The very first work Tacita Dean saw of Cy Twombly’s was a collage and watercolour on paper, Pan (1975), that greeted visitors to the US artist’s retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1987.

Dean remembers the moment clearly. She was an undergraduate at Falmouth School of Art. A lecturer had suggested she look at this artist called Cy Twombly, who at that point was not that well known in the UK. She got on a train to London, walked into the gallery, and everything changed. Dean would experience a similar bolt of lightning seeing the Marcel Broodthaers retrospective in Paris a few years later, in 1991. Both were instances of, as she puts it, “finding your bedfellows in life”—a feeling she describes, three decades on, as “100% intact”.

“Copying his words, his handwriting, was my way of trying to get closer to him that night”Tacita Dean

That lifelong devotion undergirds a new artist book Dean has made, Why Cy. It is the result of a night she spent alone with Twombly’s works at the Menil Collection in Houston last year and coincides with her show there, Tacita Dean: Blind Folly (until 19 April).

The idea of pulling an all-nighter in the museum’s Cy Twombly Gallery came to Dean after she had spent a month attempting to make something in relation to the works it contains. “When you sit in front of a work of art, your mind wanders. I wanted to try and catch those thoughts. But as soon as my mind knew it was trying to catch itself, it stopped performing. I became too aware of it. I suddenly realised I needed a framework, a constraint.”

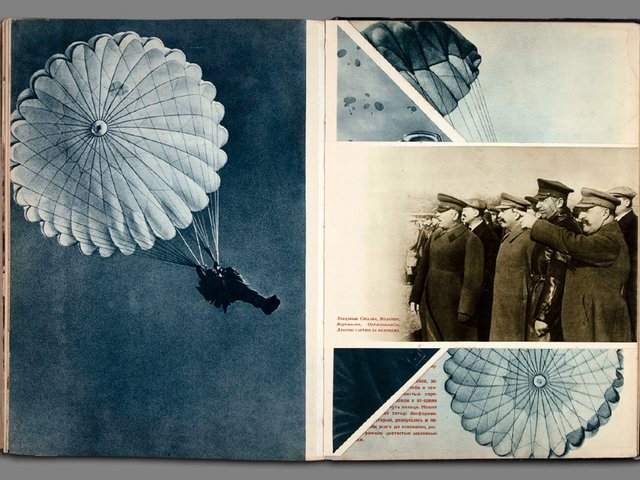

Tacita Dean’s latest book comprises a series of close-up photographs she took of Cy Twombly’s text-based works Photo courtesy of the artist and MACK

The museum agreed to lock her in for the night. She wandered around with her camera and her notebook, the finite amount of time of a single night, like a roll of film, forcing her to make decisions.

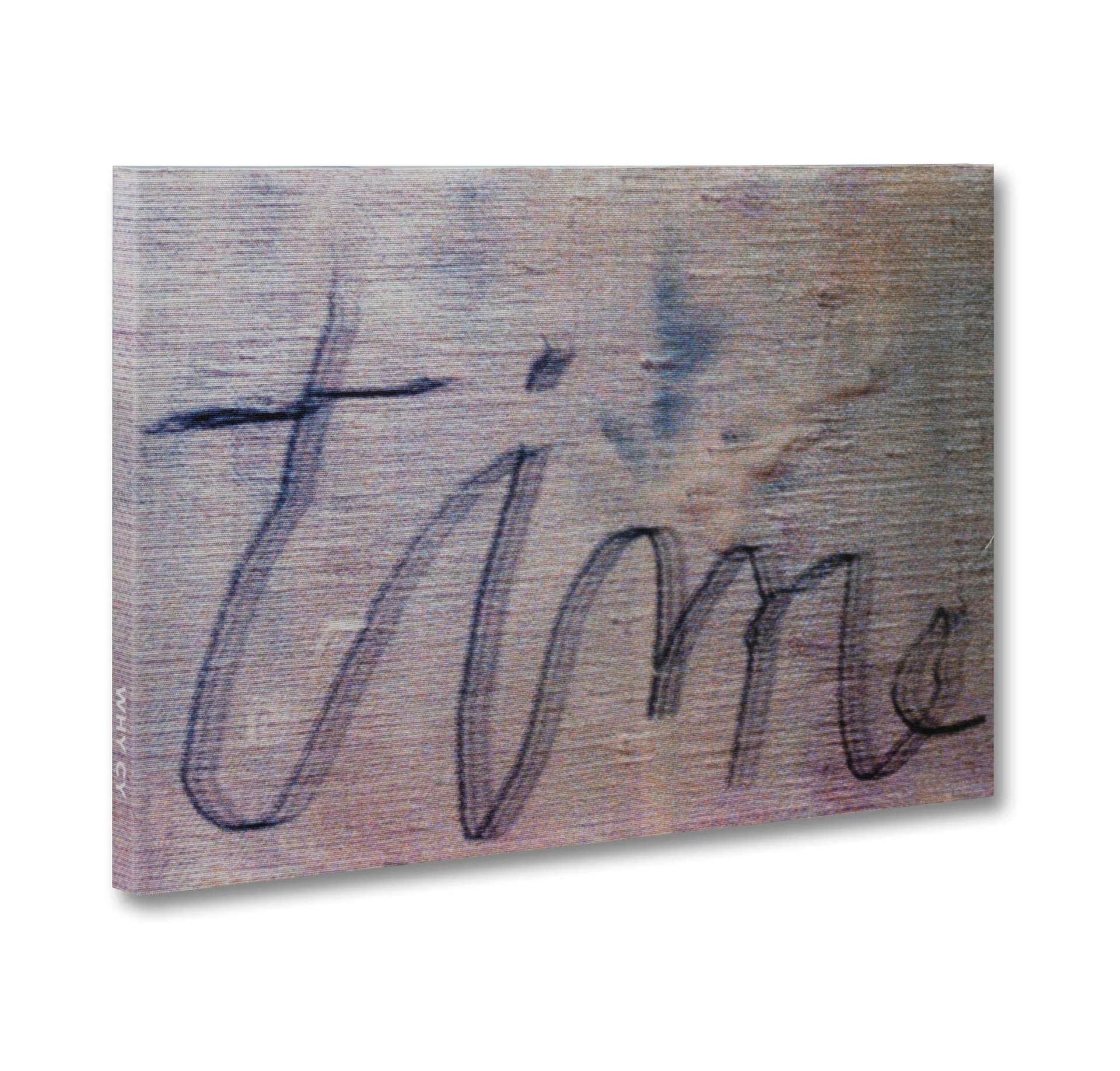

The resulting book, like other artist books she has made, features a work of art on the cover and includes a further 99 photographs taken during those sleepless hours. Also included is a booklet of her notes, some typed up, others reproduced as handwritten entries.

“Cy used to write in darkness in the war, and he always said that that relates to why his writing has that slight ghostly quality to it, a blindness,” Dean says. “But I was not trying to do that at all. I was writing for myself. I was also trying to copy his writing in my notebook, which is what he used to do too: copy Old Masters, as a way to trigger ideas.”

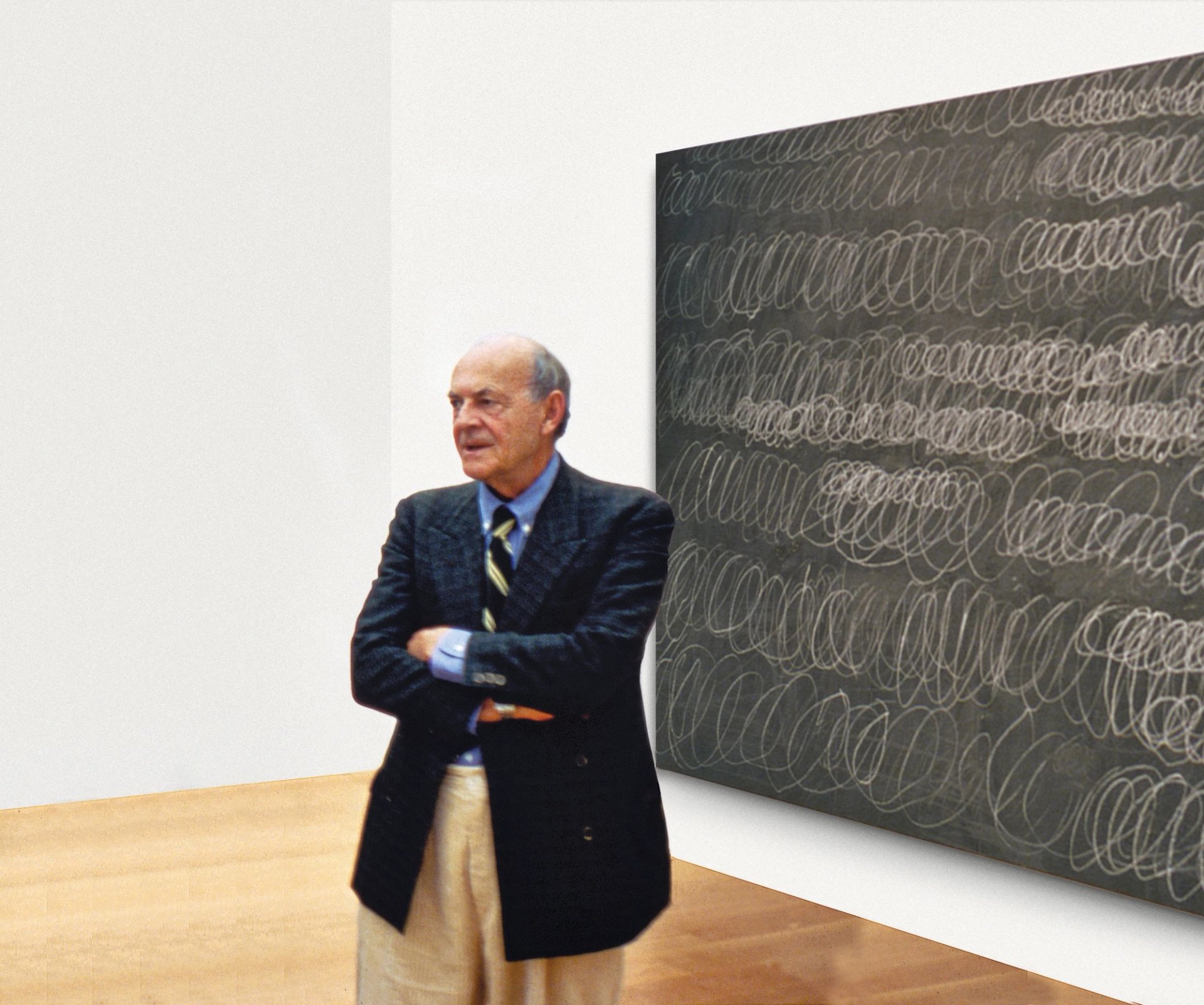

Twombly at the opening of the Cy Twombly Gallery at the Menil Collection in 1995 Photo: Hickey-Robertson Courtesy of the Menil Collection

Some of Dean’s notes are pretty funny. “What is Maat?” she writes in her casual cursive beneath a drawing that appears to spell out that word. “I guess I’ll have to consult that godawful book.” Further on she references hating “the transcription book”: the six-volume publication produced in 2022, in which the art historian Thierry Greub painstakingly transcribed all the written notes and literary fragments found across Twombly’s oeuvre. Dean objects to how this denies the mystery inherent to the artist’s use of language.

To her mind, she and he use words in the same way: as a means by which to make connections, with any erasure then becoming part of the image. “Cy would bring it back if he wanted to, and if he didn’t want to, he’d let it be submerged.” Dean likens that forensic art historical transcription to an archaeologist rummaging around in the soil.

This insider understanding of how Twombly used words in drawing has preoccupied Dean from the outset. When the curator Lynne Cooke invited her to take part in Dia’s Artists on Artists lecture series in 2003, she chose Twombly and used, as base material, the art school thesis she had written, which delved into handwriting and erasure and the connection to the classical past.

Tacita Dean's new book Why Cy is published by Mack

“I got myself into such a mess in that lecture,” she says, “that I was always slightly mortified by it.” In the recording of the talk, you hear a slight tremor in her voice as she begins: “Cy Twombly is not an easy artist to have chosen: his paintings and sculptures are, as everyone knows, ineffably beautiful and therefore make everybody a bit speechless. Language flounders…”

Dean would finally get to meet Twombly at the opening of his 2007 show at Gagosian in Rome. He was then in his 80s. A friend of Dean’s had saved several cards from her Dia talk, on which was printed “Tacita Dean on Cy Twombly”. She said she would love for Twombly to write her name —“silent” in Latin—on them. And so, the first thing Dean heard Twombly say is “Nicola”, addressing his partner, “Have you got a pen?” He then wrote “Tacita Tacita Tacita Cy Cy Cy” on those three cards. Dean has kept them safe ever since.

Recently, she realised he had made a work called Tacitus: one of the embossed lithographs in his 1975-76 portfolio, Six Latin Writers and Poets, that features the word loosely written in enticing slanted capitals, like the title on a frontispiece.

Dean came away from her overnight stay at the Menil with a whole book of drawings, some more personal than others. “Copying his words, his handwriting, was my way of trying to get closer to him that night.”

• Tacita Dean, Why Cy, Mack, 96pp, £75 (hb)