The opulent interior of Two Temple Place, built as the London headquarters for the property tycoon William Waldorf Astor, might seem an incongruous setting for an exhibition devoted to working-class artists and life. But the tension between surroundings and subject matter makes this ambitious show of more than 150 works by 60 artists all the more compelling—especially on learning that the Temple Place mansion owes its Neo-Gothic décor to a group of largely unacknowledged working-class artist-artisans.

A major subtext to Lives Less Ordinary: Working Class Britain Re-Seen (until 20 April) is the historic under-and misrepresentation of working-class people within the UK’s cultural institutions, whether in terms of staff, visitor demographics or on the gallery walls. This is an issue that, as a white middle-class Cambridge and Courtauld Institute graduate, I acknowledge that I am part of. And while the UK’s cultural sector is at last making some progress in addressing issues of race, gender and sexuality, it is more squeamish in grappling with the hot potato of class. As the publicity for Lives Less Ordinary states: “art has a class problem”.

The exhibition’s opulent setting creates an interesting tension

Photo: Richard Eaton

“I’ve witnessed first hand the dismissal by art institutions of socio-economic disparity,” says the show’s curator Samantha Manton, who admits to having to conceal her own working-class origins in order to get on in the art world. “I’ve spent a lot of my life assimilating.” One of the key aims of Lives Less Ordinary was to counter the clichéd ways in which working-class life has historically been depicted. “It seemed that there were only a few ways in which we were allowed to be seen: in the workplace, in terms of protest or in some kind of a dilapidated environment,” Manton says. “I always felt frustrated that these reductive representations of working-class life never reflected my own experience.”

Lives Less Ordinary sets out to challenge such patronising stereotypes with work that instead celebrates the richness, complexity and often the joy of working-class life in Britain. The show’s earliest piece is Bert Hardy’s famous 1948 photograph of a jaunty pair of young boys in the Gorbals area of Glasgow, commissioned by Picture Post but deemed too cheerful for inclusion in a feature on life in the city’s tenements. Other historical works include a tender painting of a toddler in a neat domestic interior by the erroneously titled “Kitchen Sink” artist Jack Smith that has more to do with formal concerns and observing everyday life than making any social or political comment.

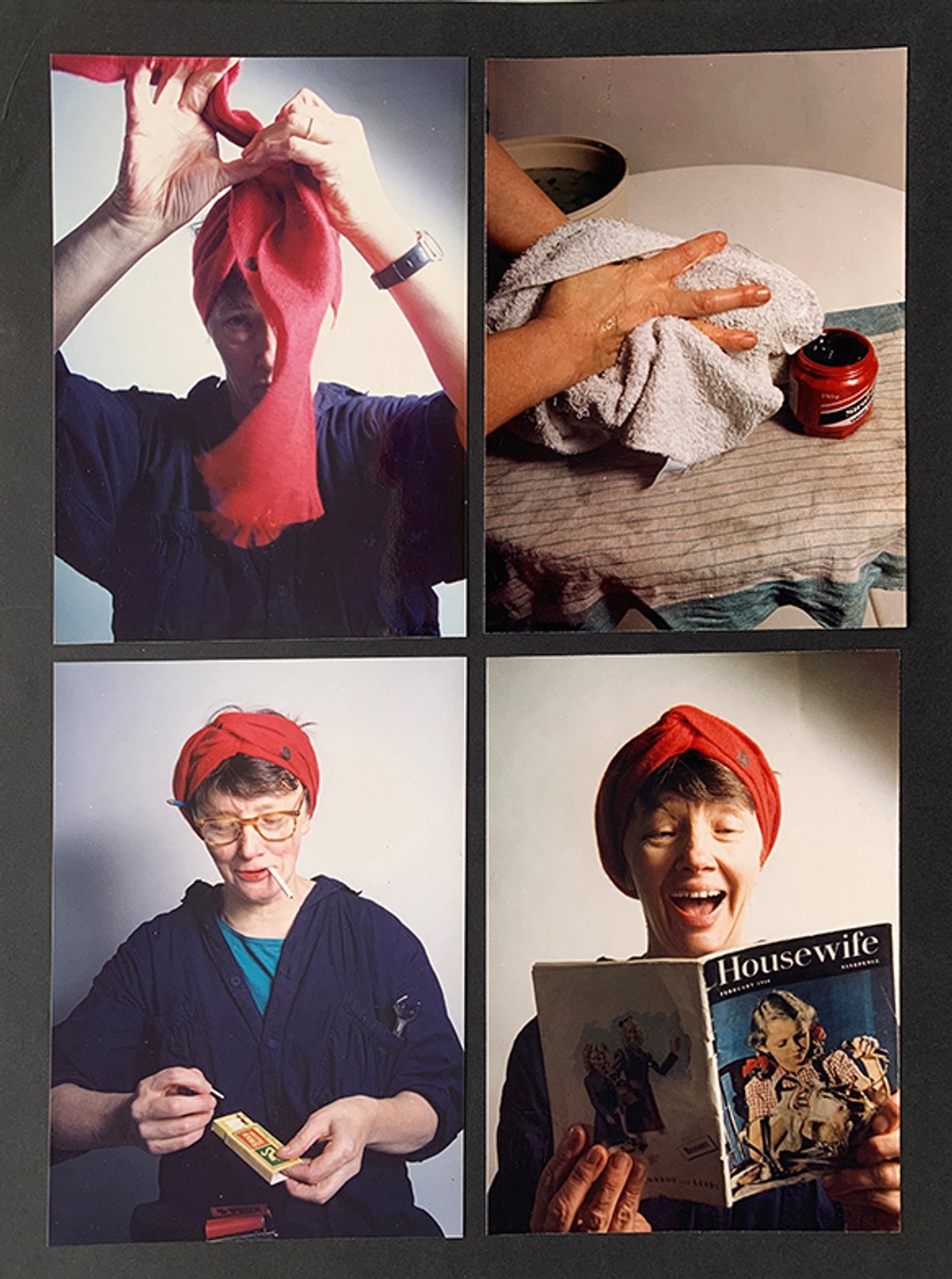

We see how, as feminism gained momentum from the 1960s onwards, Britain’s working-class women artists protested against domestic drudgery. This is present in the provocative campaigns of the Feministo network of the 1970s; Jo Spence’s bitingly satirical use of “photo therapy” to play with female archetypes in the 1980s; and Kelly O’Brien’s ongoing No Rest for the Wicked prints and engraved mops, which explore the working lives of women in her family and the ongoing legacy of being “absolutely knackered”.

Bert Hardy, The Children of the Gorbals (Gorbal Boys) (1948) © The Estate of Bert Hardy, The Hyman Collection. Courtesy of the Centre for British Photography

Other highlights include George Shaw’s atmospheric paintings of the bleak outskirts of Coventry, Beryl Cook’s gregarious gangs of women at the hairdresser’s and Connor Coulston’s giant ceramic and neon sculpture, Bailiffs be Knockin—inspired by his grandmother’s ornaments, childhood memories and queer desires. Neil Kenlock’s 1970s colour photographs of the British Caribbean community in their well-appointed homes, meanwhile, as well as works by Rene Matić and Corbin Shaw, are just some of the many works demonstrating the profusion of today’s working-class identities.

Myriad intersections

A crucial role of this exhibition is to demonstrate the myriad ways in which working class now intersects with gender, race, religion, sexuality and migrant status. Hardeep Pandhal’s hand-painted sign for the Red Lion Desi pub in West Bromwich merges South Asian and traditional British pub iconography, while the 2024 Turner Prize winner Jasleen Kaur’s tracksuit embroidered with Sikhism’s Khanda symbol speaks to her upbringing as part of a Sikh community in working-class Glasgow. There is also Matthew Arthur Williams’ two channel film Soon Come 2023 tracing the lives of relatives settling in the UK from the early 1950s, and Roman Manfredi’s intergenerational photographs of lesbian butches and studs taken in places where they grew up.

Jasleen Kaur, He Walked Like He Owned Himself (2018) © The Artist. Image credit: Touchstone Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service

With the decline of British industry, the term “working class” has become increasingly difficult to define. Lives Less Ordinary considers it as covering “anyone relying on low-paid work in the service or manual industries or low-paying clerical work, or whose families relied on low-paid work such as this while they were growing up”. But as this show confirms, the richness of Britain’s working-class experience defies easy categorisation.

“Class is not about economic circumstances alone; it’s how you’ve been shaped, your mindset and your approach to everything,” Manton says. She’s keen to stress that Lives Less Ordinary is “not a show about working-class art but about working-class Britain seen through the lens of artists who are brilliant in their own right, regardless of their origins.” Let’s hear more of these brilliant voices throughout our sector.

• Lives Less Ordinary: Working-Class Britain Re-seen, Two Temple Place, London, until 20 April