The Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) in New Haven, Connecticut, holds the largest collection of British art outside the UK. After a two-year closure amid a $16.5m project to conserve its Modernist Louis Kahn-designed building, the YCBA is ready to reopen on 29 March. Marking the occasion, the museum presents two exhibitions by influential British artists with ties to the seaside town of Margate: J.M.W. Turner and Tracey Emin.

Visitors familiar with Kahn’s design might be surprised to find the space free of apparent alterations. Indeed, conserving the acclaimed architect’s vision for his final project was a primary concern. Among the defining characteristics of the building, which opened in 1977 (three years after Kahn’s death), is its 224 skylights that provide natural lighting. Made of acrylic, these needed to be replaced with polycarbonate domes for climate resiliency and energy efficiency. Other exterior updates include a new liquid-membrane roof.

These renovations were undertaken by Knight Architecture, a New Haven-based firm that has helped with several restoration projects across Yale University’s campus. “Kahn’s building has held up incredibly well in the roughly 50 years since it was constructed, but it—like many other Modern designs—includes materials that are nearing the end of their lifespans,” George Knight tells The Art Newspaper. His firm became involved with the YCBA project in 2008 and has been carefully analysing the structure for more than 15 years.

The Yale Center for British Art's entrance court skylights Photo by Richard Caspole

It’s wonderfully organised, but Kahn’s design is difficult to work in, because its finishes are so unforgivingGeorge Knight, architect

“Dr. Amy Meyers, the long-time director of the museum from 2002 to 2019, felt that the building itself was the largest and most complex work of art in the collection,” Knight says. “It’s wonderfully organised, but Kahn’s design is difficult to work in, because its finishes are so unforgiving. For instance, the floors are travertine on top of concrete with wool carpeting, but there’s no underfloor area to route anything. Its interior environment doesn’t lend itself well to alterations. The inclusion of something seemingly simple like a wifi emitter proves to be a tempest in a teapot.”

How to conserve and adapt the space has long been a concern for the museum. In 2011, it published a conservation assessment, with recommended strategies to handle the building’s ongoing development. Written by the architects Peter Inskip and Stephen Gee with the museum’s former deputy director Constance Clement, the plan formed the basis of renovations that have been undertaken through the years, including for projects in 2015 and 2016.

Lighting the way

Using the conservation plan as a guide in the YCBA’s latest renovation, Knight Architecture focused on issues not covered in this first phase, including lighting improvements. “There have been several attempts to convert to more energy-efficient LEDs, but there was great concern about the colour temperature,” Knight says. “Lighting might be the most important—if ineffable—quality that one might want to conserve in a building.” Knight’s team successfully switched to LEDs and maintained the original lighting quality, while also updating nearly 7,000 linear feet of lighting track. Though some new fixtures were used, the architects were able to restore and rebuild many existing aluminium canisters—a signature feature of the interior—and retrofit them to use LEDs. “There was no aesthetic alteration, and we now have a safer system,” Knight says.

Paintings hang in the reinstalled galleries on the fourth floor of the Yale Center for British Art Photo by Michael Ipsen

Other renovations include updates to security measures, new carpeting and refurbished woodwork. Improvements were made to the light fittings below the skylight domes to diffuse sunlight and protect the works on view. “Our goal is the safekeeping of the collection, and these renovations will allow us to achieve this,” says Martina Droth, the YCBA’s new director since January, who previously worked for 16 years as a curator at the museum. “The updated lighting will also afford us greater flexibility than we’ve had in the past.”

Double bubble

With the project coming to fruition, the museum is looking forward to welcoming visitors back with two noteworthy exhibitions: J.M.W. Turner: Romance and Reality, a survey presenting the YCBA’s deep holdings of the influential British artist’s work that marks the 250th anniversary of his birth, and Tracey Emin: I Loved You Until The Morning.

“In a way, these shows stand for the bigger plan for the museum,” Droth says. “People know we have a lot of works by Turner, but we haven’t done a Turner show in more than 30 years. The time has come for us to reintroduce our treasures to new generations.”

Showing Emin and Turner concurrently, the museum hopes to highlight subtle connections between the artists’ practices, including their vigorous treatment of paint to create atmosphere and emotion, as well as their shared connection to Margate—Emin’s hometown and a frequent holiday spot for Turner.

A major Tracey Emin solo exhibition

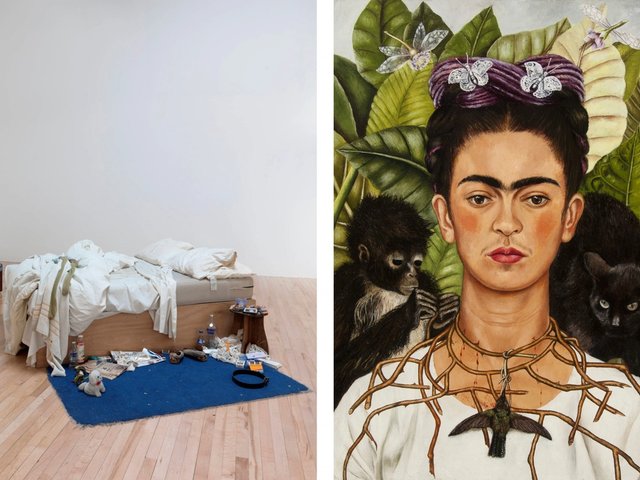

Emin’s exhibition demonstrates the YCBA’s commitment to engaging with contemporary art, and not just with the historical collections it has become known for. Though Emin has seen significant success in the UK since she rose to fame in the 1990s, the YCBA’s show is being described as her first major presentation in a North American museum, and one of few to highlight her painting practice. Indeed, she is better associated with the transgressive Young British Artists (YBAs) and her scandalous installations—such as Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 (1995), a tent featuring an appliquéd list of names.

The fact that Tracey Emin is not a tabloid persona in the US creates an opportunity for her painting to be evaluated and critically appraised outside of her fameMartina Droth, museum director

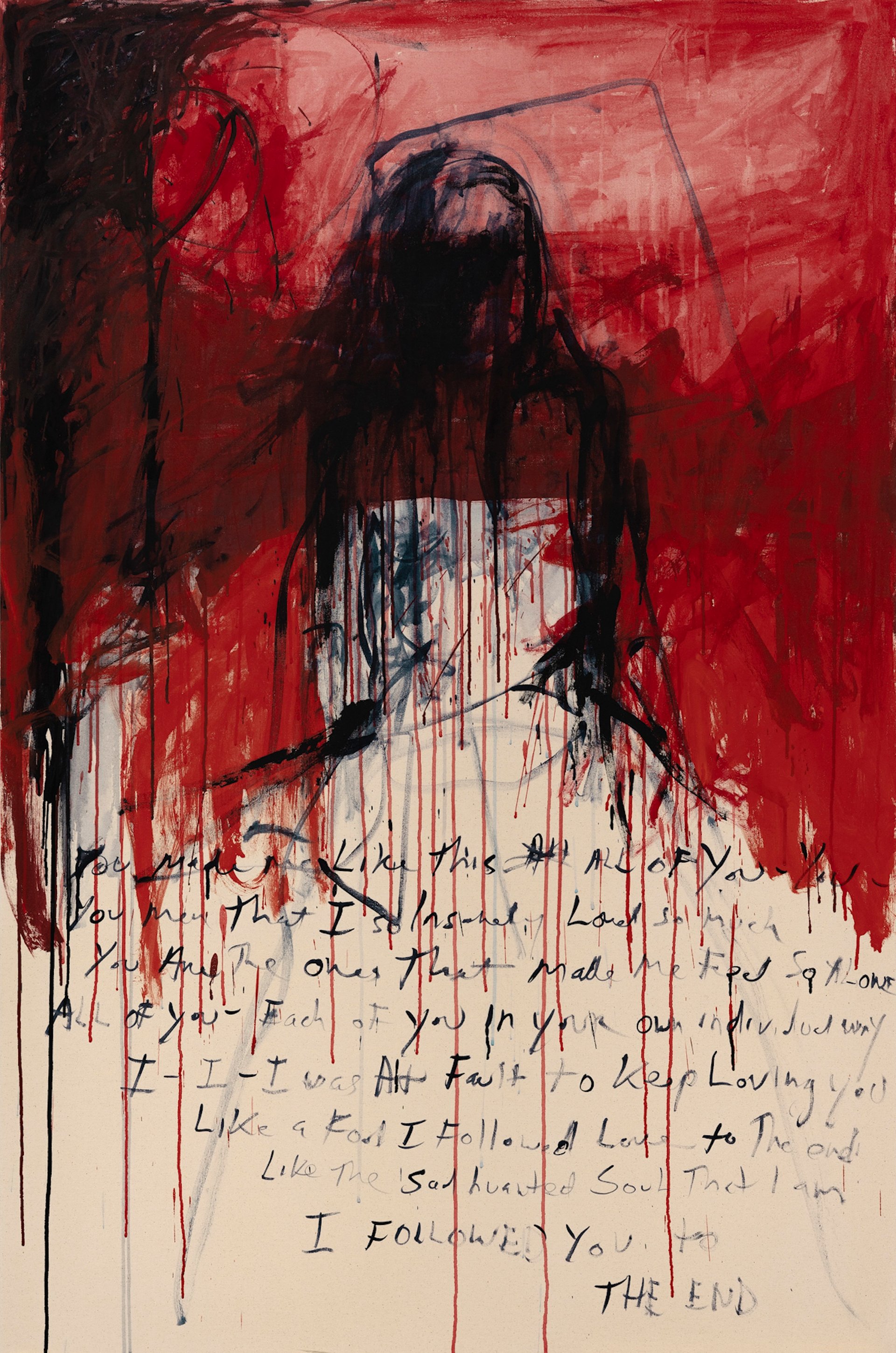

Tracey Emin, I Followed you to the end, 2024 © The Artist. Photo: Ollie Harrop, courtesy of Tracey Emin Studio

“Tracey is a household figure in the UK, but there are aspects of her art that I think even her British fans might not be aware of,” Droth says. “Her YBA identity is almost like an accretion that can be hard to shake off. There is a seriousness to what she does, in particular with painting, that people are only just beginning to recognise. The fact that she is not a tabloid persona in the US creates an opportunity for her painting to be evaluated and critically appraised outside of her fame.”

In addition to paintings, the show features work from Emin’s other disciplines, including a neon piece installed in the museum’s entrance, an area that had not previously been a priority for exhibiting art. Droth hopes the vibrant piece will invite visitors into the building and inspire curiosity—part of her vision to reconnect with audiences who might not be aware that the institution is open to the public. “It is difficult for us to present a friendly face,” she says. “Some people don’t know that we are a museum because of our name, or are intimidated because of our academic association. We can use our reopening to change this. No museum wants to be closed, but being closed means we also have the opportunity to celebrate a reopening. It’s a chance for us to extend as warm a welcome as possible.”

- J. M. W. Turner: Romance and Reality, 29 March-27 July; Tracey Emin: I Loved You Until the Morning, 29 March-August 10, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut