There are few lonelier pictures than Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893), with its protagonist wailing beneath a fire-orange sky, or Melancholy (1891), depicting a man sat mournfully by a shoreline. However, a forthcoming exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in London will show an entirely different side to the work of the Norwegian Expressionist, bringing to the fore the lively network of family, friends and patrons he painted throughout his life.

Edvard Munch Portraits is the first UK show to focus on Munch’s portraiture, defined as work he made “from a particular person in the moment”, explains its curator Alison Smith. It explores the artist’s family life and time spent in Bohemian circles in Kristiania (present-day Oslo), Paris and Berlin, along with a further spell in Germany and his later years after returning to Norway.

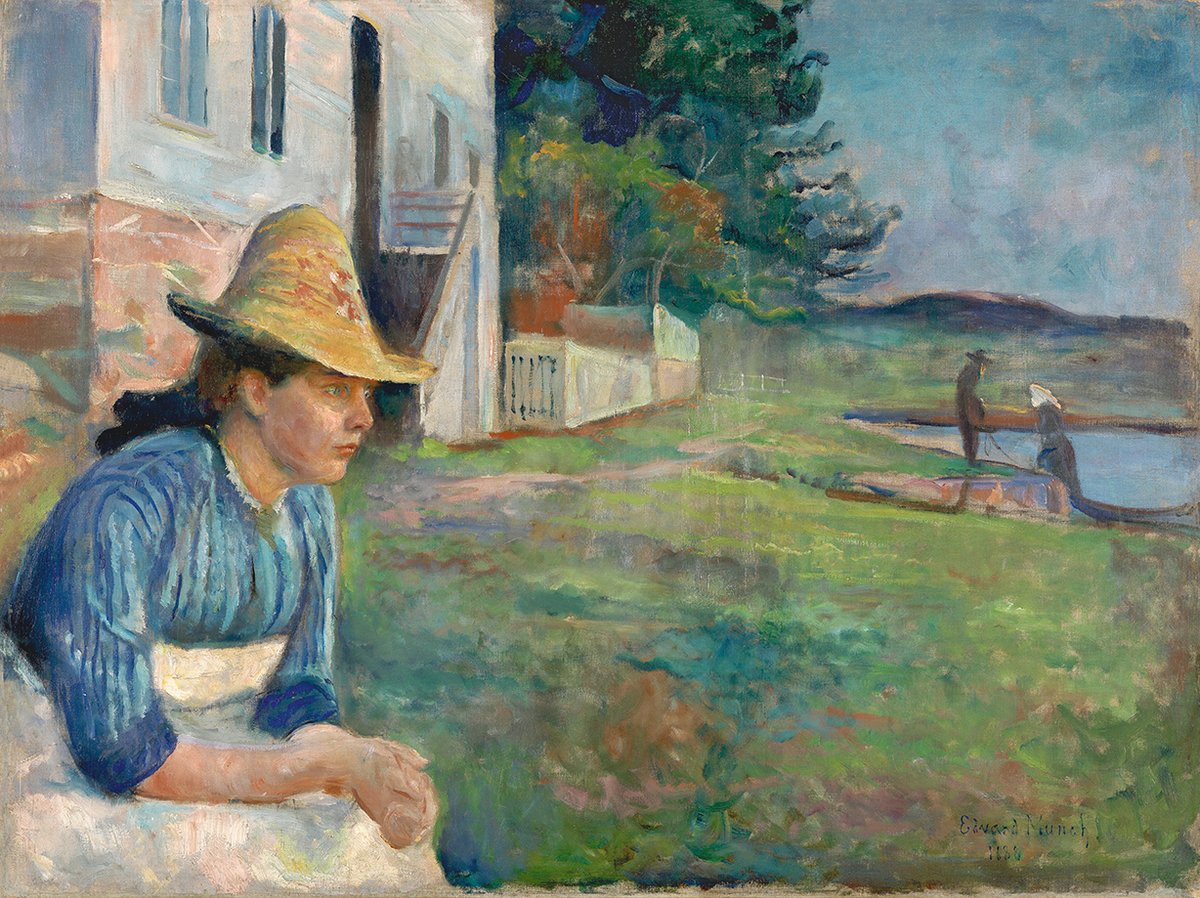

The family pictures speak to a challenging period for Munch, who lost his mother and elder sister to tuberculosis before he started to paint in earnest, but also one of intense artistic progress. There are brooding, naturalistic renderings of figures such as his aunt Karen, dressed in black, her eyes cast down. Evening (1888) depicts another sister, Laura, gazing out across a grassy field, and shows him beginning to engage with aesthetics that would define his later practice. “You can see he’s been looking at French artists, and he suggests the influence of Japanese art by squeezing Laura to the side,” Smith says. “Her vacant gaze out of the picture, meanwhile, anticipates Melancholy.”

That’s what you get for having your portrait done by a great artist—you look more like yourself than you really areWalther Rathenau, industrialist and sitter for Munch

Behind the mask

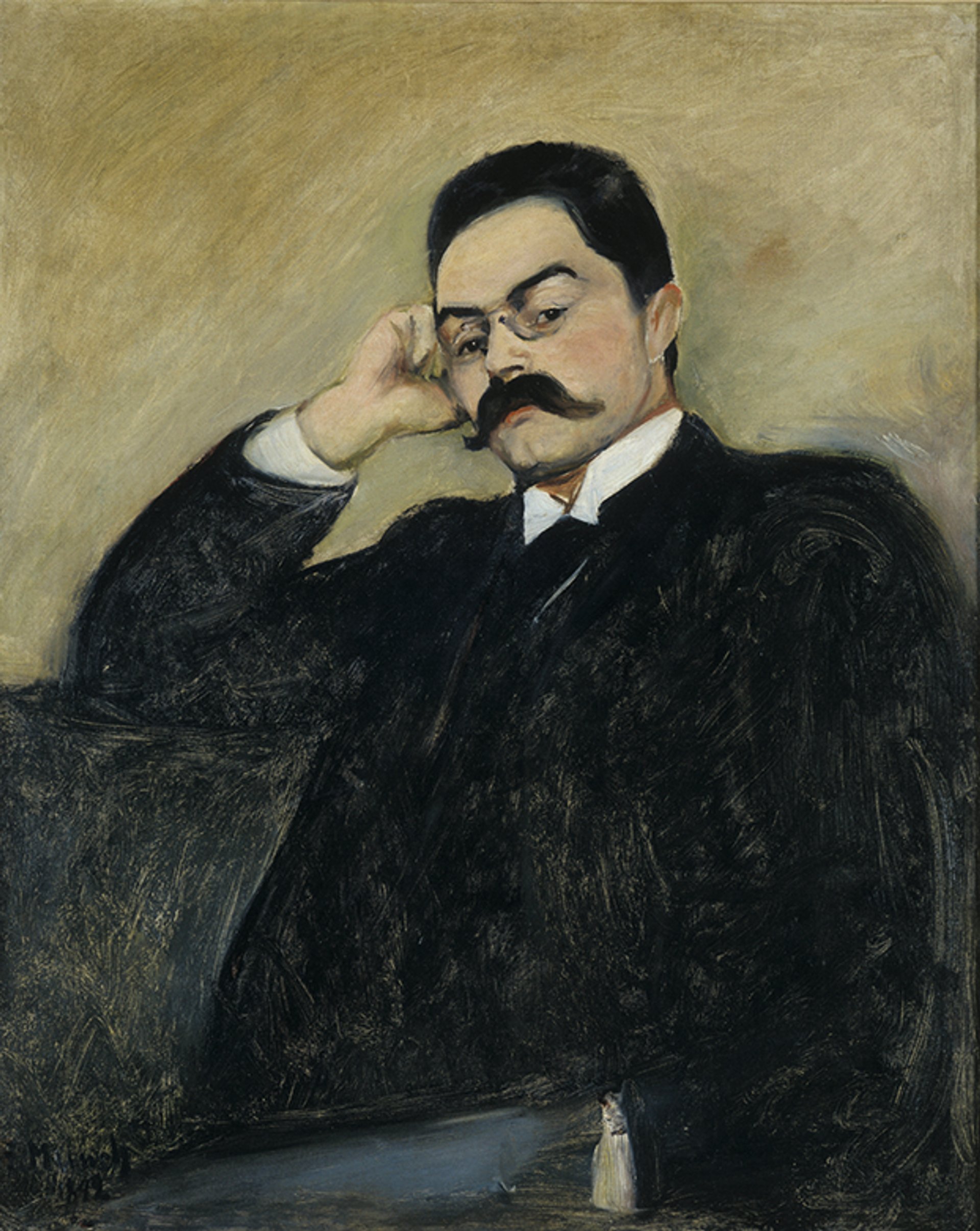

A key exhibition theme will be Munch’s ability to, in his own words, see “behind everyone’s mask”. The rakish, condescending air he gives to his 1885 portrait of the artist Karl Jensen-Hjell, for example, provoked outrage at the time. His 1907 depiction of the powerful industrialist Walther Rathenau—a dramatic vertical canvas dominated by an imposing figure, cigar held confidently in one hand and his shoes gleaming—surprised even its subject. “An awful character, isn’t he?” Rathenau apparently said. “That’s what you get for having your portrait done by a great artist—you look more like yourself than you really are.”

By the early 20th century, Munch had become one of Europe’s most popular artists and a “canny businessman”, Smith says. But he was close to his paintings, often creating a second version he would photograph himself beside and experiment with. “I think there’s a fascination with the supernatural and the idea of everyone having a hidden self,” Smith says. “But I think it’s also to do with how he felt so strongly that the pictures were his children, so found it very difficult to part with them.”

Hidden hug: a tiny couple appear low down in Munch’s Thor Lütken (1892) painting Photo: Munchmuseet/Sidsel de Jong

Also in the show are a selection of self-portraits, used by Munch to explore the depths of his own character. Another highlight is an 1892 picture of the lawyer Thor Lütken, which features a hidden landscape on the sleeve of the sitter showing two embracing figures.

From the bohemian Hans Jaeger to the psychiatrist Daniel Jacobson, those depicted in the show are people who not only financed Munch but also inspired, helped and provided him with friendship. Smith thinks the exhibition celebrates them as much as the artist himself.

The show ultimately seeks to position Munch as a man who was not in fact alone at all but connected—all the way through to his older years. “He was someone who was part of this wonderful European network,” Smith says. “He was a cosmopolitan.”

• Edvard Munch Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, 13 March-15 June