Egyptian, Middle Kingdom, carnelian falcon pendant jewellery

Around 2030-1650BC (earrings), around 2000-700BC (necklace)

€3,900 (earrings); €2,000 (necklace)

Kallos Gallery

In ancient Egyptian culture, amulets such as these were imbued with specific meanings relating to their form and believed to hold magical properties when worn; they were even woven into mummy wrappings to protect the dead in the afterlife. These carnelian gemstones are carved into the shape of falcons, evoking Horus, the god of sky, war, hunting and kingship who was commonly associated with healing and protection. A similar example dated to the Middle Kingdom can be found in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Kallos, a London gallery specialising in ancient art, has set three falcon amulets, each measuring around 1cm long, into modern 18-carat gold earrings and a chain so they “can continue to be worn and enjoyed every day just as they would have been in the ancient world”, says Hayley McCole, a gallery specialist. “Although nearly 4,000 years old, our Egyptian carnelian falcon amulets are in excellent condition. This is testament to the incredible skill of ancient Egyptian artists who worked with semi-precious stones to create enduring and beautiful miniature works of art,” she adds.

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian) and Girolamo Dente, Madonna and Child with St Mary Magdalene (Around 1555-60) Courtesy of Trinity Fine Art

Tiziano Vecellio (Titian) and Girolamo Dente, Madonna and Child with St Mary Magdalene

Around 1555-60

In the region of €8m

Trinity Fine Art

Held in private collections for more than two centuries, this painting by the Italian Renaissance master Titian and his collaborator Girolamo Dente has not been seen in public since it was sold at Christie’s in 1937. Since resurfacing, the painting has undergone X-ray analysis that revealed that some original elements of the composition were removed—such as a window on the left-hand side and a sunburst halo above the child—while others were added, including the child’s coral necklace. Mary Magdalene was initially painted as a male figure with a beard before being reworked.

“One is tempted to think that the picture may have been conceived, and largely painted, for someone who died before it was completed, or who may never have collected it from the artist,” writes the Renaissance art historian Enrico Maria Dal Pozzolo in the catalogue for the painting. “At that point, it remained in his workshop until he decided, a few years later, to turn the figure into St Mary Magdalene, delegating the change to an assistant, whom we can almost certainly identify as Girolamo Dente.” The gallery says the picture’s “excellent condition” and the “superb quality of the brushwork” gives it “the edge over other versions of the same subject in some of the world’s leading museums”, such as the State Hermitage Museum and the Gallerie degli Uffizi.

Ben Enwonwu, Ebony (1965) Courtesy of Tafeta

Ben Enwonwu, Ebony (1965)

£60,000

Tafeta

“See in Venice, buy at Maastricht” is the adage being put to the test by the London-based gallery Tafeta, which specialises in 20th-century and contemporary African art. Seven of the artists featured in its Tefaf stand this year were represented in Adriano Pedrosa’s main exhibition of the 2024 Venice Biennale, Foreigners Everywhere. The Biennale “represents a powerful endorsement of work from this era of African artistic production and offers the gallery an unprecedented opportunity to platform their individual practices to a seasoned collector base,” Tafeta says in a press statement.

One such artist is Ben Enwonwu, whose 1962 painting The Dancer appeared in Venice. Celebrated for his figurative paintings and sculptures, the Nigerian Modernist is best known for his works exploring the dancer theme. Enwonwu began his Africa Dances series during his studies in London in the 1940s, inspired by Geoffrey Gorer’s book of the same name, which critiqued colonial rule in Africa and its negative impact on traditional life. Capturing “the serpentine movement of a gracefully dancing figure”, this gouache and watercolour work on paper “exemplifies Enwonwu’s Negritude style, which he developed in the late 1940s and 1950s”, says the art historian Alayo Akinkugbe.

Montelupo Gothic majolica albarello (15th century) Angelo Plantamura

Montelupo Gothic majolica albarello

15th century, Florentine area

£85,000

Amir Mohtashemi

This albarello—an earthenware jar often used by apothecaries to store medicines—is one of a rare group known as Italo-Moresques, thought to originate in 15th-century Siena. Only 25 albarelli are known to feature this kind of blue-and-white pseudo-Kufic decoration, an imitation of Arabic calligraphy created by European artists influenced by Islamic design. This is one of the largest, at 33.5cm tall. Most other examples are held in major museums throughout the world.

“Though the art of Renaissance Italy is more likely to conjure up images of altarpieces than it is of the Islamic world, the pseudo-Kufic decoration and form likely derive from Syrian prototypes, known in 15th-century inventories as ‘albaregli damaschini’,” says Manon Lever, a researcher at Amir Mohtashemi. “This group is dated by an appearance of an Italo-Moresque albarello in an altarpiece from around 1453 by Giovanni di Paolo, suggesting that Islamic-inspired art was commonplace enough not to draw attention in a piece of Catholic art.”

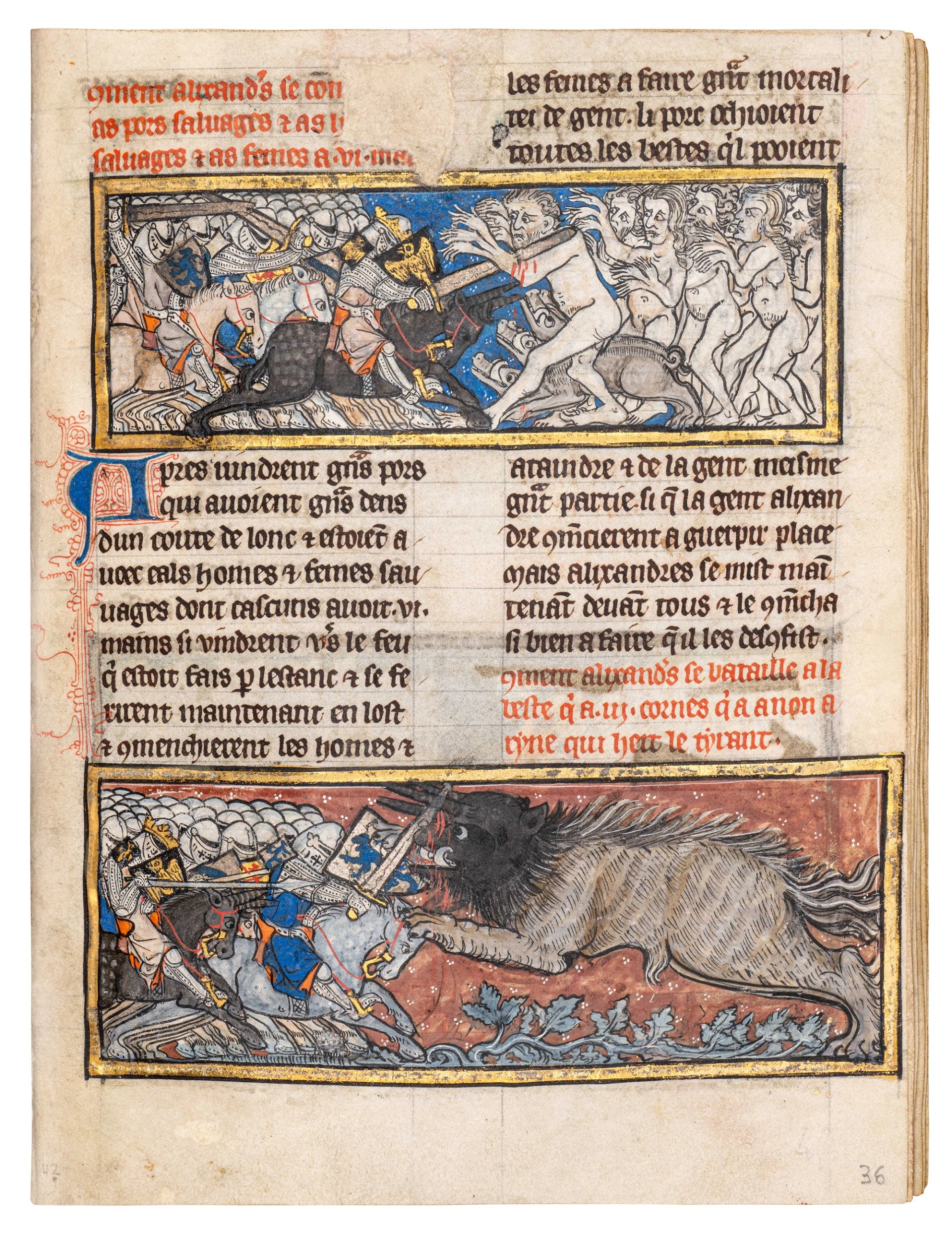

Roman d’Alexandre en prose manuscript (around 1290-1300) Courtesy of Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books, Basel

Roman d’Alexandre en prose manuscript

Around 1290-1300

Sfr3.4m (£3m)

Dr Jörn Günther Rare Books

One of only 18 surviving copies of Roman d’Alexandre en prose, this more than 700-year-old illuminated manuscript tells the tale of the ancient Macedonian king Alexander the Great. Although Alexander is revered in military history for never losing a battle, the codex greatly embellishes his real-life conquests with a host of fantastical creatures and miraculous deeds. The unknown illuminator imaginatively depicts scenes ranging from giants and unicorns to Alexander’s deep-sea explorations in a glass submarine. Written in Old French on vellum, this manuscript is one of only four known copies of the story’s second version, made after 1252. The other three are held in the British Library, the Royal Library of Belgium and the Berlin State Library.

Research by the Medieval art historian Alison Stones has identified the manuscript with a group produced in the region of Reims in Champagne or Ypres in Flanders.