In January, the Brazilian photographer Claudia Andujar travelled to Paris with the Yanomami shaman and tribal leader Davi Kopenawa to inaugurate her career retrospective Claudia Andujar: the Yanomami Struggle at the Fondation Cartier pour l'art Contemporain. The exhibition comprised more than 300 archival photographs she captured in the five decades she spent photographing the indigenous Yanomami tribes, an ancient linguistic civilisation who reside in a remote but demarcated 93,000 sq. km region of the Amazon rainforest along the Venezuelan and Brazilian border.

Slated to run until May but since moved online due to the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic, the exhibition underscored Andujar’s role as an activist for the Yanomami, for whom the pitfalls of modern society—like disease, deforestation and climate change—are a constant threat. Now, as the pandemic spreads into Yanomami land, Andujar’s work “has become even more urgent”, says Thyago Nogueira, who curated the Fondation Cartier exhibition after closely collaborating with Andujar for around four years.

On 9 April, a 15-year-old Yanomami boy named Alvaney Xirixana became the first Yanomami to die from Covid-19, likely due to contact with illegal workers in the area, as around 20,000 illegal miners and loggers are estimated to operate in the region.

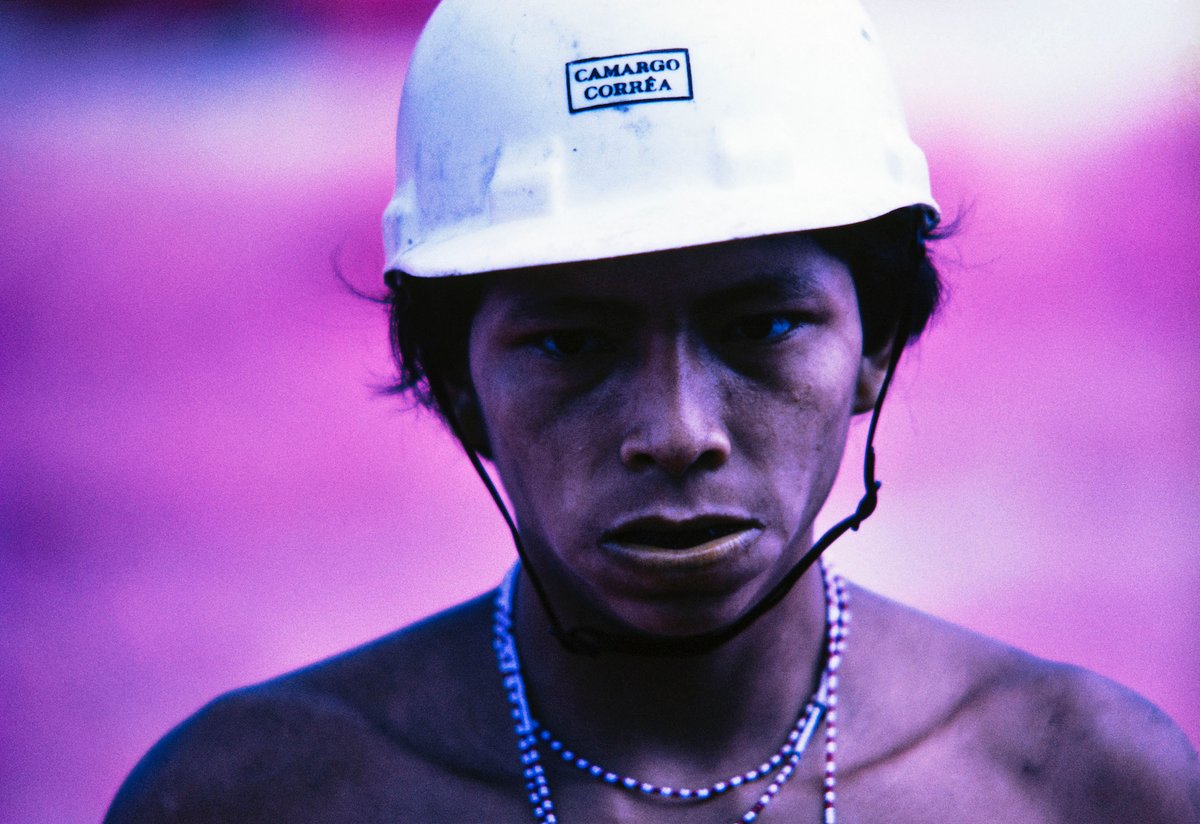

From the Marked series, double exposure, Brazil, 1983 © Claudia Andujar; Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles and Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain

The nearly one million indigenous people who reside in Brazil are perhaps among the most vulnerable to this epidemic. The Yanomami themselves have lived through several deadly viral epidemics since the 1940s, notably the measles and flu. Nogueira says the current pandemic “has the power to completely annihilate the Yanomami civilisation”, which has a population of around 38,000 people. “The Yanomami know how to fight the diseases of the forest but not diseases from the outside, and the public health system provided [in Amazonas and elsewhere] has further collapsed because of coronavirus”, Nogueira says.

As the virus continues to spread in Latin America, with more than 2,500 confirmed deaths in Brazil, Bolsonaro’s government has doubled down on coronavirus denialism. Within the last week, Bolsonaro threatened a military takeover in order to end shutdowns and restart the economy despite recommendations from the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other experts, as well as widespread outcries from citizens in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo; he has not yet addressed the death of Xirixana.

Critics of Bolsonaro have long pointed to his inhumane treatment of the Yanomami as he has proposed reversing a 1993 decree—an order that Andujar and Kopenawa helped to establish—that demarcated Yanomami territory. As recently as February, the president has introduced legislation to legalise mining and commercial farming in the area, effectively displacing them from their Indigenous lands for corporate gain.

Claudia Andujar, Journey by pirogue, Catrimani, Roraima, 1974 © Claudia Andujar; Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles and Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain

Andujar’s photography career has been dedicated to raising awareness of the Yanomami plight as industry and urban development encroach on their territory to not only prevent greedy government takeover but also the spread of disease due to contact with industrialised society.

“What she and Kopenawa sought to achieve and accomplished in the 1980s was to fight against the genocide of the Yanomami due to the invasion of diseases that happened once they were integrated with the outside world” around the 1970s, Nogueira says. “The government and the National Indian Foundation, which is meant to support the Yanomami, did not provide—and are not providing—an adequate health care system for them; many of Kopenawa’s descendants themselves died from other epidemics.”

In the case of Xirixana, who was misdiagnosed and discharged several times by local clinics before being admitted to a hospital in critical condition due to coronavirus complications, Nogueira adds: “There are ongoing complicated negotiations between the municipal government and the Yanomami; the government has to bury him with sanitary precautions, but the Yanomami want the body of the young man returned in order to perform the correct funerary rituals. The case just highlights the tribes’ main worry—illegal invasion of the land, where mining is multiplying and there’s no enforcement by the federal government.”

Andujar, who is 88 years old, has been isolated in her home in São Paulo for her own protection since the outbreak, and Kopenawa has returned to Yanomami territory and is unreachable. But the Fondation Cartier has launched a comprehensive digital stand-in for the exhibition, which explores the images Andujar captured—including photographs of some of the first miners and loggers to integrate with the Yanomami in the 1970s and of the Yanomami being vaccinated and treated for diseases newly introduced to their civilisation, which carry an ever-more resonant message during the ongoing pandemic. Other parts of the exhibition explore previously undocumented aspects of the Yanomami like their complex cosmology, shamanic rituals and beliefs on the afterlife.

Claudia Andujar, Antônio Korihana thëri, a young man under the effect of the hallucinogen yãkoana, Catrimani, Roraima, 1972–76 © Claudia Andujar; Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles and Fondation Cartier pour l'Art Contemporain

In the future, Andujar’s archive of more than 25,000 images of the Yanomami will be the most comprehensive record of how the tribes lived as their world became entangled in the ills of colonisation and capitalism, and as their lands became hotspots for rampant political corruption and lethal disease. In a previous interview with The Art Newspaper, Nogueira, who is the head of the contemporary photography department at Instituto Moreira Salles in São Paulo, confirmed that there are plans to digitise Andujar’s archive in order to preserve it for future generations.