1931

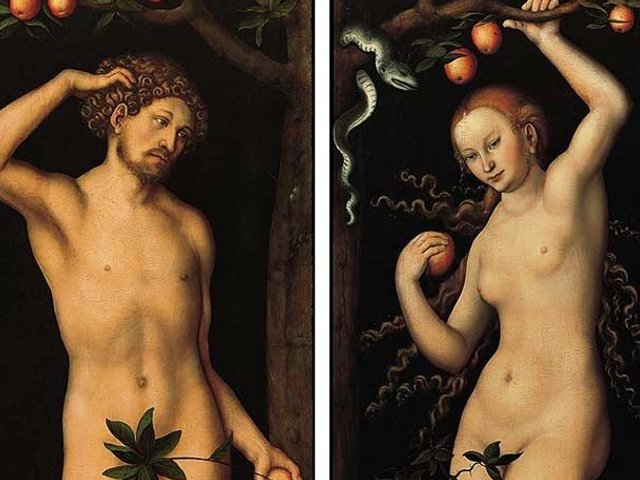

The Jewish collector and dealer Jacques Goudstikker buys the pair of paintings Adam and Eve (around 1530) by Lucas Cranach the Elder at an auction in Berlin of works “from the Stroganoff Collection”.

1940

Goudstikker flees the Nazi-invaded Netherlands, dying en-route. His collection is seized by Hermann Göring, Hitler’s deputy. Although much of it was returned by the Allies to the Dutch authorities for restitution in 1946, his heir and daughter-in-law, Marei von Saher says the art, including the Cranachs, was not returned to the Goudstikker family.

1961

The exiled Russian aristocrat George Stroganoff-Sherbatoff claims that he is the rightful owner of four paintings in Dutch hands—the Cranachs, a Rembrandt and a Petrus Christus—which he said had been seized by the Soviets after the Russian Revolution.

1966

The Dutch government sells the Cranachs to Stroganoff-Sherbatoff for 60,000 guilders.

1971

The American collector Norton Simon buys the Cranachs from Stroganoff-Sherbatoff for $800,000. The Pasadena Museum of Modern Art was renamed for Simon in 1975.

1990s

Von Saher initates a claim against the Dutch government, but this is rejected by the Dutch courts on the grounds that her family had relinquished its rights after the war.

2006

The Dutch government returns an important group of 202 paintings in its possession from Goudstikker’s collection to von Saher, many of which are then sold at Christie’s New York on 19 April that year.

2007

Von Saher sues the Norton Simon Museum for ownership of the Cranachs. The museum files a counterclaim, saying that it had legal title to the paintings. The museum says the paintings were once part of the Stroganoff collection that the Soviet government seized after the Russian Revolution of 1917, and that the Dutch government precluded any Goudstikker claim in 1966 when it returned the paintings to an heir of the Stroganoff family.

Von Saher says the Cranach paintings, were not “and had never been” part of the Stroganoff collection.

The Norton Simon foundation argues that title to the work passed out of the Goudstikker family’s hands when the Dutch government restituted them in 1966 to Stroganoff-Sherbatoff and that it therefore acquired lawful title when it bought the works from him. It also argues that a US court may not invalidate the Dutch government’s decision, which was an “act of state” of a sovereign government.

2015

Norton Simon Art Museum, together with the Norton Simon Art Foundation, files a motion with the California District Court to dismiss von Saher’s claim.

It argues that the statute of limitations expired “some time in the 1950s”, according to the court papers.

California’s district court denies the motion to dismiss the case, finding that: “the fact that the statute of limitations may have expired as to an owner’s claim against the thief (or prior possessor) is irrelevant”.

2016

US District Court in California dismisses von Saher’s claim. It rules that the paintings became the property of the Dutch government after the Second World War.

Von Saher’s lawyer, Larry Kaye, says this client was disappointed by the decision but “remains undaunted and is optimistic that she will prevail in the end”, and she plans to file an appeal.

2018

A federal appeals court upholds the earlier ruling in the museum’s favour, arguing that the issue had been decided by the Dutch authorities. The procedure of “state doctrine” means that it had no power to invalidate the Dutch government’s decisions. Lawrence Kaye, von Saher’s lawyer, said she was disappointed and “considering her next steps”.