If you thought Henri Matisse an art-world staple—a true incontournable—his work entering the public domain in 2025 is only set to cement that ubiquity. He is already “everywhere”, as Charlotte Barat-Mabille, the curator at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, puts it. “Especially since the paper cutouts, our visual culture has been steeped in his aesthetic, to the point where, today, we don’t even realise that Matisse is at the origin of that,” Barat-Mabille says. Now that you can use his works, free of copyright, to, as the British Library put it in January, “make Matisse your own”, he will soon be on every notebook, T-shirt, water bottle, silk scarf, key ring and ball-point pen out there. It suggests we will come to experience a certain fatigue, a feeling that we know the work of Matisse only too well.

However, an exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, opening on 4 April, will, without question, upend that assumption. Titled Matisse and Marguerite: Through Her Father’s Eyes, it will focus on the relationship between the painter and his daughter, Marguerite Duthuit-Matisse, who he had with his model Caroline Joblaud in 1894. He acknowledged the child when she was three and she thereafter lived with the artist and his wife, Amélie.

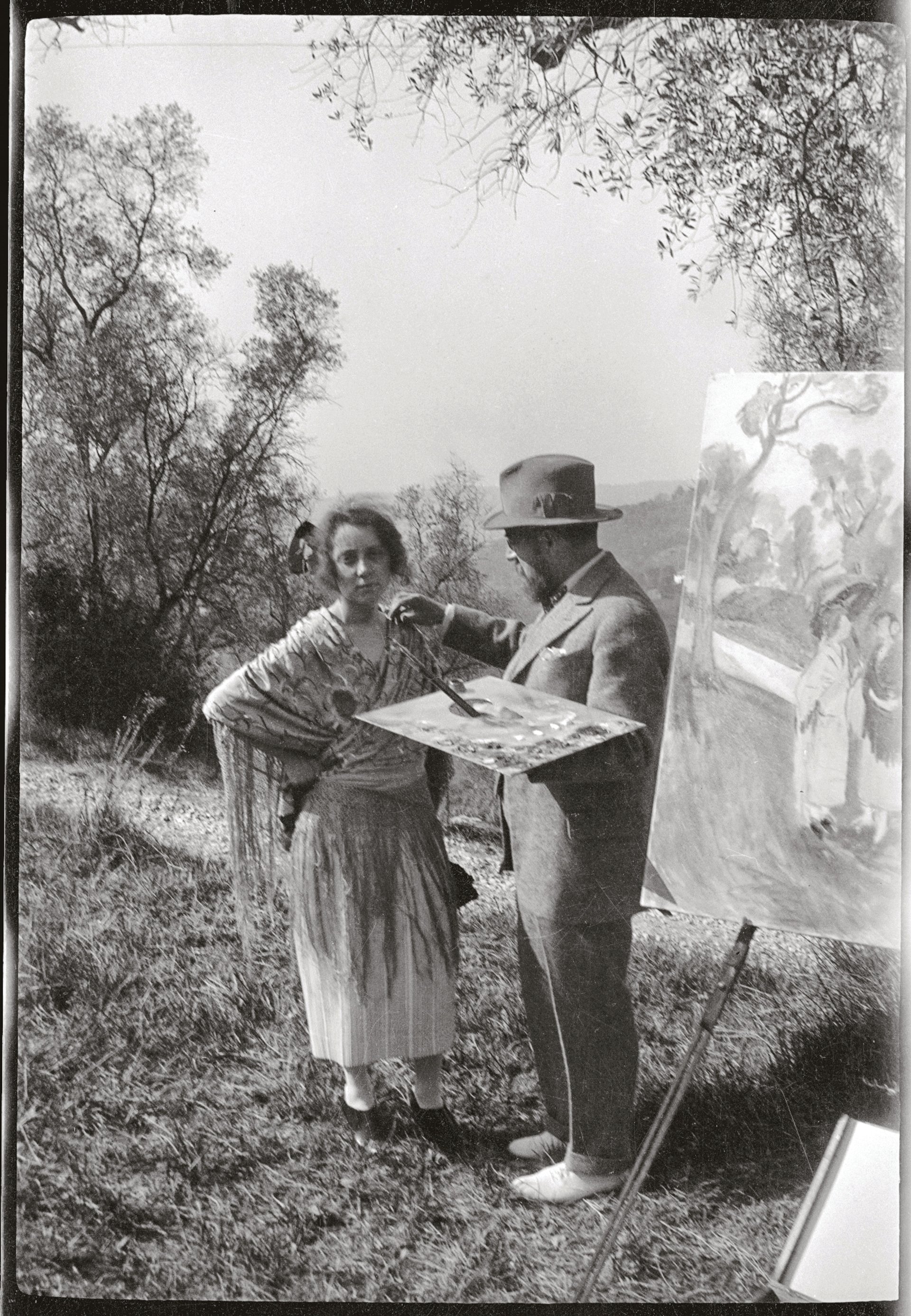

A 1921 photograph of Marguerite and her father as he worked on his painting Conversation sous les oliviers Archives Henri Matisse

The show—co-curated by Barat-Mabille, the conservator Isabelle Monod-Fontaine and the art historian Hélène de Talhouët—has been years in the making. Monod-Fontaine, now retired but formerly the deputy director of the Centre Pompidou, has curated multiple landmark Matisse exhibitions and had exceptional access to the artist’s personal archives in Issy-les-Moulineaux. She also knew Duthuit-Matisse, who passed away in 1982.

The exhibition is thus accompanied by a biography co-authored by Monod-Fontaine and de Talhouët, and by a comprehensive catalogue that includes those works for which they could not secure loans. Included in the show will be ubiquitous masterpieces, like Marguerite au chat noir (1910) as well as many works that have simply never been seen. “We’re showing a lot of drawings that have never been reproduced in books, so there really was no way of knowing them,” Barat-Mabille says.

Not everyone was initially convinced that a show of portraits wouldn’t be a little bit boring. “But actually, Matisse renews himself so often,” Barat-Mabille says. “Even the drawings—there are big ones, some done with marker pens, small things done really quickly in a sketchbook, others where a single line sums up the whole face. It is sumptuous, varied, alive.”

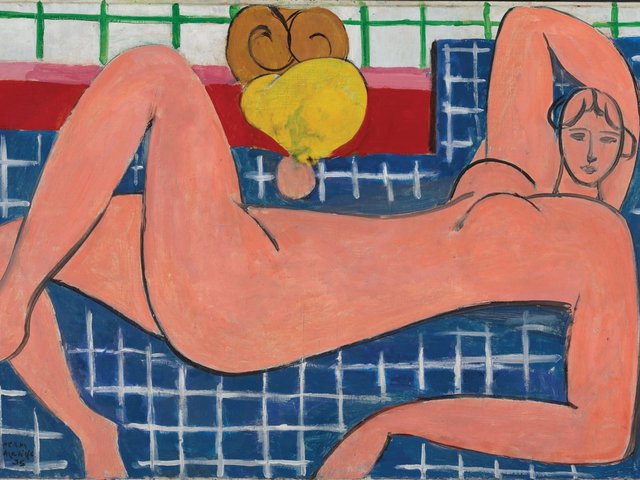

Tête blanche et rose (1914-15), a portrait by Matisse that demonstrates distinct Cubist tendencies © Centre Pompidou; MNAM-CCI; Dist. GrandPalaisRmn

The painted portraits, meanwhile, follow Matisse’s evolution. There is his Cubism-adjacent phase, with Tête blanche et rose (1914-15), and his Niçoise period, Fête des fleurs (1922) with all those scintillating colours, and Mediterranean light. “At one point, Matisse said to Marguerite: ‘I feel like this painting wants to take me elsewhere. Will you follow me in this new, slightly mad direction?’,” Barat-Mabille says. “The work becomes something very different to anything he’d done until then, with hard, harsh lines. And no doubt it was only with Marguerite that he could allow himself to explore in that way.”

Marguerite is the one person Matisse painted consistently, for decades. She starts out as a little girl wearing a black ribbon—Portrait de Marguerite (1906-07)—to hide the scar on her neck from a life-saving tracheotomy endured when she was seven. You may recognise her by that same ribbon as the woman in blue and white, in the foreground of Matisse’s masterpiece, Tea (1919). In Le Paravent mauresque (1921) she is the very picture of elegance, dressed all in white, leaning against the mantelpiece, framed by kaleidoscopic patterning.

Not long after this, in 1923, Marguerite married the Byzantine scholar Georges Duthuit, and for a long while no longer posed for her father. Instead, she became an agent, of sorts, wrangling collectors and dealers, hanging exhibitions and speaking her mind about her father’s work.

Marguerite, on the right, can be identified in Matisse's Tea (1919) by the ribbon she wore to hide a scar on her neck Museum Associates/LACMA; © 2020 Succession H. Matisse/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“There is a moment, when Matisse is in the south of France, when she says to him, ‘I think papa’s used up the light of Nice’,” Barat-Mabille says. Marguerite clearly thought her father needed to come back home for a break.

By the time Matisse drew his daughter in Vence in 1945, a gentle charcoal on now ageing paper, he was 76 years old. Marguerite was in her 50s. “I adore Matisse, I love his work. But what makes you love him even more,” Barat-Mabille says, “is discovering him as a father, in what really was, for its time, a very modern family. He was attentive, anxious for his children and for Marguerite in particular who was of such fragile health. [He was] a father who listened and encouraged and supported, which, for the early 20th century, wasn’t necessarily a given.”

• Matisse and Marguerite: Through Her Father’s Eyes, Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, 4 April-24 August