Total star rating: ★★★★

The works: ★★★★

The show: ★★★★

In the first room of the David Hockney exhibition, which opens at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris on 9 April, there are pictures loaned from institutions from all over the world: London, Oslo, Dusseldorf, Melbourne, Milan, Dallas. And who knows where else. The rest have been prised from private collections, including Berlin: A Souvenir (1962). The work—with its blur of chaotically fractured figures—is a knock-out. With so many treats just in this opening suite, you begin by wondering how the next 10 rooms will turn out.

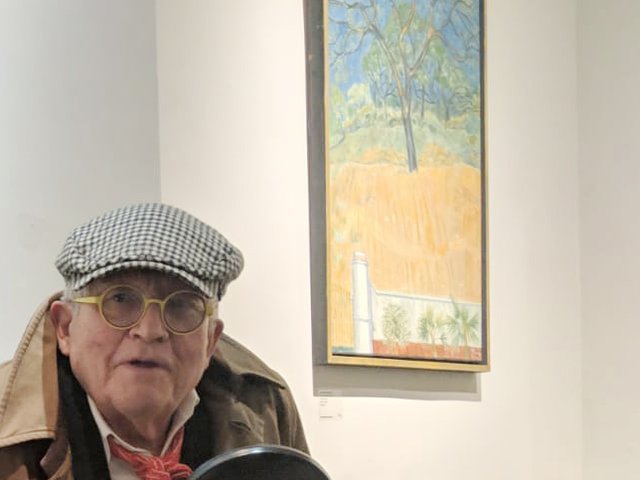

The exhibition is called David Hockney 25, and it advertises itself as focusing on the last quarter century of the British artist’s practice. But don’t be fooled by that. It goes back to the very beginning, starting with a portrait the 18-year-old Hockney made of his father, an accountant, in 1955. When Hockney came to visit the show earlier this week, says Suzanne Pagé, the artistic director of the Fondation Louis Vuitton, he spent a long time in front of it. “It was very touching. He’s a very emotional man,” she says.

This is the biggest exhibition of Hockney’s work ever staged, and fills the foundation, which incidentally was designed by his friend Frank Gehry, the California-based architect whose portrait hangs a lot further on. You cannot blame Hockney, who is 88 and constantly in the care of two nurses, to want to put it all out there with bells on. But should he?

David Hockney, Frank Gehry, 24th, 25th February 2016, from the series 82 Portraits and 1 Still Life (2013-2016)

© David Hockney. Photo: © Richard Schmidt

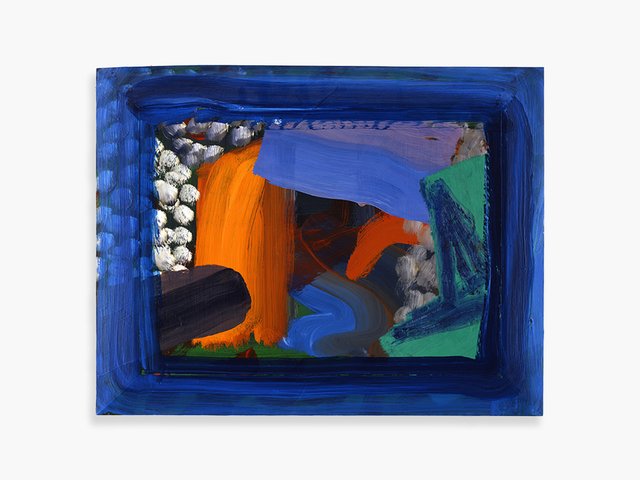

Well, actually, yes. It’s a joy to see those 1970s Los Angeles swimming pools again, and the beginnings and ends of a five-year relationship with the dazzling blond Peter Schlesinger, hovering at the water’s edge in his salmon pink jacket; to luxuriate in the 1968 portrait of Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, sitting side by side in Hockney’s first double portrait of the kind. Then all of sudden it’s 1990 and you’re on the Pacific Coast Highway and in the Nichols Canyon—searingly bright landscapes feeling like the lovechild of Van Gogh and Cezanne on a sugar rush. They are huge in scale and dramatic in mood, and tell you how Hockney saw these scenes—as hyper vivid rushes of colour and form. But they are rendered in the most meticulous detail. Hockney is a fabulous painter.

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash (1967)

© David Hockney

While Hockney, his partner John-Pierre Goncalves de Lima, and his studio assistant Jonathan Wilkinson certainly applied themselves to this exhibition, the guest curator is Norman Rosenthal, the British art historian who at 80 still knows how to put on a show. It helps that the budget was provided by the foundation, hence all that expensive shipping from places like Singapore and Hawaii. It’s hard to imagine a public institution anywhere being able to front those costs these days and round up this amount of work.

A gallery of densely salon-hung portraits shows how much Hockney likes to create a world around himself—many family members, other artists (including the late Derek Boshier and John Baldessari), the queen of arts public relations Erica Bolton, rendered in charcoal and crayon; the designer Celia Birtwell, in tartan trousers; an unnamed man in an armchair whose red velvet upholstery looks real enough to touch. The gallery next door is given over to the other great art trope—the flower painting—though Hockney’s blooms are in unremarkable vases placed on gingham cloths. It’s a nod to Matisse and the joy of the details of domestic life.

And then there’s Yorkshire, the English country where Hockney grew up. He started spending more time there in the late 1990s—leading up to and following his mother’s death—and after years in Los Angeles, its ever-changing scenery captivates him. He delves into English art history—the work of Constable and Turner—and into traditional techniques like watercolours and oils and painting en plein air, to commit it all to paper and canvas. A 12-piece suite called The Arrival of Spring (2013) shows the changing light and the gradually flowering trees and bushes between February and May, crafting space and shadow using only charcoal, as expressively as Constable used pencil.

David Hockney, Tree Tunnel, August (2005)

© David Hockney. Photo: © Richard Schmidt

Hockney’s eye is inexhaustible. He can’t stop looking and he can’t stop showing us what he’s seen. He’s like a member of the Barbizon school, who never goes indoors. He devours hedgerows and hawthorn blossom, using his iPad and iPhone to soak it all up though still painting in acrylic and oil. But there are times where it can feel there is too much to see. A section called “Four Years in Normandy” really does feel like that—220 iPad images of the few acres he roamed in the 2020 lockdown—and that’s followed by a synthetic Starry Night series of evening skies.

Still, patience is rewarded with a final room that celebrates his stage design. Hockney created opera scenography from 1975 to the early 1990s—forming an exuberant world of animal masks and butterflies, willow pattern stories brought to life and rakish pulchinelli. “I love music and when I go to the opera, I like to have something to look at,” says Hockney as the experience begins. “But theatre means collaboration which means compromise.” You get the feeling that that isn’t really his thing.

What the other critics said

Jonathan Jones in the Guardian writes: “In his latest self-portrait, Hockney sits in his London garden and beside him sprout yellow daffodils. Hockney is as reliable as those daffodils, returning at 87 as he did at 82 to show us how beautiful the world is in spite of those who try so hard to ruin it.” He adds: “You can learn a lot in this exhibition—not just about photography and the human eye but art history and perspective.” Alastair Sooke in the Telegraph writes: “The show may transform how we think about a figure occasionally rebuked for his escapism. On this evidence, Hockney is a complex, even (at times) melancholic artist, seemingly compelled—to my surprise—by a burning otherworldly yearning.” He adds: “By the end, this genial Yorkshireman’s achievement feels, yes, bigger than before, and almost overwhelming.”

• David Hockney 25, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, until 31 August

• Curators: Suzanne Pagé, Norman Rosenthal, François Michaud and Magdalena Gemra. With the collaboration of Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima and Jonathan Wilkinson, and David Hockney studio

• Tickets: €16 (concessions available)