The contemporary art market yo-yos with the stock markets and whims of speculators, the auction results of its young stars shoehorned into indexes that dress them up as investment material.

But Old Masters are a more capricious beast. This is not a constructible market with a continuous supply from malleable young artists; instead, there are fallow years, offering only dull landscapes filled with depressed cattle, and ropey boss-eyed portraits, when dealers will tell you (from their second homes in Provence) that the end is nigh and supply has dried up once and for all.

But then out of the blue there will be a little glut, of kitchen Cimabues or barn-find Caravaggios (turned up by the Paris-based expert Eric Turquin), or gems on the walls of an unremarkable London house—remember Rubens’ Lot and his Daughters sold at Christie’s in 2016 for £44.8m.

Or, more recently, $80m Botticelli portraits released from the collections of recently deceased tax-savvy billionaires.

The Wine Harvest by David Teniers the Younger Courtesy of Sotheby’s

Being nimble

This year has presented the Old Master market with another challenge—the pandemic has forced this resolutely analogue trade to go digital, like everyone else. But it faced more hurdles in doing so than the digitally native contemporary market, largely due to an older clientele and issues of condition and authenticity that make in-person viewing of works far preferable.

As Andrew Fletcher, Sotheby’s head of department, Old Master Paintings, says: “Never have we learned so much about what we can do in such a short space of time. We had to be so nimble.” Two weeks into lockdown in March, Sotheby’s held a sale of the collection of the London dealer Rafael Valls, which was quickly converted from live to online auction, and made £1.6m—four times its estimate. “Clearly people had a lot of time to look at art, and the number of buyers and visitors we had for that sale was off the charts,” Fletcher says. Sotheby’s swiftly held the sale of the collection/stock of another London dealer, Danny Katz, which made £2.3m in May.

Mixing an Old Master evening sale with contemporary works, as in Sotheby’s live-streamed Rembrandt to Richter auction in July, has always been an aim of Fletcher and his Sotheby’s colleague Alex Bell. “So we thought, if we can’t do it now, we’ll never do it,” Fletcher says. All 12 of the Old Masters in the sale sold, and the sale “put Old Masters on a stage that we’re not normally on in terms of publicity and collectors—we had multiple new bidders from the contemporary and Impressionist world”.

Karl Hermanns, the global managing director of Christie’s Classic Art Group, concurs: “Lockdowns have accelerated digital strategy, both in terms of marketing and selling online. Old Masters have been as active in this space as any—our first online Old Master sale in New York in June totalled just under $3m but, most importantly for future growth here, 22% of the buyers were new, and 52% were making their first online purchase with us.”

Hermanns adds that in the July online-only auction Remastered, a collaboration between Old Masters and post-war art, Pieter Brueghel the Younger’s Adoration of the Magi sold for £551,250—double its estimate. “Few would have predicted a year ago that an Old Master painting could sell for half a million pounds in an online-only auction.”

New digital tools have helped—Christie’s has introduced super-zoom photography and augmented reality to enable clients to “view” works in their home. “The use of Google Street View-style, 360-degree virtual walkthroughs, virtually hung galleries, as well as lower-tech Zoom videos on specialists’ iPhones, have been able to get clients as close as possible to the art in situ,” Hermanns says.

Increasing numbers of buyers are buying sight-unseen—normally a no-no in the Old Masters field. And it even happens at the top end of the market—in Sotheby’s Rembrandt to Richter sale, “some high-value works sold sight-unseen”, Fletcher says. “Collector confidence in buying unseen has grown immeasurably in the past nine months—normally that confidence would have taken three years or so to build.” Sotheby’s hasn’t yet had an instance of a collector being unhappy with an Old Master work bought remotely, he says.

Forging relationships with new buyers online, however, is more difficult, Fletcher concedes. “They’re getting so much more information without having to contact a specialist. A lot of our job before was sending information out to people—pictures of the back of the painting, of the frame, etc. That has now been taken over by our system, so that sort of contact has dissipated.”

However, with existing clients, he has been using video calls a lot: “I can show them the painting in raking light to see the surface on my phone. It has made communication about the picture a lot easier.”

Georges de La Tour’s A Girl Blowing on a Brazier (La Fillette au Braisier) Courtesy of Lempertz

Working together

Of course, while it is all very well for major auction houses with big digital teams to use sophisticated virtual tools, Old Master dealers and galleries do not have such technology at their disposal. But one thing they can do is collaborate—the winter edition of London Art Week (LAW), for instance, is taking place online (until 11 December), providing an online viewing platform for more than 50 dealers (and a few auction houses), supplemented by a talks programme.

“Most of my clients are fairly used to looking at things online, though they’d prefer to see them in real life,” says LAW’s chairman and works on paper dealer Stephen Ongpin. “What reassures me is that most of them are true collectors—they’re not buying for investment or status. Those clients are most likely to come back.”

Old Master collectors “tend to be passionately invested in the market”. Ongpin adds: “If I were a young, cool gallerist in Hoxton dealing in cutting-edge contemporary art, I’d be really nervous—it’s a difficult model to maintain in this environment.”

Ongpin plans to venture over to New York in January for Master Drawings New York, where he will hold an exhibition by appointment only. “New York in January has been very successful for us over the past ten to 15 years, and I’d hate to lose that. I still think it’s worth renting a gallery. I understand there won’t be many people coming from overseas, or from the West Coast, but there will still be enough people able to come.” It helps that Ongpin and his staff are American, so are still able to travel to the US. He adds: “If we don’t do a show in New York in January, then the next thing is Tefaf Maastricht, which is now delayed until the end of May.” Having Frieze Masters, the Salon du Dessin, the Draw art fair and Tefaf New York Fall cancelled this year has hit Ongpin’s revenue “a lot; the bulk of my business is done at fairs”.

Anthony Crichton-Stuart, the director of Agnews, another LAW participant, says business has been “sporadic”, although as many of his clients have been so bored, there is still an appetite to buy. His operating costs, without fairs, have been dramatically reduced, too—“doing all those fairs was like having another gallery”.

Crichton-Stuart foresees “a lot of attrition in the fairs market—galleries are really going to tighten up”. As for buying works blind, Crichton-Stuart says he is happier to do so with 19th- and 20th-century works than older pieces: “They are easier to judge; there are fewer subtleties than with older works.” He also finds it harder to “get a sense of a sale online, without a printed catalogue. It’s harder to concentrate—you almost want there to be nothing, so you scroll faster than you should—it’s easy to miss things.”

This is, Crichton-Stuart thinks, a time to “reflect on how we do business”. The Old Master trade has “to change it up a bit, broaden our reach. I thought that beforehand, but now it’s even more pressing—we have to be more interesting, more accessible.”

Crichton-Stuart adds that a positive to come out of the pandemic has been a new collegiality among the art trade. While dealers once saw auction houses as, frankly, the enemy, in lieu of fairs the past year has seen an unprecedented number of auctions of antiques and Old Master dealers’ stock and collections through Christie’s and Sotheby’s. It’s a mutually beneficial arrangement—the dealers benefit from the auction houses’ superior marketing reach and digital infrastructure in order to shift some stock, while in return the auction houses get a ready supply of material to feed a punishing sales schedule.

“We are doing what we can to support one another—it is a really challenging moment for the market—but essentially, yes, auction houses are providing an outlet or platform for dealers at a time when they are not able to exhibit at international fairs, and we are looking for creative ways to collaborate with the trade [so] we can all benefit,” Hermanns says.

Until 14 December, Christie’s is hosting a sale titled Professor, Dealer, Collector, of Manuscript paintings from the well-known, New York-based medieval manuscripts dealer Sandra Hindman. Eugenio Donadoni, the senior specialist and head of sale, says, ‘‘This is the first time that Christie’s has collaborated on a single-owner auction with a pre-eminent dealer in medieval manuscripts.” He adds, “Adopting a collaborative rather than a competitive approach with dealers allows us to broaden our scope.”

Fletcher is upbeat: “Actually looking at the results this year, it’s a very strong market and a lot of consignors have put their trust in that market.”

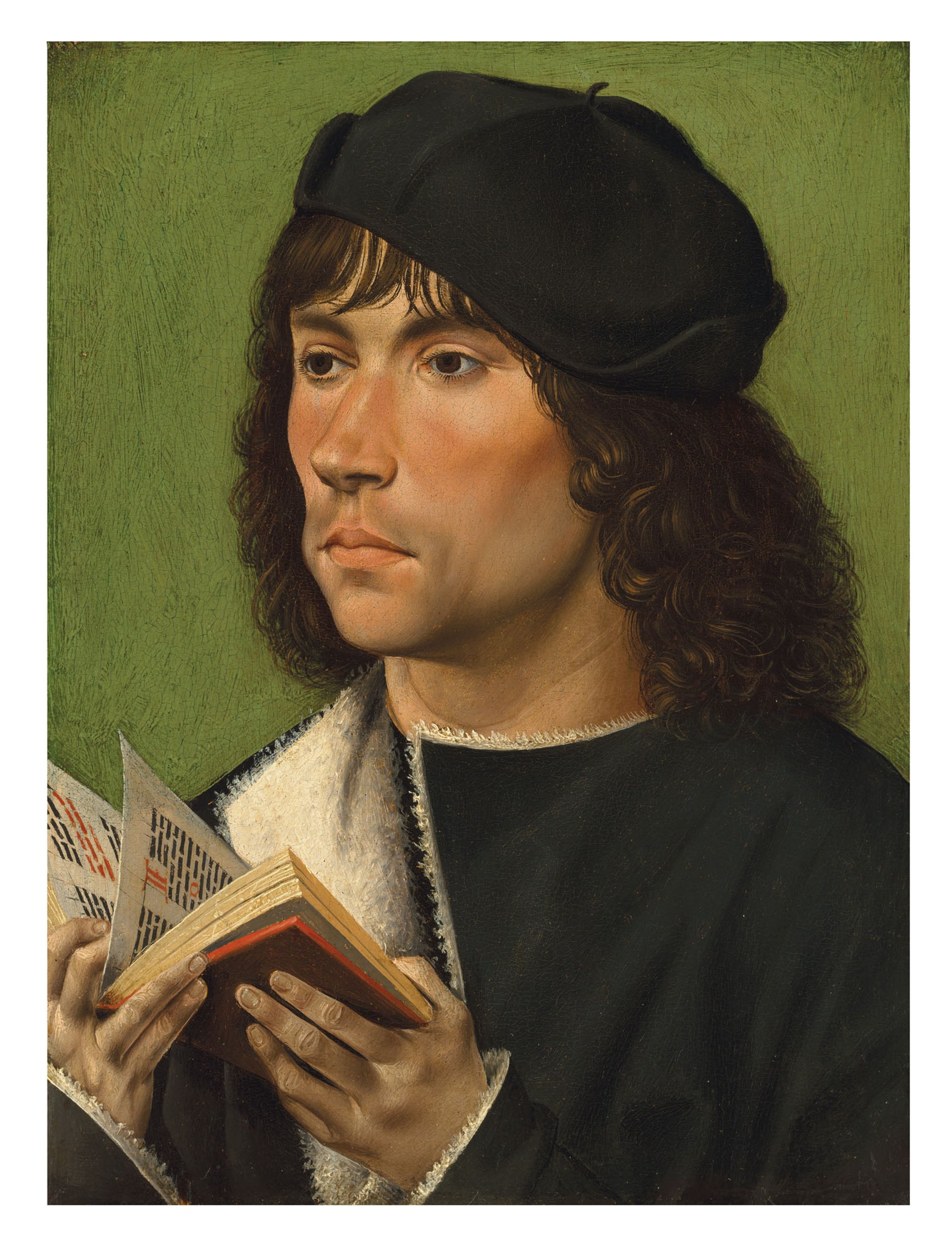

Burgundian Master (around 1480), Portrait of a Man Holding a Prayer Book, sold by Christie’s in July for £1.6m Courtesy of Christie’s

Trends

It’s difficult to talk about specific trends in the Old Master world, aside from the age-old adage that good-quality, fresh and rare works will always be in demand.

Clementine Sinclair, Christie’s head of sale, Old Masters Evening Sale in London, sees a rising interest in female artists, notably Artemisia Gentileschi (her Triumph of Galatea sold for $2.2m in October), and certain schools, “for example, early Netherlandish”, such as the exceptional Burgundian School’s Portrait of a Man Holding a Prayer Book, which sold in July for £1.6m.

Demand for Venetian vedute scenes has, however, softened. Sinclair also notes a demand for works by Lucas Cranach and Rubens—the latter’s Portrait of a Young Woman (1603-06) sold at Christie’s in July for £3.9m, under a £4m to £6m estimate, going to the guarantor. Third-party guarantees have, according to Hermanns, “become a valuable tool for our seller and buyer clients in Old Masters as they have been in 20th-century art”.

Hermanns adds that collections showing a clear individuality of taste also perform well, pointing to Christie’s sale of the Robert Landolt collection of Italian Old Master drawings, which totalled £1.6m on 8 December, and “Dutch Golden Age works in the Michael Feldstein auction in New York in October”.

Go back 20 years and Dutch Golden Age works were pre-eminent on the Old Master market—take the prime stands at the entrance of Tefaf Maastricht, where dealers such as Johnny van Haeften, David Koetser, Richard Green et al held court with heavy-framed still lifes, marines and windswept landscapes. This has dwindled over the past decade—van Haeften, for instance, no longer takes a stand at Maastricht and has given up his gallery—and these Dutch works have slipped slightly from fashion. But over the past 12 to 18 months, Fletcher has seen an “encouraging” return to the Golden Age, previously the mainstay of any Old Master sale. “This is where a lot of new collectors are coming in—into van Goyen and van Ruisdael and artists like that,” Fletcher says.

Fortunately, there is also a lot of Dutch Golden Age material around, so when that market comes back, “it’s huge. Whereas early Netherlandish pictures are hugely popular but almost impossible to find—you can’t build a sale around a core of them because they don’t exist,” Fletcher says. Italian and Flemish Renaissance pictures are, Fletcher adds, “on everyone’s shopping list at the moment”.

Salaì’s Penitent Magdalene sold for €1.7m © Artcurial

Recent highlights

The past few weeks have offered up a couple of gems in European salerooms. On 8 December, the German auction house Lempertz sold Georges de la Tour’s atmospheric A Girl Blowing on a Brazier (1646-48) for a record €3.6m (€4.3m with fees)—the most expensive Old Master ever sold at a German auction house. La Tour’s paintings are exceptionally rare on the market—this was the first to come up for auction since 2008, and it had been bought in 1975 by the late German airline owner Hinrich Bischoff for £17,850.

Last month at the Paris auction house Artcurial, a painting of Mary Magdalene recently attributed to Leonardo da Vinci’s collaborator and lover, Gian Giacomo Caprotti, known as Salaì, sold to an American collector for a record €1.7m ($2m, with fees). The oil on panel, dating from around 1515-20, and previously thought to be by Giampietrino, was estimated at €100,000 to €150,000. As Ongpin says, “It wasn’t a great picture, but it’s art historically interesting, and we know a lot about Salaí. And the auction house immediately sent out a video of the auction, which helped to bring it to life, even though these empty auction rooms are a little strange.”

Jan Davidsz de Heem’s A banquet still life (est. £4m-£6m) Courtesy of Christie’s

Coming up

Tonight, Sotheby’s Old Master evening sale includes David Teniers the Younger’s 17th-century enormous painting, The Wine Harvest, which has been hanging over the mantelpiece in the Long Gallery at Firle Place in Sussex for many years. It was bought, probably in the 1770s, by Peniston Lamb, 1st Viscount Melbourne, who hung it at Brocket Hall, and was last shown in public in 1881 at the Royal Academy of Arts. It is now estimated to sell for £3m to £5m.

Meanwhile at Christie’s evening sale on 15 December (est. £17.2m to £26.2m), the star lot is another enormous canvas, this time a still life (in filthy “country house” condition) by Dutch Golden Age painter Jan Davidsz de Heem, which is billed by Christie’s as “one of the finest still lifes to come onto the market this generation” and estimated at £4m to £6m.

These mid-season London sales are somewhat overshadowed by those next month in New York. Sotheby’s has its highest-value Old Master evening sale ever on 28 January, with the top lot being that $80m+ Botticelli portrait and co-starring Rembrandt’s Abraham and the Angels (1646), which was last sold at auction for £64 in 1848. Consigned by Mark Fisch, a major collector and trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it is now estimated to make $20m to $30m.

Sotheby’s is also selling the collection of the late New York collector, interior designer and philanthropist Hester Diamond. A woman of daring and playful taste, Diamond’s High Renaissance Italian and Spanish works hung in her extraordinary home alongside luminous pink chairs and minerals. Top lot is a sculpture by Gian Lorenzo Bernini and his father Pietro, titled Autumn (1616), estimated at $8m to $12m.