarantine. “Markets have always moved from centre to centre. New York has been the centre for so long. Where is the new centre going to be? Could it be here, online?” Gorvy ponders.

For now, at least, the axis of power is leaning to the East—might Chinese buyers boost the art market’s recovery, as they did in 2010 when the Chinese art market was booming despite the global financial crisis? Since then, the trade in China has had a “considerable shakeout, including some dubious and very speculative practices”, McAndrew points out. She is still “very optimistic” about sales in China in the longer term, but thinks there will not be the same sharp uplift as in 2010 as “even if demand were to come back strong, there are still supply issues across the market”. What is more, chasing art as an asset class, an idea that gained traction globally after the last crisis, could—in the short term at least—be seen as inappropriate.

Lingering hopes that the global economy will make a swift V-shaped recovery once lockdowns are lifted are also dwindling. As McAndrew says: “Initial hopes that this would be a short-term crisis and things would kick back into action with pent-up demand stimulating art sales now seem less likely.” Even with global economic growth predicted to rise to 5.8% in 2021, analysts say a U-shaped recovery, with a drawn-out bottom, is the most probable outcome as we adapt to a socially distanced life outside of quarantine. As Asian countries are threatened with a second wave of coronavirus, others anticipate a grimmer double dip or W-shaped return.

What is certain is that this crisis has prompted an economic reset. It has raised long-term questions about unfairness and inequality, which are trickling down to the historically indifferent art market. The question, then, is not what form recovery will take, but what form our industry will take when it emerges blinking into the light.