To witness the launch of the media artist Refik Anadol’s AI-powered generative art installation, Living Architecture: Gehry, at the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao—projected on the towering interior walls of Frank Gehry’s architectural masterpiece as part of the exhibition in situ: Refik Anadol—is to be reminded of the long history of architect’s visionary dreams.

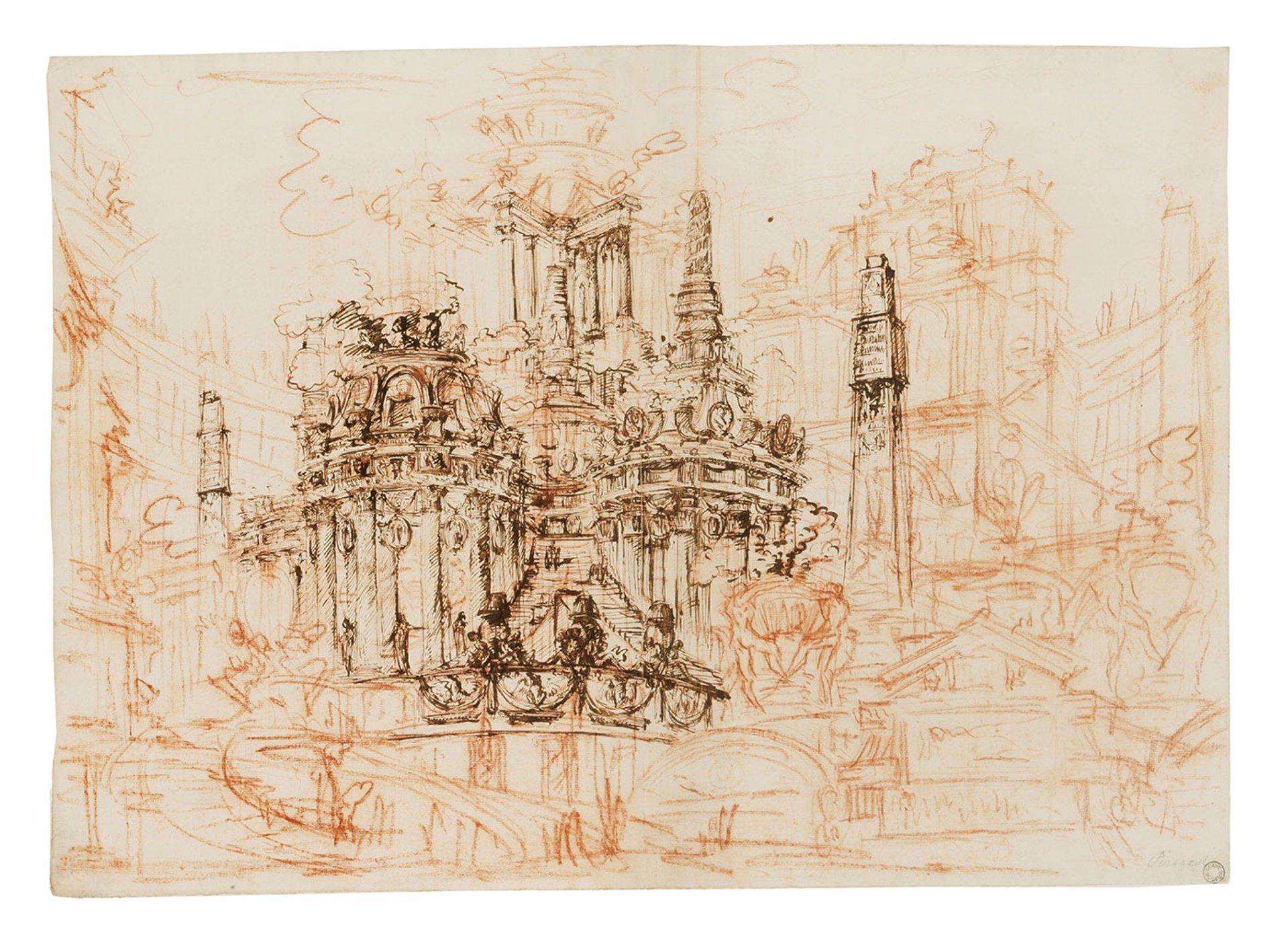

It is a history that ranges from the weightless Baroque of Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s multi-level "capricci"; to the monumental spheres and pyramids of the 18th-century visionaries Claude-Nicolas Ledoux and Etienne-Louis Boullée; and to the neo-Classicist CR Cockerell’s sublime The Professor’s Dream (1848), a receding vision, covering Ancient Egypt to High Renaissance, heaping temple upon tower upon ghostly dome. And of course, there is M.C. Escher’s intricately mind-bending visual puzzles and Frank Lloyd Wright’s unbuilt but uncompromising mile-high skyscraper.

A long art history of architectural dreams: Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Unfinished capriccio, about 1755. The drawing is on loan from the Sir John Soane Museum, in London, for the exhibition Towering Dreams: Extraordinary Architectural Drawings (15 March – 31 August) at Compton Verney, Warwickshire ©Sir John Soane’s Museum, London

Anadol has added new dreams to that gallery, and reminded the viewer of the sheer sculptural verve of Gehry’s buildings. By taking archival data supplied by the 96-year-old Canadian-born Los Angeles-based architect, covering 65 years of work—as well as a mass of ethically accessed open-source architectural images—and combining them with data in Anadol’s own large nature model, the artist has created a new large architecture model, and from that a six-chapter artificial intelligence (AI) experience. The chapter structure expresses Anadol’s commitment to showing his process as an artist, one that he demonstrated a year ago in his exhibition Echoes of the Earth: Living Archive at Serpentine Galleries, London, where he used a data process wall to show radical clarity on the raw data sources and functional make-up of his large nature model.

Living Architecture: Gehry, Refik Anadol's new work at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao © Refik Anadol, Bilbao 2025

In situ: Refik Anadol—curated by the Guggenheim Bilbao’s Lekha Hileman Waitoller as the first of a sequence of site-specific “in situ” shows planned by the museum—presents Living Architecture: Gehry in the 16-metre-tall Room 208. There is a separate, smaller, “education room” where the work’s process is laid out for visitors.

The chapters follow a procedural and narrative sequence, starting with the compiling of architectural data in a “memory space”, before the plotting of patterns in that data. This is followed by a stage of human-machine collaboration before the emergence of the large architectural model, which transforms Gehry’s work in boundary-pushing directions. The concluding chapters are an AI hallucination that produces abstracted visions, and a return to the world of architecture where the AI generates architectural dreams in real time.

How Anadol works with scale and space

Anadol’s packed sequence of AI installations around the globe over the past two years has shown careful consideration of the shape and scale of the space to hand. From Unsupervised — Machine Hallucinations in the airy Gund Lobby at the Museum of Modern Art, New York (2022-2023), to the massive external projection at Sphere in Las Vegas (September 2023), to the intimate brick, cloister-like, space of Serpentine North (February to April 2024), and the expansive main auditorium for the opening concerts of the World Economic Forum summit at Davos (2024 and 2025). That adaptation to space is centred on Anadol’s own long-standing love of architecture, which was given public expression in Living Architecture: Casa Batlló (2022), a media art piece projected onto Antonio Gaudí’s celebrated 1906 house in Barcelona. Anadol created the work by using AI to model a dataset based on millions of publicly available images and documents relating to the house.

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, and the nature and scale of its larger spaces—which have an assertive presence that tends to challenge even the grandest, most robust, of physical art—feel tailor-made to allow Anadol’s AI dreams to expand and flourish. It is a space, as Anadol tells The Art Newspaper, where “the room becomes the canvas”, and where the experience goes “beyond the screen”. The algorithm devised to generate the installation, matching the building’s serpentine contours, is “very different”, Anadol says. “It uses the building as the canvas. The whole thing is attached to the building, from ceiling to floor…following the frame, following every curve.”

Refik Anadol: "The whole thing is attached to the building, from ceiling to floor … following every curve" Photograph: Efsun Erkiliç

“Look at this, how nature and architecture connect,” Anadol says, as 50 projectors channel a surging visual narrative onto the walls. The AI model is iterating, or generating, continuously, with never the same sequence of images. While Anadol speaks, Efsun Erkeliç, co-founder and executive producer of Refik Anadol Studio and also Anadol’s wife, walks towards the apex of Room 208, shaped like the forward section of an empty supertanker’s hull.

As she approaches the space’s furthest point, she is dwarfed by the size of the moving images from Dreams, the final chapter of the installation. A dazzlingly white architectural-cum-mycelial creation—half cliff, half giant fungal gills—eases majestically up the elevation, before the visual narrative cuts to a looming honeycomb structure with saturated-green shrubbery pushing through its openings.

That sequence is replaced in turn by fantastical, gridded, industrial-flavoured monochrome sketches—an AI meditation, perhaps, on early-period Gehry, who started designing buildings in the 1950s when Frank Lloyd Wright was still at his drawing board and Philip Johnson at the pinnacle of his New York starchitect celebrity—which take on an increasingly Escher-like quality as they are spooled and mirrored across the gallery walls.

It is a multi-sensory experience, in which the AI is prompted to action by an immersive soundscape, composed by Kerim Karaoglu, and one with an olfactory element: a special, AI-conceived, scent for releasing into the space, in a development of a procedure demonstrated at the 2024 Serpentine show. Ryan Zurrer, one of the world’s leading collectors and supporters of digital art, and founder of the collective 1OF1 (a partner of the Bilbao exhibition), describes In situ: Refik Anadol in posts on Instagram and X, as “almost certainly the most complex and technically sophisticated projection of all time, especially given the asymmetric nature of the gallery & the evolving nature of the work”.

Anadol tells The Art Newspaper that in the year he has spent preparing the piece for Bilbao, he has been “dreaming so much” on Gehry’s life and legacy. Thinking on Gehry’s impact on the world, one that makes Living Architecture: Gehry a “very special piece”. One that, Anadol says, is “needed in this time of heated dialogue”. At Guggenheim Bilbao he is intent on honouring the architect’s “positive impact”, as well as the achievements of other great artists—Richard Serra, Sol LeWitt among them—who are part of the museum’s history as a cultural landmark that has transformed a city’s image and fortunes in the years since its opening in 1997.

Anadol and ethical AI

Anadol is, as ever, on a mission for the preservation and enhancement of the global environment. At the World Economic Forum in January, his Large Nature Model: Glacier was a warning about the threat to the world’s glaciers, and especially those of Antarctica. The Gehry installation is hosted, he says, on Google Cloud—one of the exhibition’s collaborators—in the Netherlands, where the tech giant has a sustainable data centre powered by wind and sun. And the data used in the large architectural model are all either open source, provided by Gehry’s practice, captured by the Refik Anadol Studio, or accessed from the leading natural history institutions who opened their collections for the creation of the earlier large nature model.

With his global profile, Anadol raises awareness of digital art, of artists working with artificial intelligence, and with the artist’s role in society. As Zurrer put it last week, Anadol has an “ability to inspire millions and make it all look so seamless”. It is an ability, Zurrer wrote on social media following the show’s opening on 7 March, that “stands on the shoulders of his exceptional team”, of whom Zurrer singled out Erkeliç and Dogukan Yesilcimen, the studio’s head of art relations.

In the recent sale of AI art at Christie’s New York, Anadol’s Machine Hallucinations – ISS Dreams – A (2021) was the top lot, selling for $277,200 (with fees). It is part of the series Machine Hallucinations, and uses satellite imagery of Earth and 1.2m images taken by the International Space Station. That online auction earned headlines when an open letter signed by thousands of artists and creative people asked Christie’s to cancel the sale, saying it incentivised the “mass theft of human artists’ work” because of the behaviour of large companies who built text-to-image AI models by scraping the internet.

Living Architecture: Gehry, Refik Anadol's new work at the Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao © Refik Anadol, Bilbao 2025

“I completely agree with them,” Anadol tells The Art Newspaper, talking of the open letter’s concern for the misuse of copyright material, but, as when the letter was published in early February, he points out that he has built his own AI models and always with ethically sourced, or self-generated, data. The ISS Dreams piece, he says, was created using an AI model trained on publicly available datasets from Nasa. It is an irony not lost on Anadol that he, like so many artists involved in the sale—including the semi-autonomous AI artist Botto, and the duo Mat Dryhurst and Holly Herndon—have been the ones leading a sophisticated and useful public debate on how artists’ work is owned and how it is used as training data by big AI companies.

Anadol offers a “thinking brush”—to dream with

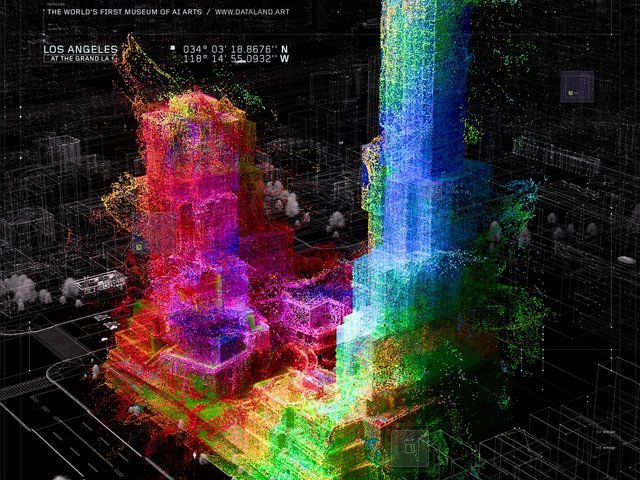

For Anadol it has been a full first quarter of the year, with the prospect of the opening of his studio’s Dataland museum of AI art in Los Angeles—possibly before the end of 2025, as the city works to recover from the devastating impact of the recent Palisades and Eaton wildfires—where Anadol and Erkeliç set up their studio in 2014. The museum will be based in a flagship downtown location at the Gehry-designed development The Grand LA, across South Grand Avenue from Walt Disney Hall performing arts centre, another Gehry edifice, making it likewise a neighbour of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (Moca) and the Broad museum. All these institutions, Anadol says, have given Dataland “a very warm welcome and warm support” to the city’s museum quarter.

With Living Architecture: Gehry and the large architectural model it is based on, Anadol says, he is offering the world a “thinking brush”. “We are in this era,” he says, “where we can train our own AI models with our own data. It's not so different to making our own pigment and our own gestures on a canvas.” Asked how working with AI for the past decade has changed his attitude to what art is, he says it has caused him to ask “What is reality?”

Anadol says that it is now possible to talk of a thinking brush and of a coming “generative reality”, in reference to algorithm-powered generative art. It is something, he says, that is “becoming profoundly real while we question what is reality”. And, referring to his concept of a thinking brush, he says that one of the reasons he loves working with the large nature model and now the large architecture model is that he can hand it to his colleagues and collaborators and say, “Here's the brush. Do you want to dream?”

- In situ: Refik Anadol , Guggenheim Museum Bilbao until 19 October.