We returned to our palaces, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With alien people clutching their gods.

The closing sequence of T.S. Eliot’s 1927 poem, Journey of the Magi, in which one of the three kings recalls in old age the disillusion he felt on his return after the “hard and bitter agony” of a journey to witness a birth “like Death, our death” is a prescient metaphor for our coronavirus-darkened times. If and when the pandemic abates, will societies reset and reform? Or will they return to the “old dispensation”?

Such questions could equally be asked of the $60bn god-clutching art industry, one of the many sectors devastated by the pandemic.

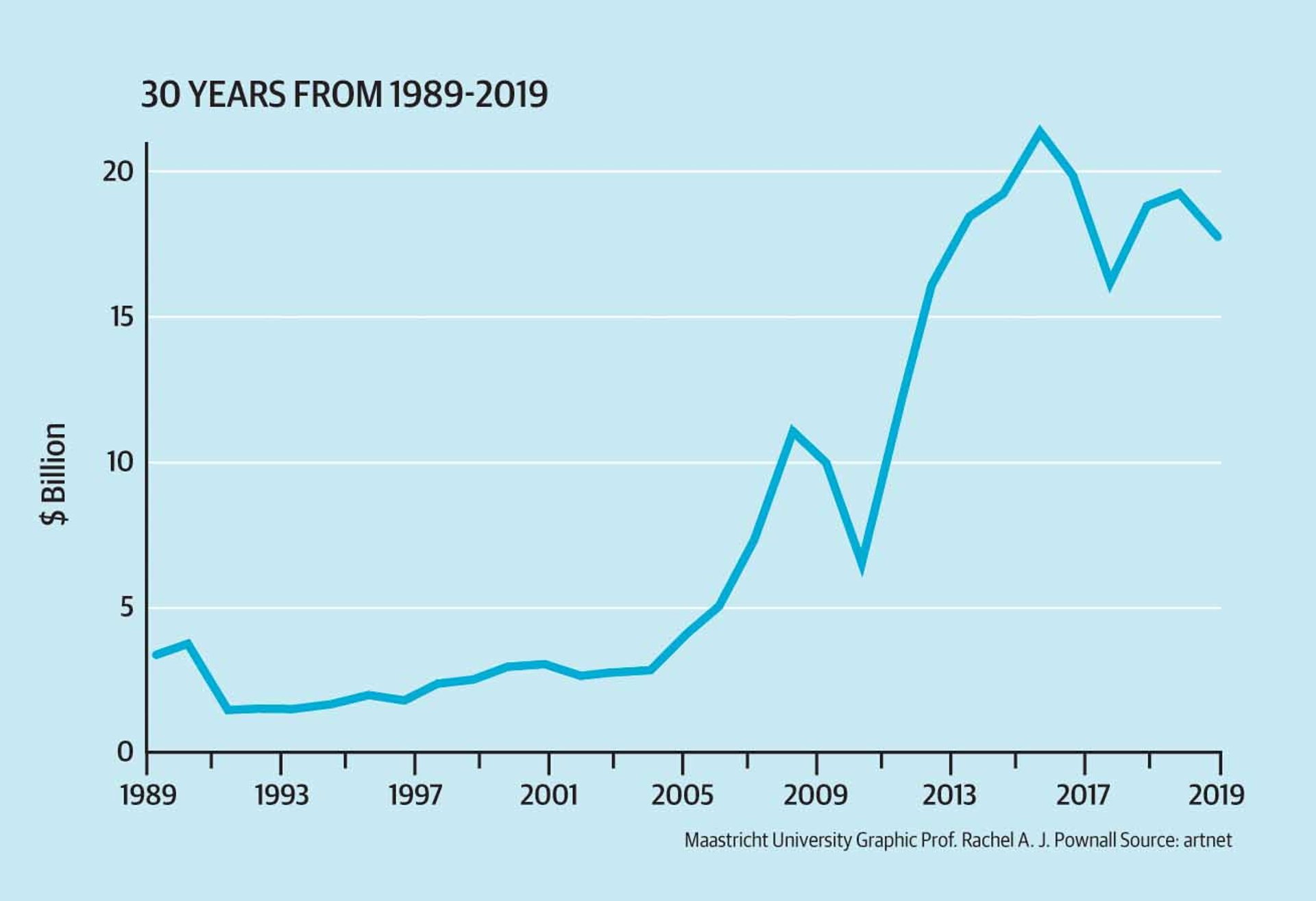

It is too early to predict how this crisis will affect the art market in the long-term, but previous slumps provide some clues. Rachel Pownall of Maastricht University has compiled the annual totals of the past 30 years of auction sales (the market’s only reliable data), during which two significant downturns occurred, in 1991 and 2009.

Back in 1991, the auction market shrank by a staggering 62% as Japan’s asset price bubble collapsed and with it the market for multimillion-dollar works by Renoir and Van Gogh. Sales took 13 years to recover to their 1990 level.

In 2009, as a result of the banking crisis, auction sales fell by a less calamitous 36%. The following year, they almost doubled, and rose relentlessly to $21.5bn in 2014—almost six times the 1990 level. Why such different outcomes?

“Impressionist art was so overpriced in 1990. There was a bubble in the market,” says Pownall, who explains how a capital gains loophole in Japan’s tax system triggered aberrational demand for art and real estate. “The 2008 downturn was due to the global recession. The art market itself had become global by then,” she adds.

Over the past 30 years, thanks to neoliberal economic policies and globalisation, the wealthiest 0.1% of the world’s population has become far wealthier. The French economist Thomas Piketty in his landmark study, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, calculated that from 1987 to 2013 the planet’s richest thousandth saw their share of global capital more than triple, with an average annual growth rate of 6% above inflation.

This vast reserve of private capital underpins the dispensation that is today’s hyper-financialised art market. Collecting art, particularly contemporary art, has not only given the 0.1% pleasure and prestige, it has also been an alternative asset that has further enriched them through capital appreciation, opportunistic trading, tax optimisation and the collateralisation of loans.

Collecting also gave the 0.1% access to a distinctive luxury lifestyle, a convivial travelling circus of auctions, fairs, biennials and exhibitions, and all the accompanying parties and dinners.

If the art market returns to “normal,” will this be the normality it returns to?

“I don’t think there will be a structural change,” says Marta Gnyp, a Berlin-based art adviser and gallery owner, who in 2015 published the book, The Shift: Art and the Rise to Power of Contemporary Collectors. “We’re heading for a deep recession. Small businesses are suffering, but the stock market has seen a steady recovery.” She is referring to how indexes such as the US’s Dow Jones and Germany’s Dax have clawed back much of the value lost in March.

“The art market is dependent on the wealthy, and most of them haven’t been affected in the same way as the rest of society,” she adds. Her assessment is shared by many who have seen art market downturns come and go.

A graph of world art and antiques auction sales shows two major downturns in 1991 and 2009 © Katherine Hardy. Data courtesy of Rachel Pownall of Maastricht university

As in 2009, then, the wealthy remain largely untouched by the crisis. Once a Covid-19 vaccine becomes available, the art market may start booming again.

But this latest pandemic-triggered economic crisis is of a scale unseen since the Great Depression and even beyond. The Bank of England, for example, predicts that 2020 will be the UK economy’s worst slump since 1706.

“Big recessions like the 1930s have also been bad for art prices,” says William Goetzmann, the co-author of the 2014 study, The Economics of Aesthetics and Three Centuries of Art Price Records. “The small and mid-sized gallery was already stressed when Covid-19 happened. They face the same problem as other retail businesses right now. My worry is that they will also fail, and with them the culture around art and collecting,” he says.

With wealthy collectors no longer travelling, most art business is now conducted online. Art dealers are typically reporting a 70% drop in sales, according to a recent survey conducted by The Art Newspaper and Pownall. Up to a third of galleries are expected to fold, with smaller ones particularly vulnerable. The shift to online auctions has seen an equally dramatic slump in secondary market revenues at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips.

“I hope we will not be losing too many of the critical smaller galleries, but inevitably some galleries may close,” says Will Lunn, the founder of Copperfield, a contemporary art gallery in south London. “Between Covid-19 and Brexit, it is a confusing time. We will weather the storm and be there for our artists on the other side,” adds Lunn, who “always planned for whatever the next hurdle would be” after the last recession.

Eager to play down fears of a 1991-style crash, players have been keen to flag up online sales of multimillion-dollar works by the market’s deified names

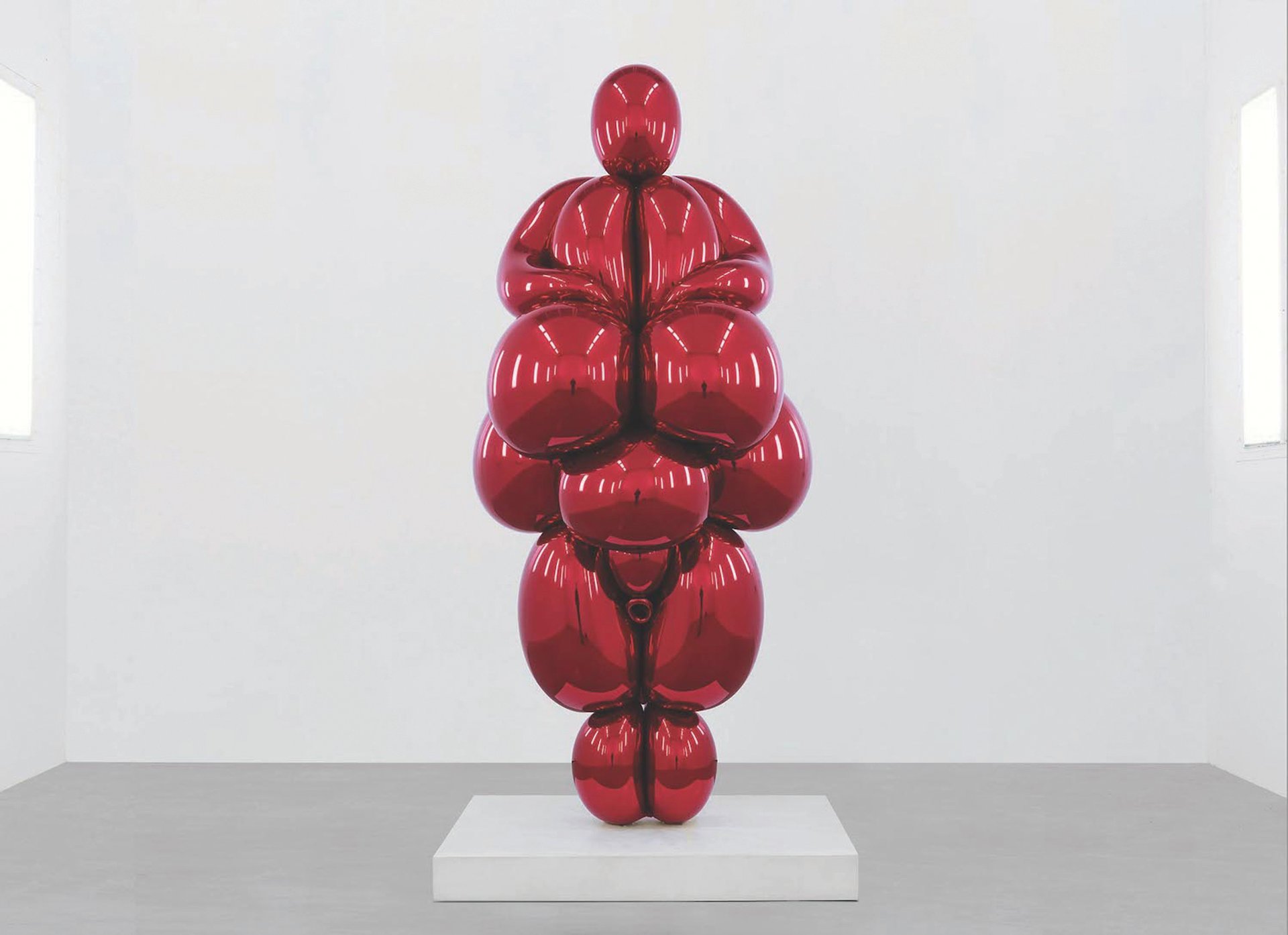

Hauser & Wirth says it sold a new work by Mark Bradford for $5m at the Art Basel fair’s virtual VIP preview day in June. Meanwhile, David Zwirner says it found a private buyer for the 2013-19 Jeff Koons sculpture, Balloon Venus Lespugue (Red), the Paleolithic goddess seemingly encased in a shiny fat suit, for $8m via the gallery’s online viewing room.

Jeff Koons’s Balloon Venus Lespugue has just sold for $8m © Jeff Koons

Sotheby’s and Christie’s have devised hybrid “clicks and mortar” auctions, live-streamed to recapture some of the theatre—and turnover—of their New York evening sales. Works by blue-chip names such as Francis Bacon, Pablo Picasso, Roy Lichtenstein, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still have attracted eight-figure price estimates.

Meanwhile, the rest of society has been grappling with a pandemic, recession, civil unrest and mass unemployment. The 99.9%, like T.S. Eliot’s king, have been on a life-changing journey.

“We live in Marie Antoinette times,” says the London-based Modern British art dealer Offer Waterman. “The wealthy always want to spend their money, but collectors will be more low-key. They will adorn their own homes.”

The multibillion-dollar top end of the art market, the end that gets the most media attention, has in recent years become a glaring symptom of income inequality. Now, as systemic racism comes under widespread scrutiny and protestors pull down statues that embody colonial oppression, a market value system based overwhelmingly on a pantheon of old or dead white male artists looks increasingly out of step with these febrile times.

“When the recovery began, it was gradually discovered that some of the casualties of the depression bore a permanent look,” wrote Gerald Reitlinger in his masterful 1961 study of the art market, The Economics of Taste, describing the after-effects of the 1929 Wall Street Crash. “In 1930 the market almost retained its old look,” he continued, but then the depression “gave the coup de grace” to items that had “already been on the way out”.

Will “investment-grade” artists such as Christopher Wool and Rudolf Stingel fall off the market pedestal in the 2020s, as George Romney and Thomas Lawrence did in the 1930s? How long before a Jean-Michel Basquiat painting sells for more than $200m?

To be fair, works by admired artists of colour, as well as by female artists, have been appealing to the ever-resetting tastes of collectors for some time now. But that’s the thing about the art market. Regardless of what’s happening in the wider world, the dispensation stays the same. It’s just the gods that change.