Every year, visitors to the great London auction houses can see some of the finest and most eclectic examples of every major branch of artistic achievement of the last 2,000 years. For a few days at a time, Sotheby’s and Christie’s transform into choice seasonal museums, where there are serviceable surveys of the European Renaissance, a mini Pompidou’s worth of 20th-century Modernism, or collections of orientalist painting such as you will see nowhere else in London. And every so often, there are rare and unusual gems that transcend mere quality to tell a story of their own; a previously unexhibited Pieter Bruegel the Elder, perhaps, or an exquisite Persian carpet that has spent 400 years in a Japanese castle.

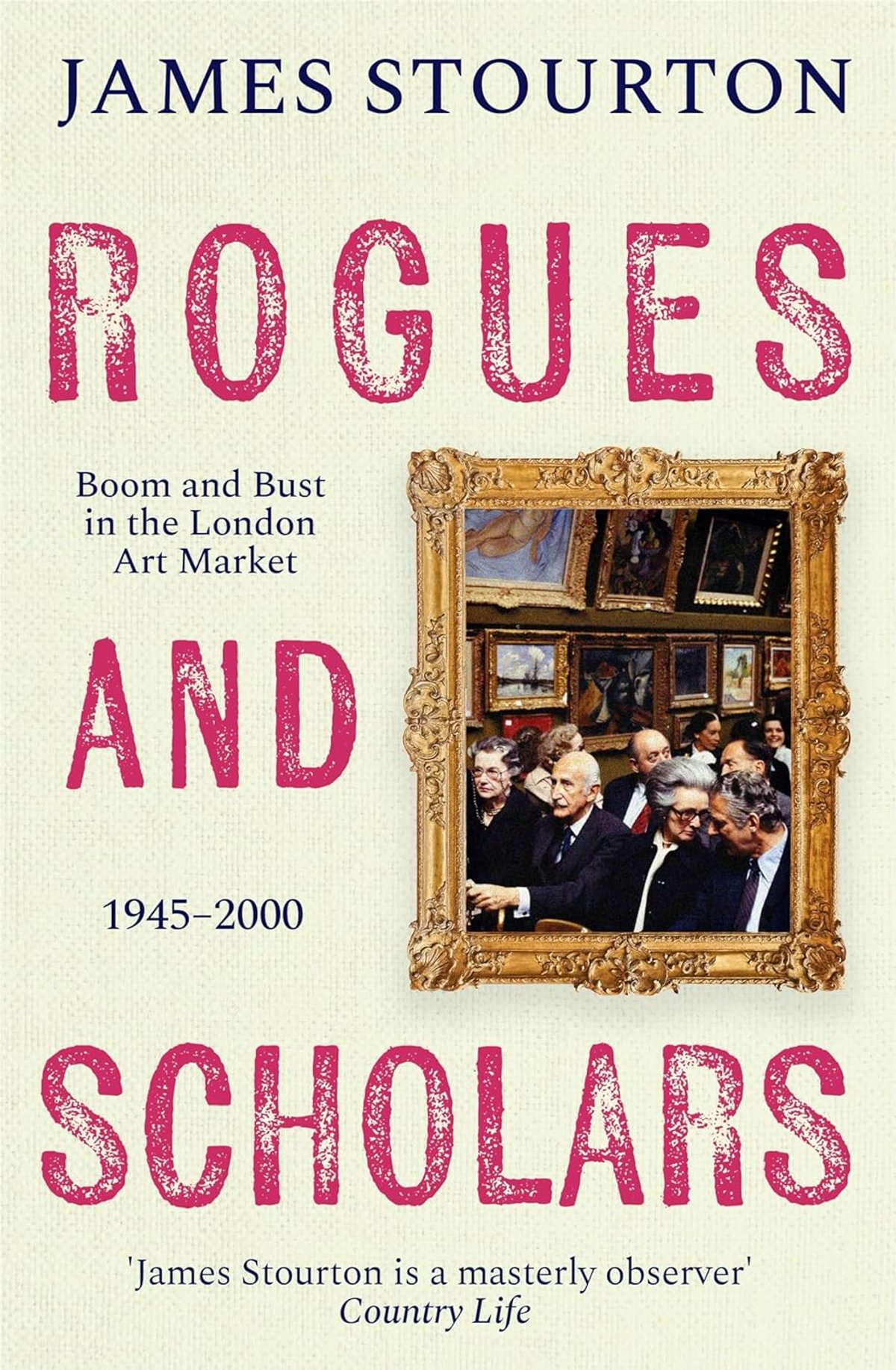

With blockbuster auctions and art fairs in New York, Switzerland and Hong Kong that draw the world’s super rich, London may no longer sell the most art, but its auction houses remain unique for their range and quality, meticulously displayed and catalogued for the benefit of buyers and window shoppers alike. Rogues and Scholars shows how that market arose in London in the years following the Second World War. James Stourton, a former chairman of Sotheby’s UK, has drawn on copious source material, including press reports, published memoirs and original interviews, to highlight the scholarly and occasionally roguish characters who turned the disposal of recondite artefacts into a multi-billion-dollar global industry. In this definitive, highly readable history he has argued for the central role of London in the genesis of the market we know today.

For Stourton, it all began with Sotheby’s sale of the Goldschmidt collection of Impressionist art in October 1958. For centuries, collectors had bought from disparate sources. By the 19th century, grand London galleries like Agnew’s or Colnaghi dominated the secondary market, while new industrialist fortunes on both sides of the Atlantic gave rise to powerful dealers such as Joseph Duveen (1869-1939). Around the same time the Impressionist revolution in Paris saw the emergence of grand European gallery dynasties, of which the behemothic Wildenstein Institute is a notable survivor. Meanwhile, Stourton says, Christie’s always worked “to serve the British aristocracy in a cosy monopoly, with Sotheby’s dealing with the contents of the library”.

The Goldschmidt sale, comprising just seven paintings at the highest level, was a public relations triumph, turning art auctions into glamorous evening affairs, redolent of movie stars and jet-setting millionaires. It broke all records, several times over. In 1970, Christie’s was the first to sell a painting for more than £1m, and the subsequent decades saw stiff competition with Sotheby’s in a race to the top for ever higher prices. In 1956, Sotheby’s sold £2.27m worth of art and Christie’s sold £1.68m; by 1973, Sotheby’s sold £72m against Christie’s £34m (in 2024, both stood at nearly $6bn). Then, the introduction of the buyer’s premium in 1975—which allowed the auction house to take a cut from the buyer as well as the vendor—proved to be, Stourton declares, “the Big Bang of the art world”, taking the auction duopoly into the realm of big business. This rapid growth, Stourton continues, owed much to Sotheby’s chairman Peter Wilson’s idea of “persuading Americans to sell French paintings in London back to Americans”, but also to a concentration of specialist expertise, the expansion of jet travel and London’s status as the natural home of international capital.

Shaping global tastes

Stourton provides an invaluable survey of the galleries and dealers who, for a time, shaped global tastes from London: for example, the Marlborough Gallery, consisting of a duke and two émigré Austrian Jews, cornered the market for Francis Bacon and Henry Moore; the louche dealer Robert “Groovy Bob” Fraser partied with The Rolling Stones and helped popularise Pop art; Christopher Gibbs made antiques fashionable with an unfailing eye for the unusual; and Robin Symes for the first time sold antiquities as timeless works of art, thanks in part to a network of quick-fingered tombaroli (grave robbers).

But what future is there for the world Stourton describes? With a few exceptions, London’s traditional dealers have lost their vitality, due partly to the inevitable expiry of a business model that consisted of selling marked-up auction purchases. The highest end of the market has moved across the Atlantic, although a healthy competition between London and New York continues to benefit both. And, with the two major auction houses taking an increasingly corporate turn, the cachet of the London art market—the quality of its specialists—seems at risk of neglect.

And recent decades have seen a steady stream of art world scandals, of which Orlando Whitfield’s All That Glitters (2024) provides the most recent account. These seem the inevitable result of the commodification of art so comprehensively chronicled here. Changing tastes and buying habits now threaten the close nexus of market price and artistic value that sits at the heart of Stourton’s story; all his characters are marked by a deep love of objects, but they set in train forces animated by money not art.

- James Stourton, Rogues and Scholars: Boom and Bust in the London Art Market 1945-2000, Apollo/Bloomsbury, 432pp, colour illustrations, £30 (hb), published 12 September 2024

- Cyrus Naji is a writer and researcher based in Dhaka, Bangladesh