Caravaggio was born Michelangelo Merisi in 1571 in the small town of Caravaggio, near Milan. He arrived in Rome around 1592, a young artist hungry for success, and spent the next 14 years of his life there. The city's chaos fuelled both his genius and his troubles. His criminal records tell of brawls, arrests and the murder that forced him into exile. Yet his years in Rome also sparked an artistic revolution. He pioneered a style called tenebrism, casting figures in deep shadow and piercing that shadow with stark light. His biblical scenes were raw and unvarnished, featuring wrinkled faces, dirty feet and rough gestures. Many of his masterpieces still hang in Rome today. Here are ten to see.

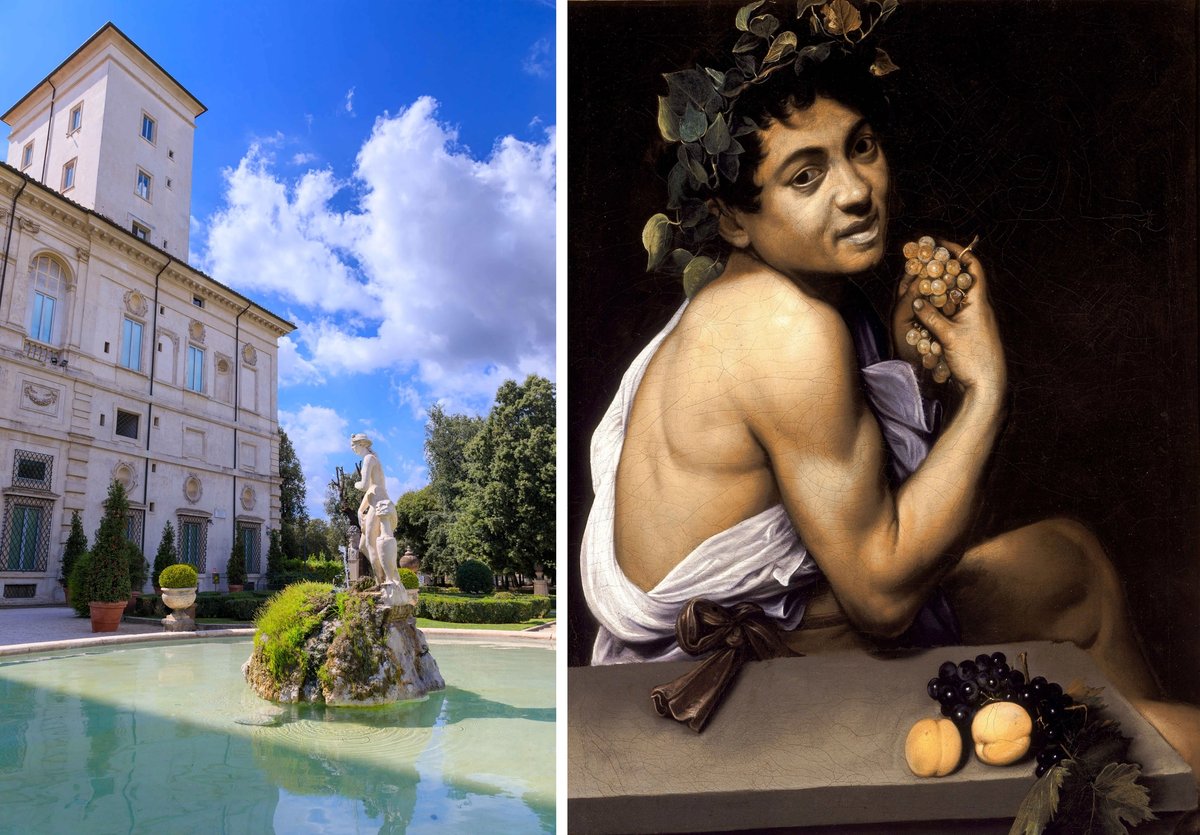

1. Sick Young Bacchus (around 1595), Galleria Borghese

Sick Young Bacchus is one of Caravaggio’s earliest works and is believed to be a self-portrait, painted with the aid of a mirror. It was created during his first years in Rome and likely reflects his weakened state following a six-month hospital stay. His languid pose is more feverish than seductive, his bluish complexion, grimace and tilted head contrasting sharply with the lush green grapes he holds. The painting marks the beginning of the innovative style for which he would become known, showcasing his mastery of Lombard naturalism and chiaroscuro. The painting is one of eight Caravaggio works in the Galleria Borghese’s collection, which also includes Boy with a Basket of Fruit (1593), David with the Head of Goliath (1609–10) and Saint Jerome Writing (around 1606).

Directions here. Book tickets here. Note: This work is temporarily on view in the Palazzo Barberini exhibition Caravaggio 2025 (until 6 July)

2. Judith Beheading Holofernes (around 1599), Palazzo Barberini

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This painting is a pinnacle of Baroque drama, capturing the gruesome moment Judith slays the Assyrian general Holofernes. The gory explosion of blood, depicted with unflinching realism, is offset by Judith’s composed yet tense demeanour—her furrowed brow suggesting internal turmoil. The old maidservant, wrinkled and weathered, watches with grim satisfaction. Holofernes’ spasming limbs and gaping mouth viscerally capture the moment of death—making this work a far cry from the noble executions often depicted in Renaissance art. Its stark lighting and psychological intensity reflect Caravaggio’s unfiltered approach to storytelling. The work was long thought to be one of two versions by the artist, but a second alleged version surfaced in 2014 in a Toulouse attic, sparking debates over its authenticity. Palazzo Barberini also holds St. Francis in Meditation (1604-6) and Narcissus (around 1597-99).

Directions here. Book tickets here. Note: This work is temporarily on view in the Palazzo Barberini exhibition

3. Jupiter, Neptune and Pluto (around 1597), Villa Aurora

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Caravaggio’s only known mural, painted in oil on plaster rather than fresco, was commissioned by Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte for his private study at the Villa Aurora, a lavish 16th-century property in the heart of Rome. The painting serves as an allegory of alchemy: Jupiter represents air and sulphur, Neptune water and mercury, and Pluto earth and salt. The celestial glow of Jupiter contrasts with the murky depths of Pluto’s underworld, while Neptune hovers between, embodying fluid transformation. The bold foreshortening makes the gods appear as if they are floating above the viewer. The mural remains a rare example of Caravaggio’s skill beyond easel paintings, though its future is uncertain following a lengthy legal dispute over the ownership of the property.

Book tickets here. Note: This work is viewable via tours organised in connection with the Palazzo Barberini exhibition. See here

4. The Entombment of Christ (c. 1600–1604), Vatican Museums

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This altarpiece is regarded as one of Caravaggio’s greatest masterpieces and represents a peak in his mature style. It was originally commissioned for the Chiesa Nuova before being moved to the Vatican Pinacoteca after its return from France in 1817. It offers a break from traditional depictions of Christ’s burial, as instead of being shown in the tomb, he is presented on the anointing stone—used to prepare his body after his death—a decision that adds to the immediacy and emotional weight of the scene. The muscular, aging Nicodemus struggles under Christ’s lifeless figure. The dramatic chiaroscuro, meanwhile, highlights the desperate, grieving figures above, particularly the Virgin Mary, frozen in sorrow. The strong diagonal composition and dynamic movement amplify the characters' humanity—reflecting an approach to realism that profoundly influenced later artists such as Peter Paul Rubens and Paul Cézanne. In this way it encapsulates Caravaggio’s profound influence on European painting.

Directions here. Book tickets here.

5. John the Baptist, Youth with Ram (1602), Musei Capitolini

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This unconventional depiction of John the Baptist brims with erotic undertones. The ram, symbolising both sacrifice and lust, injects an ambiguity that again challenges religious convention. John’s supple form, bathed in warm, golden light, exudes a seductive energy, yet his melancholic gaze suggests something deeper—perhaps a foreknowledge of his grim fate. Scholars suggest it subtly mocks Michelangelo’s idealised nudes in the Sistine Chapel. Caravaggio painted at least eight versions of John the Baptist, exploring different facets of the saint’s identity. The Musei Capitolini also houses another painting of John the Baptist attributed to Caravaggio.

Directions here. Book tickets here. Note: This work is temporarily on view in the Palazzo Barberini exhibition

6. Conversion on the Way to Damascus (c. 1601), Basilica di Santa Maria del Popolo

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This depiction of the Conversion of Saint Paul—which was commissioned by Tiberio Cerasi, the treasurer general of Pope Clement VIII—is intense and unflinching. Paul lies sprawled on the ground, almost upside down, struck blind by divine light. His rigid limbs and open hands suggest shock rather than triumph. Caravaggio dresses him as an ancient Roman soldier, breaking from his usual contemporary clothing. A towering horse dominates the frame, its weighty form indifferent to the revelation. The groom, steady and unconcerned, holds the reins. The painting’s harsh contrasts and bare realism strip the scene of grandeur, focusing instead on Paul’s physical vulnerability. An earlier rejected version remains in the Odescalchi Balbi Collection.

Directions here. Visitor information here.

7. The Calling of St. Matthew (1599–1600), San Luigi dei Francesi church

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

This work, part of Caravaggio’s Saint Matthew cycle, captures the transformative moment when Christ summons the tax collector Matthew to follow him. Most scholars identify Matthew as the bearded man pointing at himself, as if asking, “me?” in disbelief. A diagonal beam of light symbolising divine intervention pierces the darkness, illuminating the man’s stunned expression. Pope Francis has spoken of visiting San Luigi as a young man to contemplate this masterpiece. The other works from the cycle—The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and Saint Matthew and the Angel—remain beside it in the chapel, making it one of the most significant sites in which to experience Caravaggio’s revolutionary approach to storytelling.

Directions here. Visitor information here.

8. Madonna of Loreto (around 1604–6), Basilica di Sant'Agostino

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Caravaggio’s Madonna di Loreto is yet another example of how the artist broke from traditional Christian iconography of the time. Mary stands barefoot in a doorway, lit by a warm glow. She looks human, not distant or divine, with just the halo above her head giving her status away. Two weary pilgrims kneel before her, a pair of dirty feet visible. Their hands are clasped in prayer, their faces lifted in devotion. The scene feels real, not idealised, and Caravaggio’s dramatic light makes the moment vivid. Many viewers were shocked by the painting at the time, but today it is praised for its honesty. It reflects the Church’s bond with the poor, showing faith as something lived, not just worshipped.

Directions here. Visitor information here.

9. Rest of the Flight into Egypt (around 1597), Galleria Doria Pamphilj

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In Caravaggio’s first large-scale religious work, a violin-playing angel, its wings barely visible, evokes the bard Orpheus from Greek mythology as he serenades a sleeping Madonna and Child. An elderly Joseph holds up a score which, according to expert analysis, is based on the Bible’s Song of Songs, a love song to the divine. While the figures are idealised, the donkey’s wet eyes lend an earthly quality. The setting—a verdant, uninhabited glade—is more dreamscape than refuge. Rarely would Caravaggio allow such free play of detail, with ornate drapery, tangled foliage and snaking cloth visible in the composition. The painting was intended an allegory of music as sustenance providing nourishment for souls in flight.

Directions here. Book tickets here.

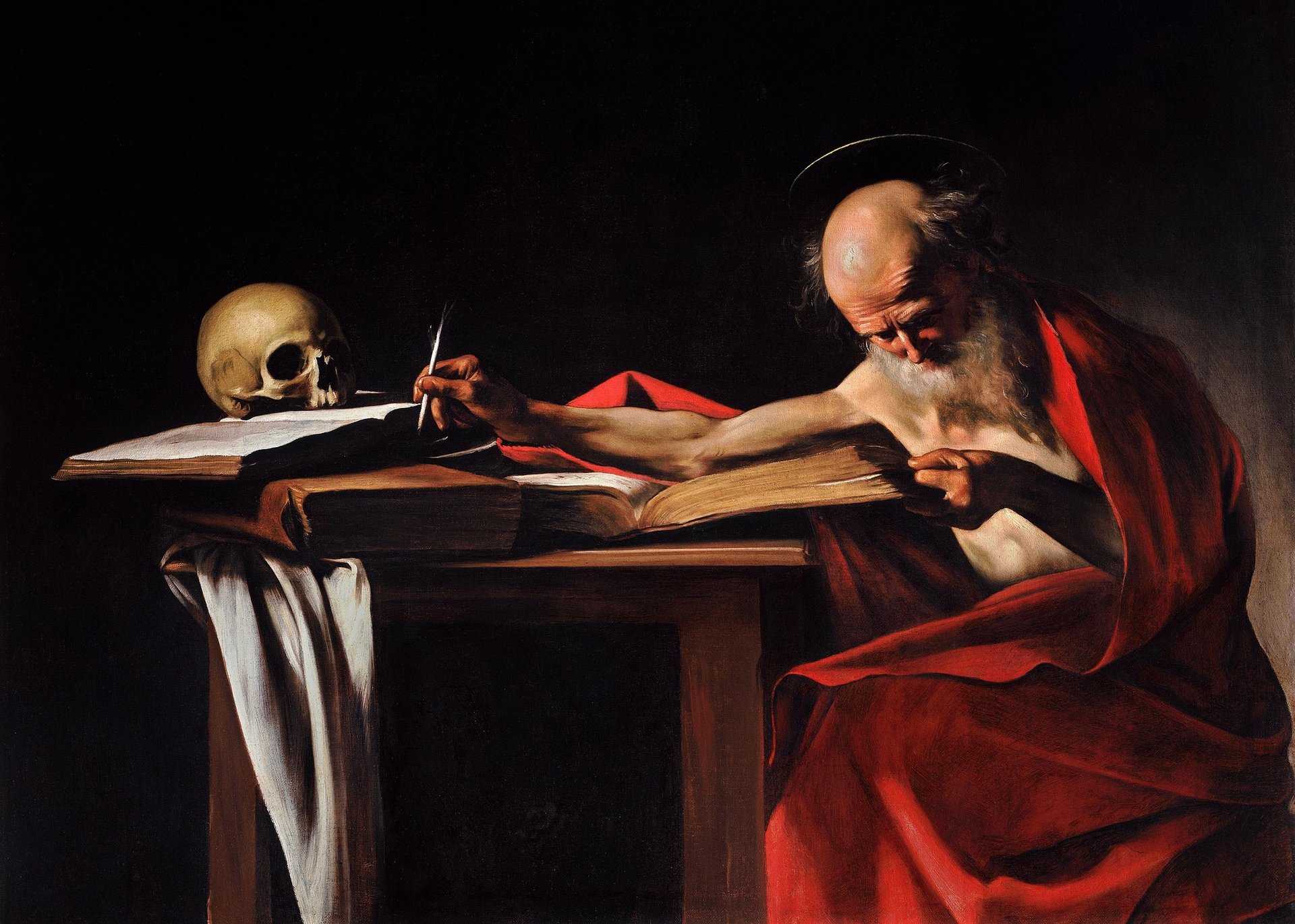

10. St. Jerome Writing (around 1606), Galleria Borghese

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In Caravaggio’s St. Jerome Writing, the aged saint bends over his translation, one sinewy arm stretching toward an ink well. His head is directly aligned with a skull, providing a chilling memento mori. Commissioned by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, the work is split between warm flesh and cold shadow, heightening the tension between life and death. Loose brushwork and abrupt details have led some to believe it was left unfinished, yet its rawness—Jerome’s gaunt expression, the austere lighting—only sharpens its power. A brutal meditation on mortality, faith and the fleeting nature of human effort.

Directions here. Book tickets here.

- Caravaggio 2025, Palazzo Barberini, Rome, until 6 July