As Arab Modern art grows as a subject of interest among curators and scholars, the difficulties of conducting primary research on artists are becoming clear. Some archives and artworks are inaccessible due to conflict, while other material has been neglected. Families are reluctant to share personal records. And much of the writing about 20th-century Arab art is—unsurprisingly—in Arabic, which many researchers do not speak.

These challenges are being addressed by the al Mawrid Arab Center for the Study of Art, set up at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD) in 2021. Al Mawrid (which means “the watering place”) digitises the archives of Arab artists and critics, makes them publicly available and publishes translations of key Arabic texts into English.

“There is a big task ahead of us of redressing the gap in archival scholarship and heritage management,” says Salwa Mikdadi, the Palestinian American art historian who established al Mawrid. “There is inequity among scholars in access to these sources of material. Those scholars living in the Arab world need visas to access material in the West. And in the Arab world, there isn’t one centre like the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian [in Washington, DC] or similar places in France or England that have a repository of material about artists.”

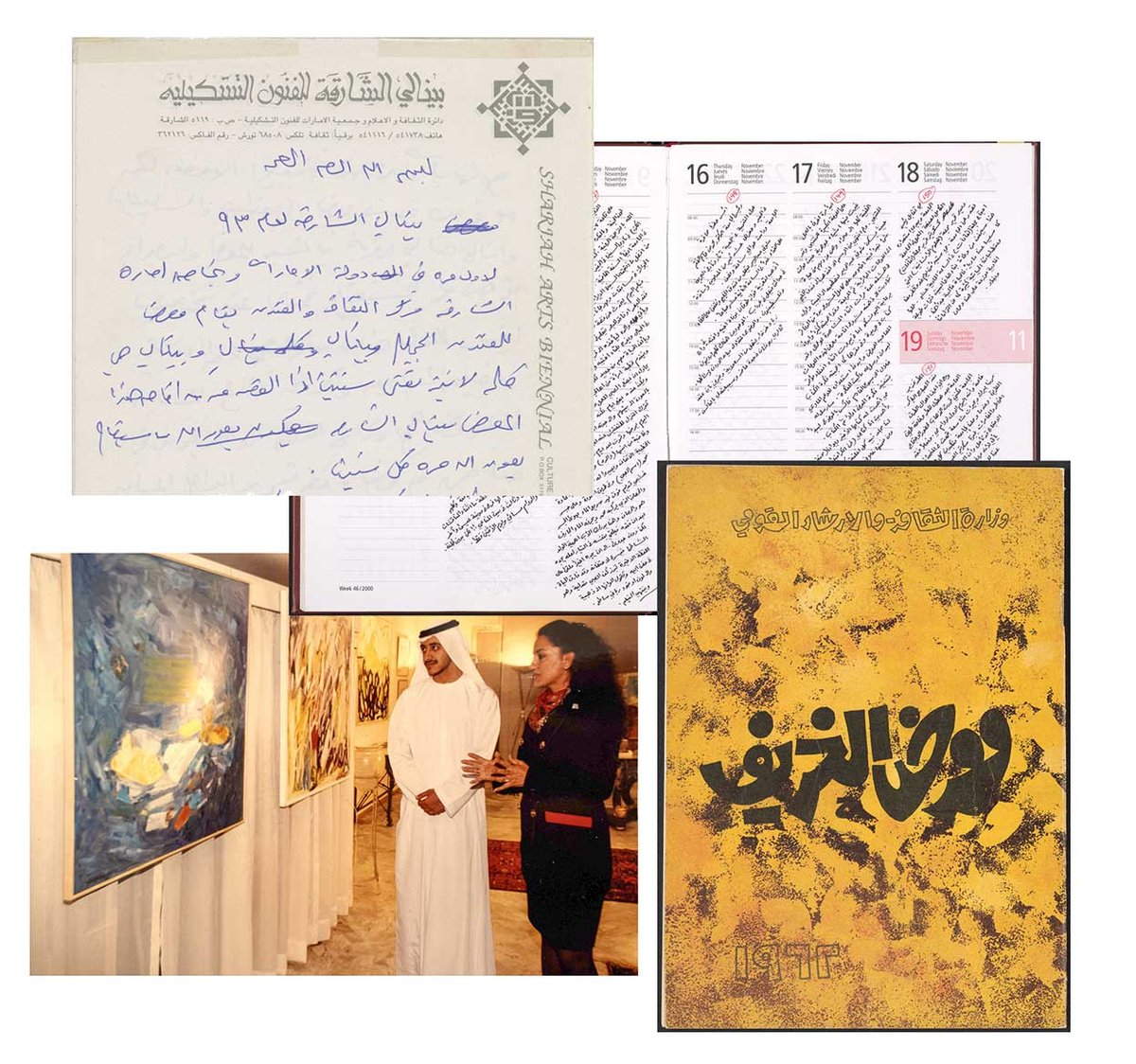

So far, al Mawrid has digitised more than 45,000 records and published numerous texts and books. Archival material has been found under artists’ beds, in cardboard boxes in attics, or infested with insects. In the worst cases, researchers clean and piece back together the letters, journals, and sketches. To make sure that the physical archives stay in their countries of origin, al Mawrid has set up digitisation centres in Arab cities such as Cairo, Kuwait, and Amman, where journals, images, photographs and writings are scanned, backed up and included in their publicly searchable database. Only in cases where the material itself is at risk, as in the case of political instability, do they bring the work to Abu Dhabi.

“Salwa has found a way to circumvent some of the reservations that individuals have about sharing their family archives,” says Sultan Sooud Al Qassemi, whose Sharjah-based Barjeel Art Foundation commissions academic research on Arab Modernism. “The family keeps the original photographs and documents, which certainly have sentimental value. She borrows them for a few days, scans them and hands them back.”

Mikdadi’s goal is not just for the material to be shared, but to help situate the scholarship within an Arab context. She notes that many of the major routes into Modern Arab art, which al Mawrid defines as 1850-1996, are motivated by overlaps with European and American movements like Surrealism. But aspects drawn from Arab culture have been left out of the picture, such as the important interchange between literature and art.

In Story of Water and Fire, which al Mawrid translated last year, the writer May Muzaffar recounts her life with the artist Rafa Nasiri, who was part of the second generation of postcolonial artists in Baghdad. It draws a picture of 1960s and 70s Iraq—and expands wider, to be a first-hand account of the US invasion of the country and the couple’s attempts to hold on to their artistic selves even amid war and exile.

Investment in education

From a larger perspective, the work of al Mawrid reflects the investment over the past 20 years of wealthy Gulf states into research and education. Education City in Doha comprises branches of Georgetown, Northwestern and six other Western universities, while Abu Dhabi set up the Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi in 2006 and NYUAD in 2010. These universities offer full four-year programmes and take both international and local students, with curricula that reflect the regional identity.

Salwa Mikdadi: “a living legend in the world of Arab art”

Shiji Ulleri Photography

But al Mawrid is also the life’s work of Mikdadi, who grew up in Jerusalem and Kuwait to Palestinian parents. She has been collecting material since the 1980s and 90s, when she travelled across the Arab world to interview artists and document their work. At the time, she says, there was no international interest in Arab art—let alone funding for her endeavours.

“I spent my own money,” she recalls. “In those days, it wasn’t unusual for many Arabs to do this kind of work pro bono, feeling that this is what we are doing for our country, to share the culture that we are so proud of.”

Mikdadi collected material from around 455 artists, including major figures such as Ismail Shammout from Palestine, Fateh Moudarres from Syria, and Rachid Koraïchi from Algeria. Mikdadi also worked to build knowledge of Arab artists in the US. In 1989 she founded the International Council for Women in the Arts (ICWA), which produced exhibitions and education programming around Arab art (both male and female). A few years later she curated a major show of more than 70 Arab women artists that began at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC and toured to three other venues. Forces of Change ended up being one of the earliest exhibitions devoted to Arab art in the US, with artists such as Etel Adnan, Saloua Raouda Choucair and Mona Hatoum.

All along, however, Mikdadi was thinking of a centre like al Mawrid. After joining NYUAD in 2016, she donated her library to its permanent collection, and now continues her work on al Mawrid’s behalf. The centre recently announced that it is looking after the archive of the artist Hussain Sharif, who was one of the pioneers of Conceptualism in the UAE. And Mikdadi and the Mawrid team are working to digitise further records, building on the trust that she has established by her work in the field.

“Salwa deserves a lot of credit,” Al Qassemi says. “She is really a living legend in the world of Arab art. A lot of us look up to her as a pioneer.”