The British artist Richard Wright makes intricate abstract wall paintings, which can cover entire walls, ceilings and stairwells or be found in less conspicuous corners and even on the floor. Sometimes minimal, sometimes elaborate, these works are always unique and made in direct response to their setting. His sources are many and various, ranging across art history, graphic design and typography, but are always developed intuitively according to the site.

Many of Wright’s works have an intentionally brief lifetime and are made to be viewed for a finite period before being painted over. Others are more permanent, such as his intricate geometric system in gold leaf above the escalators at Tottenham Court Road station, the 47,000 stars on the ceiling of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, or his leaded glass window at Tate Britain.

Wright won the Turner Prize in 2009 and has had solo shows at Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego and Tate Liverpool, among many others. His exhibition at Camden Art Centre this month is his largest institutional show in the UK for more than 20 years.

The Art Newspaper: You are making a new wall painting for Camden Art Centre. How are you approaching the space?

Richard Wright: I want the building to be in the work, and the work to be in the building, as well as being part of everything else. The light of the space is always the beginning point, and then I look for triggers within the architecture which activate a sense of place. That always leads somewhere else, because there isn’t just a building; there’s also me and my own history. So although I might look for an idea and narratives in a building, these are ways of somehow releasing something in me. With Camden, I’ve alighted on something that I didn’t think I was going to do, that a few months ago was in the corner of my thinking but that has now crept its way into the centre.

Do you plan what you are going to do in advance or does the work unfold intuitively once you are on site?

It’s a bit of both. For a larger scale project like Camden, I’ll do a lot of drawing. At a certain point there might be eight or nine different ways that it could go, with drawings pinned all over the walls of the studio. I will go [to make the painting] with a lot of material prepared, and on the first day I’ll have some plumb lines, some bits of string that I’ll move about to position certain lines, which the work will extend from. Those lines subjectively emerge from some sense of the space and how the work will become the space, and how the space will become the work. I’ve evolved a system where I initially mark out my structure on the wall based on my drawings, and then I will hang elements from that, and see how they interact with each other. The point where the work really takes place is in the way in which these elements meet each other and how they meet the building. And that doesn’t really happen fully until I’m actually making the thing one to one.

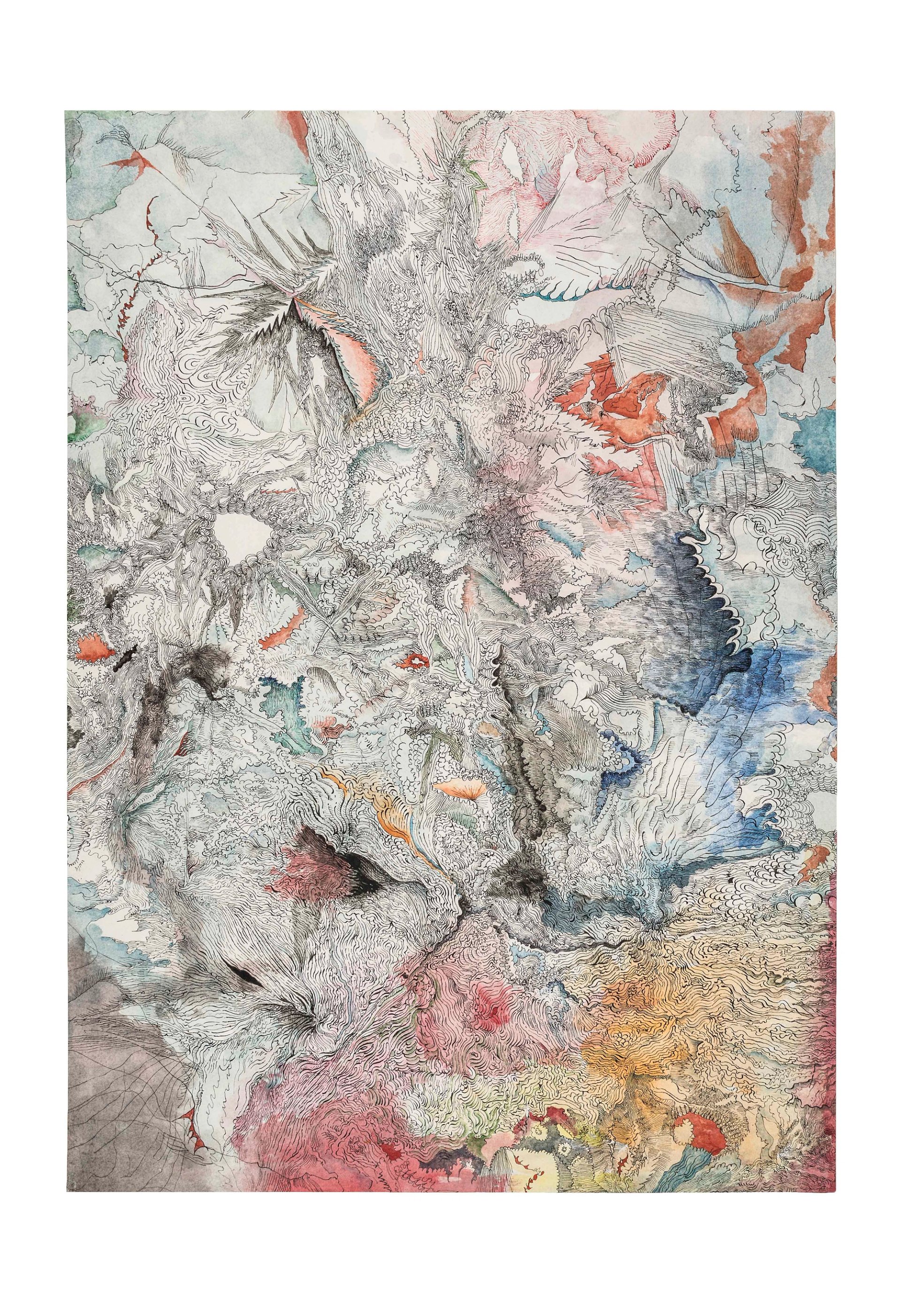

Off the wall: with works such as No Title (2017), Wright uses ink and watercolour on paper Photo: Keith Hunter; courtesy of the artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd, Glasgow

You have talked about how you regard painting as a form of reality in its own right, which goes beyond notions of representation or subject to instead offer a meditation on the act of seeing.

It’s seeking the immaterial in the material. [Georges] Seurat said that painting is the art of hollowing out the canvas and [Leon Battista] Alberti also speaks of the picture plane as the veil, and the act of painting being to somehow reach in behind the veil, beyond what is on the surface. But what fascinates me is not just wanting to look through the veil but to understand the mechanisms of how and why I am enchanted.

How do you choose your motifs?

Much of the art that interests me comes from different cultures where the personality of the individual artist is less important. Often, details have become emptied out to become tropes of style, surface activity or decorative elements in architecture, in classical and gothic buildings. But life can be breathed into them again; they can be reactivated. What strikes me is how things can come back again in a different place and a completely different culture, and you’re drawn to them again. I definitely have certain fixations and certain ways of thinking: silence and light, folding and unfolding, and of course repetition. These are all processes or actions that are fundamental to my practice and where the work might begin.

Your works often have an intentionally short life, existing for a limited period of time before being painted over, and this will be the case with Camden Art Centre. But sometimes—such as with your paintings in the Queen’s House in Greenwich or at Tottenham Court Road station—they are more permanent. Do these timeframes play into the conception of the work?

It depends on the context. With the Queen’s House I was aware that the work was part of the past as well as part of the future. It’s not just a building, it’s one of the first classical buildings in Britain, so there’s a lot going on there. At Tottenham Court Road, because the work is on the ceiling above the escalator, there’s no possibility of seeing it in a static way; you pass through it. I love this incidental aspect, the fact that it might be something people experience many times without quite knowing that it is there. It exists in some peripheral way to their journey.

Wright’s silver-leaf painting for his 2013 show in the Theseus Temple at Kunsthistorisches Museum Photo: KHM Museumsverband; courtesy KHM Museumsverband

Your use of gold leaf for Tottenham Court Road station seems to play into this fluidity.

Absolutely. Gold has this incredible liquid quality of being absent and present and positive and negative, all at the same time. It seems to be made from droplets of light and is almost not there at all. And this gives the work an almost cinematic effect; as you move up or down the escalator it starts to appear and then it gradually disappears. It might be something you thought you saw, but weren’t sure.

I destroyed all my paintings. It wasn’t a conceptual thing; it was because I thought they were shit

You studied art in Edinburgh and made figurative paintings for several years. Then, in 1988, you stopped painting and trained to be a sign writer. Why did you make this major shift and how did it feed into your current practice?

It was definitely a pivotal moment of crisis and re-evaluation. I had a sense of tremendous disappointment in what I was doing, a sense of inadequacy and failure—that the work wasn’t good, that it was one bad painting on top of another. So I destroyed all the paintings I had made. This wasn’t a conceptual thing; it was because I thought they were shit. Training to be a signwriter wasn’t about changing my direction as an artist; it just struck me as a way that I could maybe make some money. I was good with a paint brush, I love lettering and I’d done a lot of design work for posters over the years. But something happened in the process of learning [signwriting] and it was to do with the delivery of the material. Painters express themselves, whereas a signwriter wants the delivery to be invisible. The artist’s personal touch is such a big facet of modern painting, and signwriting freed me from that because it is just the paint on the thing; it doesn’t pretend to be something else. Any symbolic aspect had been emptied out. It drew me to the language of graphics, and I could go to the studio with just the idea. When I open a can of paint, I just love how it looks; I almost want to drink it.

Then there is your work in leaded glass, including two large panels that will act as skylights for the central space at the Camden Art Centre. What is it about this medium that appeals?

It’s the material-immaterial aspect—the same as what interests me about painting. It’s the fact that these things come to life and they have their own light, a reflection that projects the light back. There is the most fantastic effect of this very particular handmade glass that brings this ever-changing painting in light onto the floor or the wall.

The show will also present more than 50 drawings spanning over 25 years. Why have you chosen to include these?

More and more, I’ve become aware that drawing is a key practice and something that I do all the time in different ways. It’s a way of fixing my attention, of solidifying something in my mind and of outlining some imaginary thing or some half-forgotten thought. It’s like leaving a note for yourself for the future that you must remember. Then, when you’re looking for something, they creep back into your life. You look in a notebook or a drawer, and you think, OK, maybe that’s a starting point. The [wallpainting] work for Camden has come out of that process; it’s something I’d been thinking about doing for a long time and I just needed to find the right place where it belonged.

Biography

Born: 1960 London

Lives and works: Glasgow and Norwich

Education: 1982 BA Edinburgh College of Art; 1995 MFA Glasgow School of Art

Key Shows: 2001 Tate Liverpool; 2004 Dundee Contemporary Arts; 2009 Turner Prize; 2013 Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Represented by: Gagosian and The Modern Institute

• Richard Wright, Camden Art Centre, London, 16 April-22 June