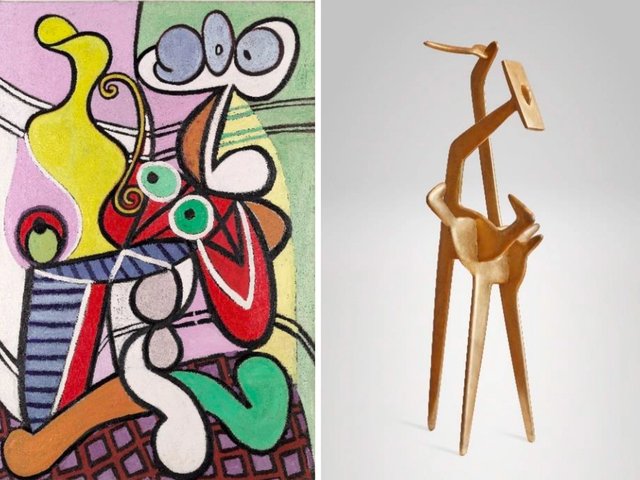

The most extensive exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso to open in Asia in decades has launched at the M+ museum in Hong Kong. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Series: Picasso for Asia—A Conversation includes more than 60 works dating from the late 1890s to the early 1970s by Picasso (1881–1973), alongside around 130 works by Asian and Asian-diasporic artists drawn from the M+ collection, including Isamu Noguchi, Luis Chan and Haegue Yang. The Picasso works are mainly drawn from the Musée national Picasso-Paris.

These are The Art Newspaper’s three key takeaways from the show.

Picasso snuck into China surreptitiously—via his dove imagery

After the Second World War, Picasso made his name in Communist China through his dove image (La Colombe), which illustrated posters promoting the World Peace Congress in Paris in 1949. Doryun Chong, the exhibition co-curator, said that Picasso’s art was not permitted to be shown in China as it was too “personal and domestic”—under Mao Zedong, art of the Socialist Realism school was the only type permitted in the post-war period.

But Picasso’s dove continued to permeate Chinese magazines in the 1950s. The exhibition curators have discovered numerous 20th-century Chinese publications that carry Picasso’s dove, including China Pictorial (1952) that shows the feathered beast flying above Beijing’s Forbidden City. Chinese postage stamps imprinted with the dove, stating “defend world peace” (1949), are also on display. These items are shown alongside two 1950s paintings by the Chinese artist Qi Baishi, which “enrich Picasso’s symbolism by adding Chinese wordplay”, says an exhibition caption.

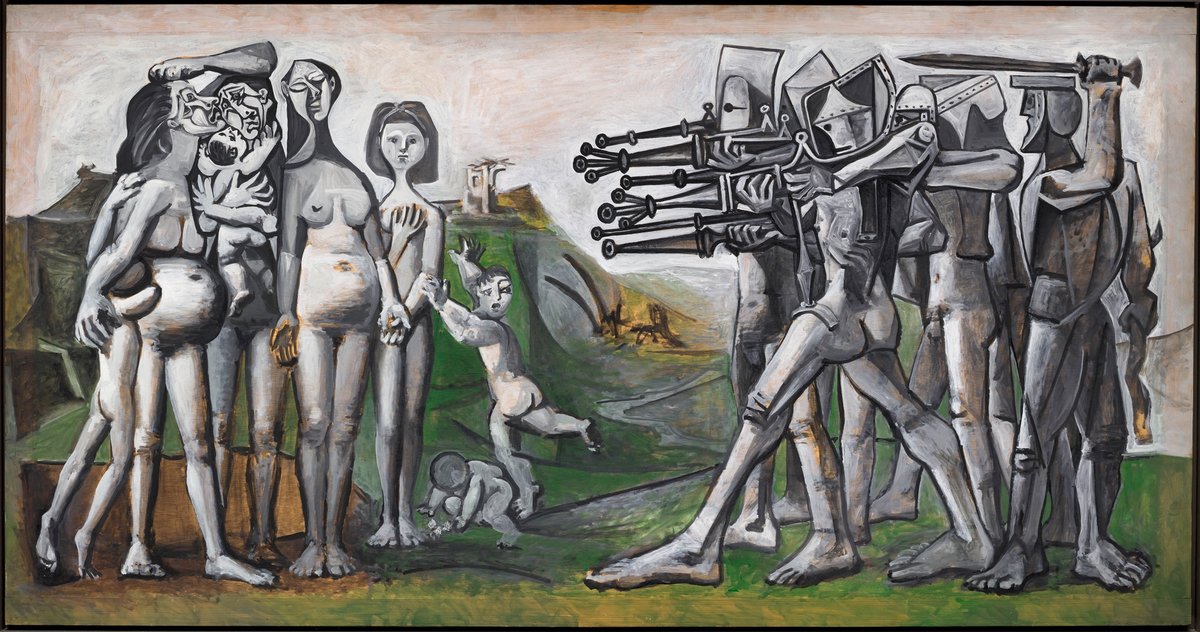

Picasso made few explicitly political paintings but Massacre in Korea bucks the trend

The exhibition ends with a searing anti-war piece, Massacre in Korea (1951) which depicts the horrors of the Korean War that broke out in June 1950, pitting Soviet Union-backed North Korea against the US-backed South Korea. Chong writes in the exhibition catalogue that “the two women at the far left of the composition wear expressions of extreme anguish and desolation, their visages reminiscent of the women’s faces in Guernica (1937)”.

The work was made for the Communist party but it was rejected by the leaders because, Chong said, “the aggressors were not aggressive enough and the victims were not victimised enough”. Writing about the work in 1980, the critic Kirsten Hoving Keen said: “[When] it was exhibited at the Salon de Mai in 1951, the canvas’s lack of propaganda detail provided an opportunity for party critics to chide the artist for not showing the obviously American nationality of the aggressors and for portraying an execution instead of the resistance of the Koreans.”

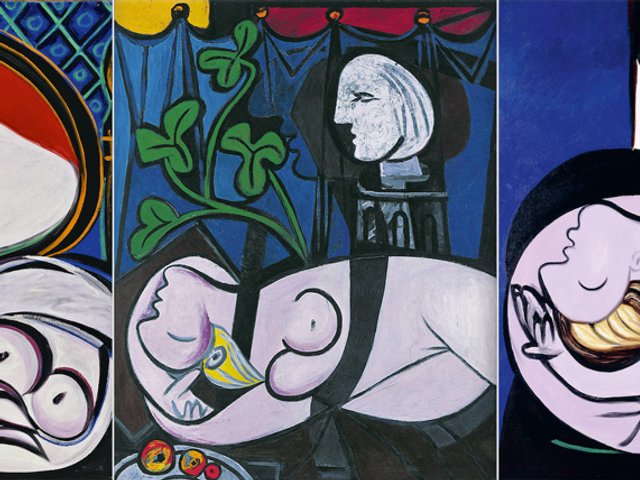

Picasso exhibitions today must acknowledge the artist’s misogyny

Picasso has been accused of abusing his muses and was 45 when he met Marie-Thérèse Walter, who was 17. “Anyone writing on Picasso today would be remiss not to recognise what we now know about the troubling aspects of his biography, especially his relationship with women who were also the main subjects of his art,” writes Chong.

A digital animation by the Indian artist Nalini Malani, Ballad of a Woman (2023), brings to the fore Picasso’s treatment of women. Facing three works by Picasso, including Portrait of Dora Maar (1937), the piece “is a powerful reminder of the attraction and cruelty that underpinned these [three] works”, says the wall caption. “[Malani’s] work magnifies the experiences of the disenfranchised and oppressed by layering motifs from folklore and classical literature with personal narratives,” writes Chong.

- The Hong Kong Jockey Club Series: Picasso for Asia—A Conversation, M+ Museum, Hong Kong, until 13 July