The Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, Spain’s museum of 20th-century art, has expanded its collection with 470 new works in a demonstration of its commitment to gender balance and racial diversity. More than half of the acquisitions are by women and a significant proportion by artists from under-represented ethnic backgrounds. Many are by promising young artists whose works are yet to enter art history books.

Around 100 of the works were bought by the museum over the course of last year, with Spain’s culture ministry providing almost 140 pieces, and nearly 160 donated by galleries, artists and collectors. The Reina Sofía Museum Foundation, which aims to promote cultural partnerships and public participation in the museum’s work, provided a further 80 works, most of them donations. The acquisitions amount to a total investment of almost €8m.

The new intake comes ahead of the planned inauguration of an updated permanent display in March 2026 illustrating the history of art from the late 1970s to the present day. “We are preparing new narratives,” Manuel Segade, the museum’s director, tells The Art Newspaper. “This requires new art histories to be told in different ways, so it was the perfect moment to include a lot of younger artists and less common figures.”

Of the new works, 56% are by women artists, up from the 37% of works acquired in 2022. This, Segade says, will help bring the collection in line with the spirit of Spain’s 2007 gender equality law, which requires public authorities to promote women in culture, and states that at least 40% of electoral candidates must be female. The director estimated that less than 20% of works in the collection were by women, adding that he hoped the proportion would be closer to 40% in ten years’ time. The acquisitions include Ángeles Santos’s La marquesa de Alquibla (1928).

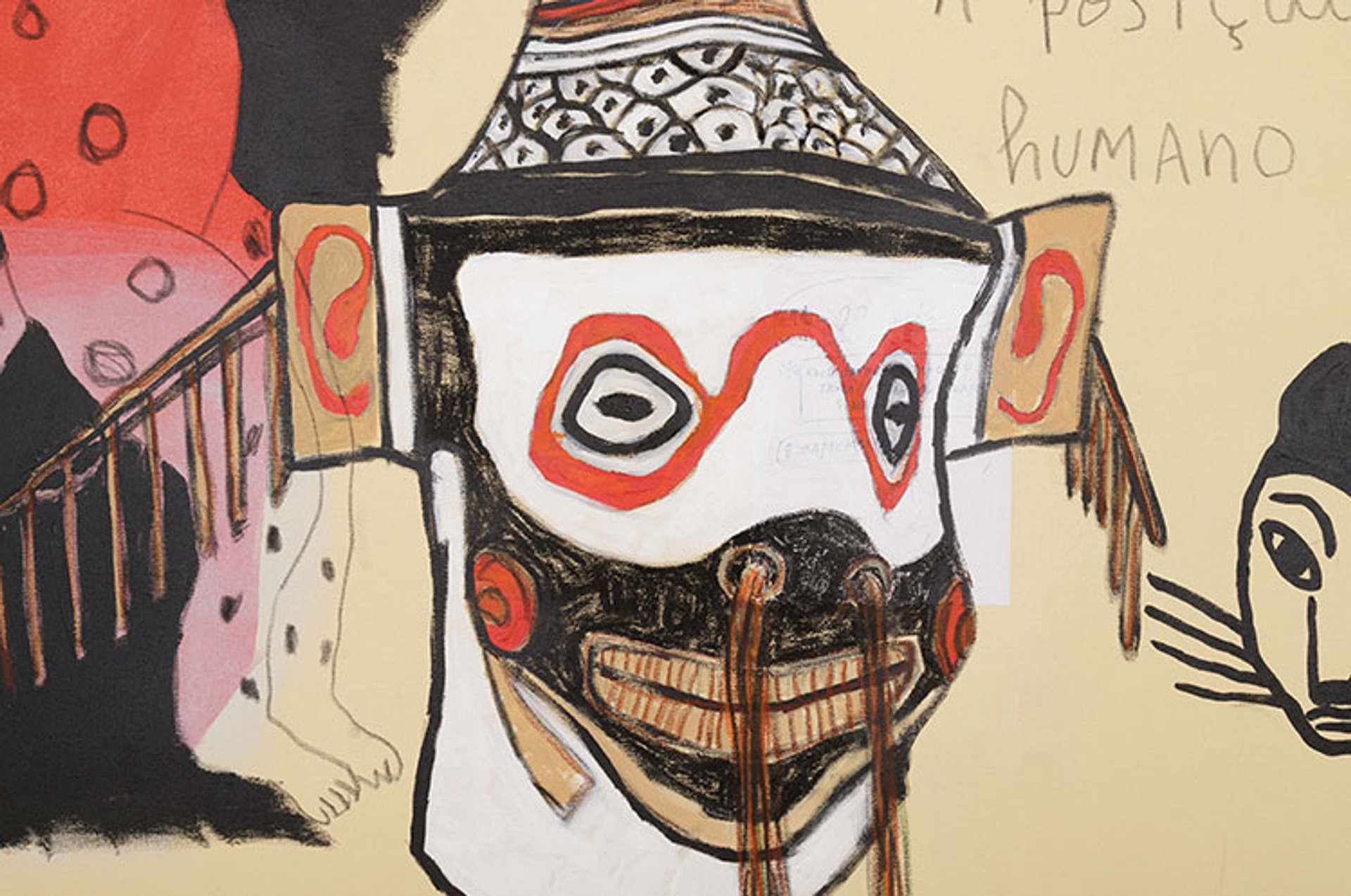

In an average year, the Reina Sofía Museum enriches its 25,000-strong collection, of which only 6% to 8% is usually on display, with roughly 300 works, Segade explains. Of those acquired last year, further focuses include Spain’s 1970s so-called Transition period—with new sculptures by Sergi Aguilar, inflatables by Josep Ponsatí and Pop art by Carme Aguadé entering the collection—as well as contemporary Spanish artists like Joan Morey and Rubén Grilo. The new works also include pieces by the Afro-descendant Spanish artist Rubén H. Bermúdez, the Colombian artist Miguel Ángel Rojas and the collage Mitológicas 2 (2023) by the Amazonian Indigenous artist Denilson Baniwa.

Former director attacked by right wing media

In 2023 Segade’s predecessor as museum director, Manuel Borja-Villel, ended his tenure after the right-leaning newspaper ABC claimed his curation amounted to a culture of “political propaganda” and accused him of trying to extend his tenure in violation of the museum's own rules. The museum claims the attacks were unfair.

Mitológicas 2 (2023) by the Indigenous Amazonian artist Denilson Baniwa is among the new acquisitions

© the artist

Segade says the selection of new works should not be seen as “woke or feminist” but about ensuring the collection better represents the evolution of contemporary art. “It’s not because of the interests of the museum but because of the nature of contemporary art itself,” he says of the acquisitions. “Contemporary art is impossible to understand without the presence of gender issues or racialised communities.”

Securing private donations, many of them from Latin American collectors, has promoted dialogue and “opened up the collection in new directions”, Segade says. He adds that the museum had “taken a gamble” on up-and-coming artists. “The youngest artists are the biggest bet because we are acquiring works by people who may not become big names,” Segade says. “A piece that is not so important in 20 years’ time remains important as a snapshot of the moment.” The director adds: “If artists are allowed to fail, institutions should be allowed to fail too”.

Following outcry from members of the Jewish community and Israeli embassy in Spain in May last year, the museum announced it had changed the name of “From the River to the Sea”, a series of lectures, conversations and meetings with artists that the museum had described as “pro-Palestinian”. “It’s not a problem to change a title if you are aware, you are achieving the opposite of what you hoped to achieve, that is, dialogue,” Segade says. “The important thing is to correct your errors.”