Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, the professor of art at Wellesley College, Massachusetts, has succeeded in bringing the Florence-based American artist Francesca Alexander out of the shadow cast by her friendship with John Ruskin, the leading art historian of the Victorian era, who met Alexander on a trip to Tuscany in 1882 and became a friend and admirer over the succeeding decade. Although Alexander is now little known, she received attention during her lifetime, becoming something of a celebrity in Italy, Britain and her birthplace, the US. The rare published references to her—without much hint of her broader repertoire—rely on the work for which she is best remembered: handwritten, delicately illustrated and poetic English translations of Tuscan folk ballads and songs (rispetti) that Ruskin did much to champion.

Born Esther Frances Alexander in 1837, she spent her early life in Boston, where her father, Francis Alexander, was a successful portrait painter. In 1831 he had fulfilled a long-cherished wish to visit Italy and while in Florence was commissioned to paint a portrait of Lucia, the daughter of Samuel Swett, a well-to-do merchant. Artist and sitter fell in love. Francis’s good prospects made him eligible for a marriage that brought him money and social status. He returned to Boston and resumed his portrait practice: the couple were engaged in 1834 and married in 1836. Their only child, known as “Fanny” in her youth, was born a year later.

Precocious aptitude

Told over five main chapters, this is not a story of an artist’s struggle against patriarchal limitations on young women, who were expected to attend to their social obligations and their role in home and family. We learn in chapter one that Alexander’s precocious artistic aptitude was fostered by instruction from her father. She had no other formal training and later resisted professional teaching. Meanwhile, Francis continued to hanker for Italy and made plans to return; in 1853, when Fanny was 16, the family left Boston, thereafter returning to the city only briefly as visitors.

Chapter two, “Truly an artist’s home”, sees them installed in Florence. The large Anglo-American community there enjoyed a lively cultural, artistic and political life, with a tendency to support the Risorgimento and the unification of Italy. English-speaking residents were catered for with churches, teashops, libraries and newspapers, allowing them to be almost entirely self-sufficient. Many English social habits, hierarchies and rituals were observed, but the Alexanders had studied the Italian language before their move and soon became bilingual. They attracted a bewilderingly extensive social circle, unconstrained by any perception of class or nationality. The preponderance of Italians is significant, with hardly a mention of the resident English artists that they might have been expected to know. The Alexanders fancied themselves as collectors of Italian Old Master paintings and, in a time of political turmoil, opportunities for discoveries were unprecedented, throwing many bargains in their way. With her expertise in Italian Renaissance and Baroque art, Musacchio has been able to recreate part of the picture collection, revealing some great finds, albeit representing obscure Italian minor masters, and some instances where hope triumphed over reality, with works ambitiously assigned to the early-Renaissance giants Giotto, Domenico Ghirlandaio and Pietro Perugino.

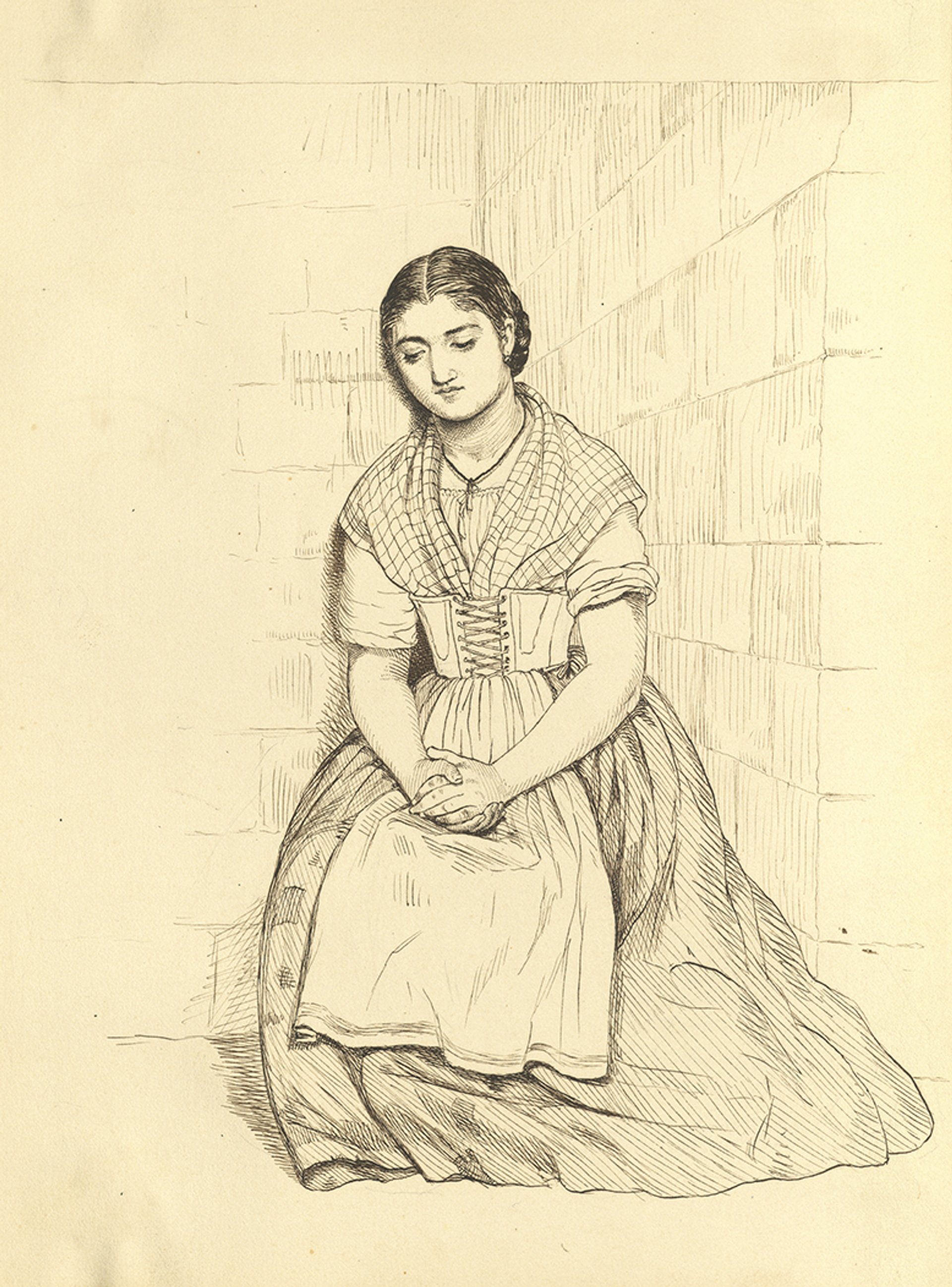

Alexander’s Cinderella (1850s) Courtesy of Wellesley College Special Collections

Chapter three, on “Fanny and Her Poor”, addresses an important aspect of her character and life, and incidentally of the relationship between mother and daughter. Francis died in 1880. Alexander’s devotion to her art proved no distraction from a close relationship with her mother, one that lasted until Lucia’s death, aged 102, in 1916. (Alexander survived her mother by only eight months.) Intensely pious, Alexander used earnings from her art to fund her many charitable endeavours, and her saintly character was linked in the minds of her friends to a romantic view of Italy itself.

Chapter four, “Francesca”, traces the Italianisation of her name, adopted quite early on; Ruskin used her Italian name and thereafter it replaced Fanny. Alexander’s art and writing concentrated on Italians and Italian life. Her loving portraits of her friends among the contadini (country people), going about their daily tasks, mark her affinity with prevailing taste for pictures of Italian peasant and working life. The highly wrought nature studies that illustrate the songs and stories were much admired in her circle and noticed in the press. On that 1882 visit Ruskin became her patron, buying one of the manuscripts, still uncompleted, of Tuscan songs and carrying off another, The Story of Ida, in 1883. The Tuscan songbook was destined for Ruskin’s St George’s Museum in Sheffield, south Yorkshire, founded in 1875 to promote art for the local labourers.

Ruskin’s admiration inspired a significant change in his views on women as artists

Ruskin continued to correspond with both Francesca Alexander (addressing her as sorella for sister) and her mother (mammina, little mother) and to visit them, the last time in 1888. He edited and published Alexander’s The Story of Ida (1883), Christ’s Folk in the Appenines (1887) and Roadside Songs of Tuscany (1888). Ruskin’s admiration for Alexander’s drawings inspired a significant change in his views on women as artists. The occasion was a lecture given in Oxford in 1883: “For a long time I used to say, in all my elementary books, that, except in a graceful and minor way, women could not paint or draw. I am beginning lately, to bow myself to the much more delightful conviction that no one else can.” The references to Alexander’s art, which were widely read on the publication of Ruskin’s Oxford lectures in The Art of England (1884), are easily recognisable, although she is anonymous.

Simple mode of life

Chapter five, “A Mediaeval Saint”, follows the fortunes of Ruskin’s publications, which seem to have profited him more than Alexander herself—although she was secure financially, as the family had always lived on Lucia’s Swett family fortune. Alexander continued to support cholera victims and other distressed Florentines. The view of her as a saint reflects the simple mode of life that she and her mother shared with their contadini. By 1890 Ruskin was no longer able to visit or correspond, while Alexander herself was not in good health and her eyesight was failing.

The brief epilogue summarises Alexander’s legacy. Musacchio represents her subject as a successful artist, but this is not an attempt to elevate her womanly contribution and there are no unsustainable claims for her talent. Her original manuscripts, with their delicately stippled illustrations and beautiful script, have endured for a reason and not only because they prompted the well-documented relationship with Ruskin. Alexander valued the manuscripts highly, charging large sums for them. Ruskin approved of her because she fulfilled her domestic and familial role and did not challenge male superiority. Her Italian life and her relationships, traced through Lucia’s lovingly compiled scrapbooks, with letters, diaries, guidebooks, newspapers and magazines, provide a vivid picture of Alexander’s place in her own times, along with a valuable and detailed account of Anglo-American life in Florence at a particularly significant period in modern Italian history.

• Jacqueline Marie Musacchio, The Art and Life of Francesca Alexander, 1837-1917, Lund Humphries, 208pp, 118 colour & b/w illustrations, £35 (hb), published 27 February

• Charlotte Gere is a 19th-century decorative arts specialist and the author of publications on jewellery, design, historic interiors and women as artists and as collectors