A row over the number of penises depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry has deepened, with two medieval scholars clashing over a mystery appendage depicted in the famous eleventh-century embroidered work.

George Garnett, a professor at Oxford University, says there are 93 depictions of male genitalia in the tapestry. But Christopher Monk, an expert on Anglo-Saxon nudity, claims that he has found an extra phallus, outlining his reasons in a blog published yesterday.

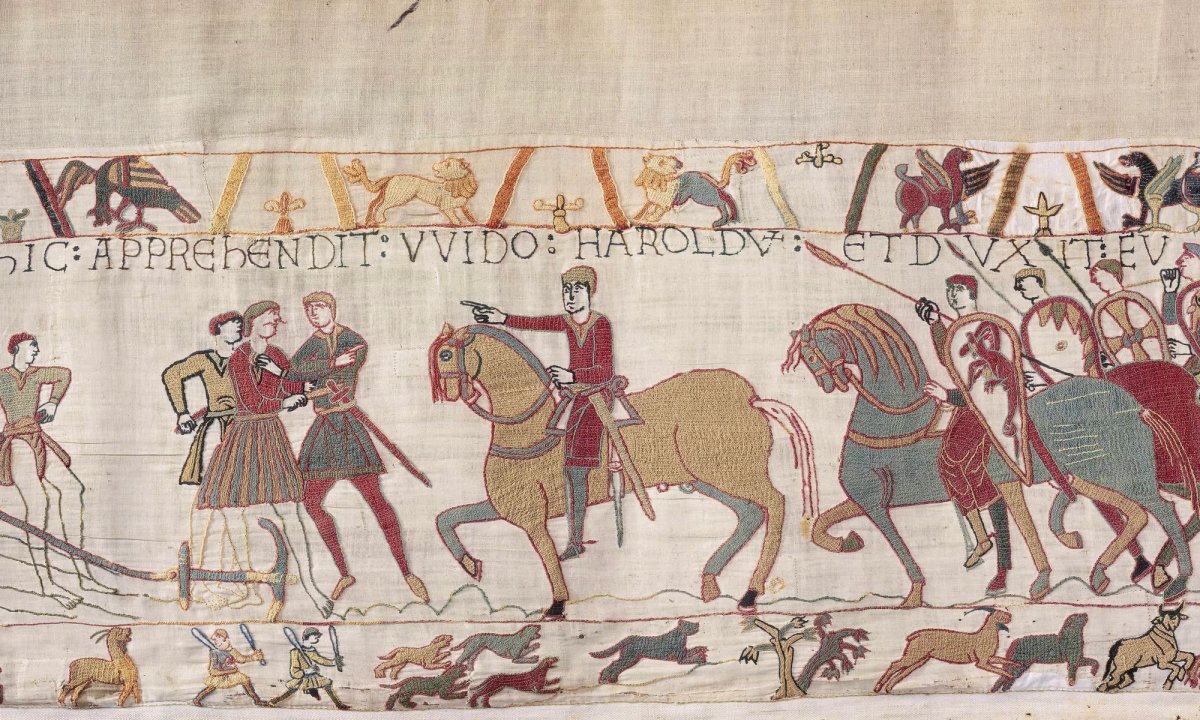

The Bayeux Tapestry embroidery, measuring 70 metres long and 50 centimetres high, was created in the 1070s, with nine panels comprising 58 scenes showing events leading up to the Norman Conquest of England after the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

Dagger or dangling appendage?

In 2016, Monk published an essay explaining that “previous commentators seemed to have missed the genitals of this running, club-wielding man”, referring to a running figure, depicted in the tapestry border, who has a dangling item beneath his tunic.

In 2018, Garnett waded into the debate, writing a piece for History Extra entitled The Bayeux Tapestry with knobs on: what do the tapestry's 93 penises tell us? Garnett counted the number of penises in the Bayeux Tapestry, giving a total of 93—five on men shown in the top and bottom borders and 88 on horses.

Garnett discussed his findings recently on the BBC History Magazine podcast, History Extra, reiterating that the border figure’s mystery appendage is the scabbard of a sword or dagger as “right at its end is a yellow blob”, which he believes is a depiction of a brass element.

“If you look at what are incontrovertibly penises in the tapestry, none of them have a yellow blob on the end,” he told History Extra, highlighting the scholarly aspect of his research. “What I’ve shown is that this is a serious, learned attempt to comment on the conquest, albeit in code.”

Monk says the dangling appendage is “completely wrong for a scabbard”

Photo: Bayeux Museum

“One should never count one’s penises too quickly”

However, in his new blog post, Monk outlines why the dangling item is not, in his opinion, a scabbard. “Two things: scabbards are not shown in the Bayeux Tapestry with ornamentation at their bottom end—no [yellow] ‘blobs’ [at the end]; and the position of the dangling appendage is completely wrong for a scabbard.”

He adds: “One of the most important things when studying detail in early medieval/Anglo-Saxon artwork is to observe patterns. In the case of male genitalia in the Bayeux Tapestry, human and equine, there are patterns for a penis … they are drawn consistently.”

Monk also highlights other depictions of genitalia in the tapestry that look similar to the disputed phallus. Another image for instance shows some testicles hanging beneath an axe-wielding figure.

“What we should observe here is the close similarity between his visible testicles and the circular bits of our running man’s appendage,” Monk says. Restoration work on the tapestry by Victorian conservators may also have distorted the penis shaft, he adds.

Monk acknowledges that firm conclusions are a rarity when it comes to interpreting the Bayeux Tapestry, but asserts: “[These are] male genitals, not a scabbard. That’s where the internal, art historical evidence points ... New ideas and theories rise up frequently. Or, put another way, one should never count one’s penises too quickly.”

Monk says he hopes his post will “put an end to the academics-at-loggerheads debate, as it’s been rather amusingly characterised by the UK press”.