Since 2017, Cure³ has brought together prominent contemporary artists to raise money for Cure Parkinson’s, a UK charity dedicated to supporting research into a cure for Parkinson’s disease. Spearheaded by Susie Allen, Laura Culpan and Serena Starr of the international practice Artwise Curators, the project’s fifth edition promises to be the largest so far with more than a hundred artists participating in a special exhibition at Bonhams auction house in London from 1 to 5 February.

The return of a digital section to Cure³ is evidence of an increasingly hybrid art world. Of the 96 artists who supported the previous edition in 2023, seven digital artists raised £240,000 of the nearly £700,000 total. Cure³ is guest curated this year by Alex Estorick and Foteini Valeonti of reGEN, a curatorial initiative to raise money to fight degenerative diseases. It features 11 leading digital artists selling works through the generative art platform fx(hash), including five offering a physical counterpart. Notable among the roster are the pioneering net artists and indie game designers Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn, whose Generato non creato (2025) is a series of interactive digital sculptures that explores the relationship between digital and spiritual experience.

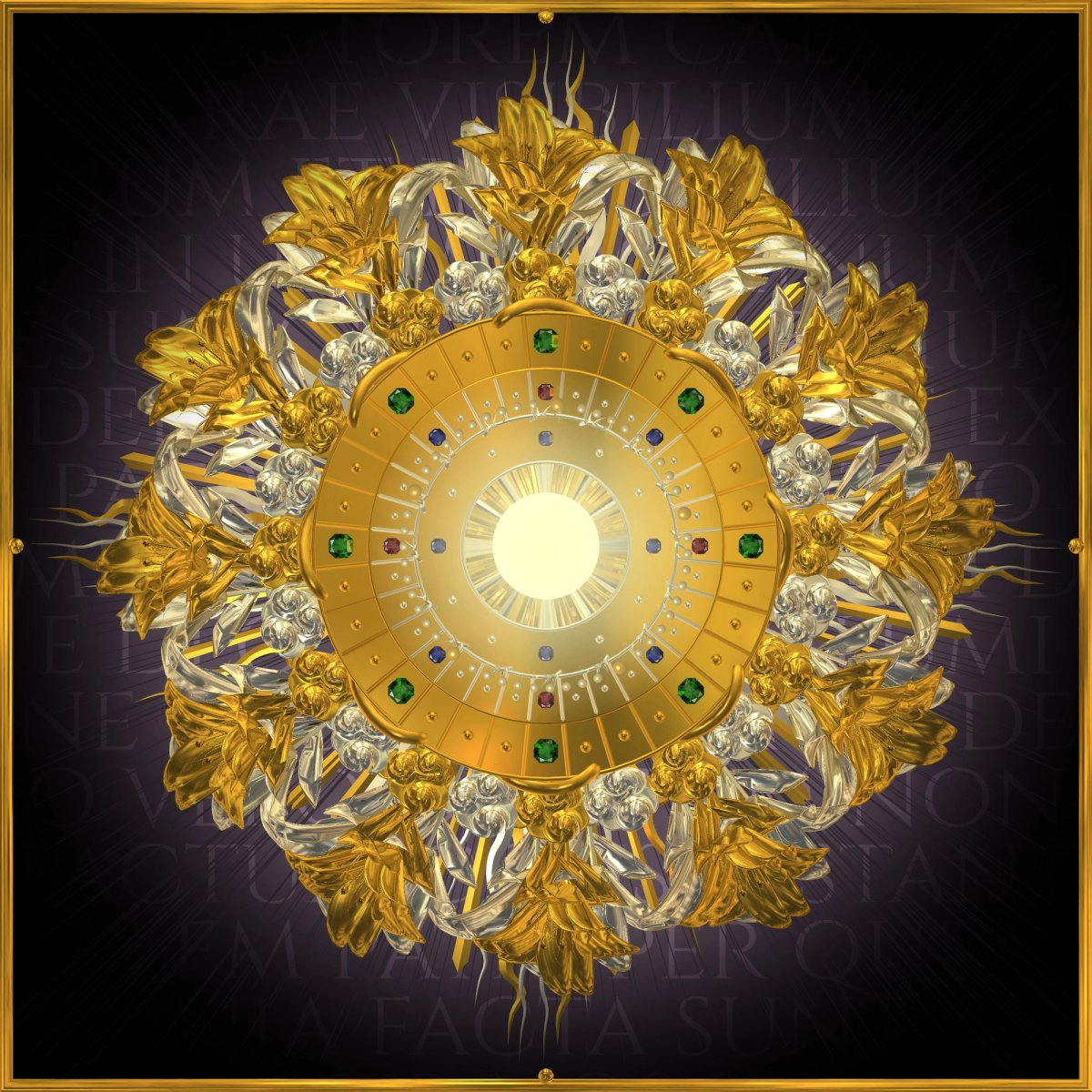

Auriea Harvey and Michaël Samyn Courtesy of the artists

Alex Estorick: How have you found the process of developing this new work of generative art using code?

Michaël Samyn: We’ve always made generative art. With our net art and video games, there have always been generative elements in our work. I’ve had a lifelong interest in decorative art as well as real-time art, simulation and interaction.

Auriea Harvey: My collaborative projects with Michaël have always involved one of us doing the thing the other can’t do, and we tend to like each other’s contributions. Cure³ was a good opportunity to work in this genre because it’s definitely not something I would normally do on my own.

At the start of our relationship neither one of us wanted to programme. I was a frustrated coder and still am a terrible hacker—I will just take a script and abuse it until it does something. Michaël is able to think about it with a view toward the end product. We found a game engine with a visual programming paradigm called Quest 3D, which was for architectural simulation, and talked to the people who made the tool. They told us not to make games with it, and we said: “Oh yes, we’re making games.” Our first was a multiplayer game. Thinking in terms of the effects you want to have on the person who is actually experiencing the work leads to a whole other way of thinking about code.

MS: Previously, a lot of our works had been very illusionistic, but when we made the transition from the web to video games, it felt more natural. One of the beautiful things about generative art is that you can start with a very simple object, a 3D object, replicate it a few hundred times and get a very complex thing. We’ve done that before, for example with our game Luxuria Superbia (2013). With our VR piece, Cricoterie (2018), when you put two characters together they make a third—you get all of these duplicating couples that have a certain life; it just keeps going and going until the computer can’t handle it anymore. We like to play with limits. If a net art piece crashed our browser, that was a good thing.

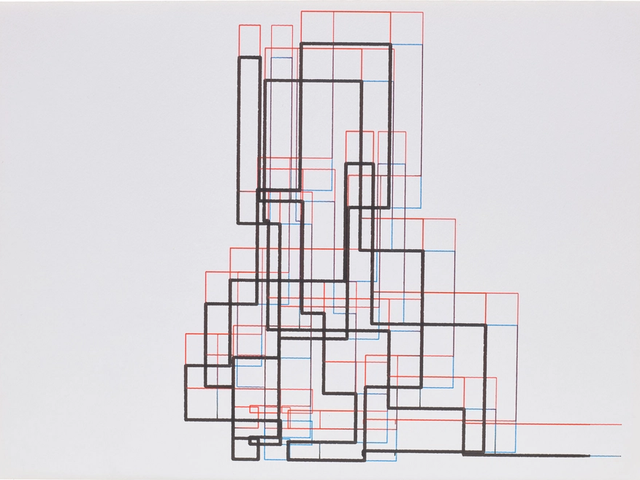

Marcelo Soria-Rodríguez’s above/beneath all & all above/beneath (2025) Courtesy of the artist

AE: Your project for Cure³ is designed to produce more than 100 variations. How have you found the process of testing and tweaking the system to produce a range of outputs that you’re happy with?

AH: An interesting aspect of generative art is that each outcome is different every time you reload it. But, to us, the distinction between what is generative and what is purely interactive is very arbitrary. At a certain point, this piece had a very different look and feel, with greater contrast. We were trying to get to a more harmonious whole and then Michaël changed something and all of a sudden it looked much more concrete and stark. He found the right balance in the numbers to make it look right.

MS: Our work for Cure³ is a flat image, but it uses an orthographic camera so we took the opportunity to put all the elements of the work into a cube in keeping with the theme of the exhibition. Viewers can manipulate the object in space because it’s also interactive. We want to let people touch them and play with them.

AH: 3D has been my core for such a long time that I’m happy we were able to integrate it into the Cure³ work in an elegant way.

AE: Did the fact that Cure Parkinson’s is dedicated to curing a degenerative disease influence your approach to this generative project?

MS: I have a strong childhood memory of a colleague of my father’s who suffered from Parkinson’s. I remember that he had two states: one in which he was shaking and the other when he appeared to be paralysed. Our title, Generato non creato, refers to the way Jesus is considered in the Nicene Creed as a son generated from the father, not created in the way an artist might make something. As technology evolves, our own works actually degenerate and start breaking. Sometimes we have to remake an entire game or project to make it work again.

AH: We had thought that our project Eden.Garden (2001), originally commissioned by SFMoMA, was irreparable. Now a new exhibition at ZKM [in Karlsruhe] called Choose Your Filter! is bringing the piece back. Eden.Garden was one of the proto-religious works that we made at the end of our net art career. At the time, we felt that the internet was a paradise that we wanted to present as a browser within the browser. In that project, you got a little prompt to type in the URL and the HTML code would create a garden for you to walk around. There were all these different elements, including animals, that you could see in real time. Michaël and I would dance as characters in the garden. At the time, people were saying that you couldn’t do a real-time 3D world on the web, but we made it happen in 2001. Then the whole thing died and it was like, “OK, paradise is truly lost on the web.” So to see it back again in emulation is very interesting. Many works in my recent survey show at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York were shown in emulation.

AE: You live in Rome, near Vatican City. This work looks like a digital ritual object that is both ornamental and sculptural. It feels very Roman.

AH: As Catholics in Rome, we go to all these beautiful churches to attend Eucharistic Adoration, where a monstrance is placed on top of the altar. Our piece is important to us because one of the saints of the Catholic Church, Pope John Paul II, had Parkinson’s disease and so we felt that this was also an interesting way of connecting to our faith. We were attempting to create a virtual monstrance inspired by those in the cathedrals of Rome. We’re hoping that the form it takes, through its light and the manipulation of its appearance, brings light in some way to other people.

• Alex Estorick is a co-curator of Cure³

• Cure³, Bonhams, London, 1-5 February. Digital sales at cure3.xyz