Mel Bochner, the American artist who played an essential role in the development of conceptual art in the 1960s and applied an irreverent sense of humour to his work across many media over the ensuing half-century, died on 12 February. His death was announced by the New York- and Paris-based gallery Peter Freeman Inc. He was 84.

Bochner was born in Pittsburgh, where he attended Carnegie Institute of Technology, earning his BFA in 1962 before moving to New York City. There he became involved in the city’s artistic avant-garde just as its attentions began shifting from Abstract Expressionism and Pop art toward Minimalism and conceptual art. Bochner became indelibly associated with the latter genre of art and organised what has been considered the first conceptual art exhibition, Working Drawings And Other Visible Things On Paper Not Necessarily Meant To Be Viewed As Art, at the School of Visual Arts (SVA) in 1966.

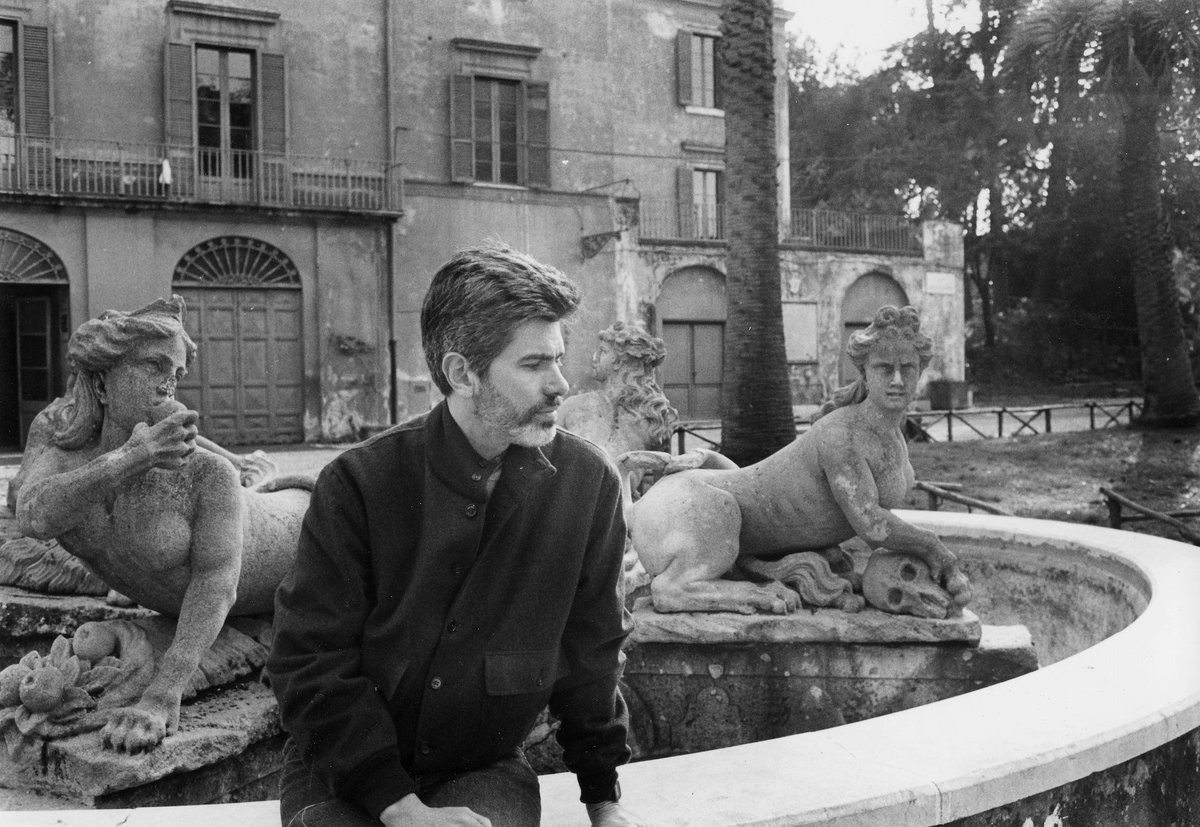

Mel Bochner at Galerie Heiner Friedrich, Münich, in 1969 Courtesy of Bochner Studio and Peter Freeman Inc, New York/Paris

“Starting around the summer of [19]66, this group kind of coalesced, which was Sol [LeWitt], Eva [Hesse], [Robert] Smithson and Dan Graham and myself,” Bochner said in an oral history interview with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art (AAA) in 1994. “And we saw each other, you know, one or the other of us was seeing another everyday, we were getting together, we were going to the movies, we were visiting each other's studios, we were talking, we were going out for dinner, so there was a very intense exchange of ideas.”

Around this time, in addition to teaching at SVA, Bochner began writing about art, publishing reviews and articles in Arts Magazine and Artforum. His earliest article for the latter, about serialisation in Modern and contemporary art, set out a preliminary taxonomy and cannon of what would come to be known as conceptual art.

“The serial attitude is a concern with how order of a specific type is manifest,” he wrote. “Types of order are forms of thoughts. They can be studied apart from whatever physical form they may assume.”

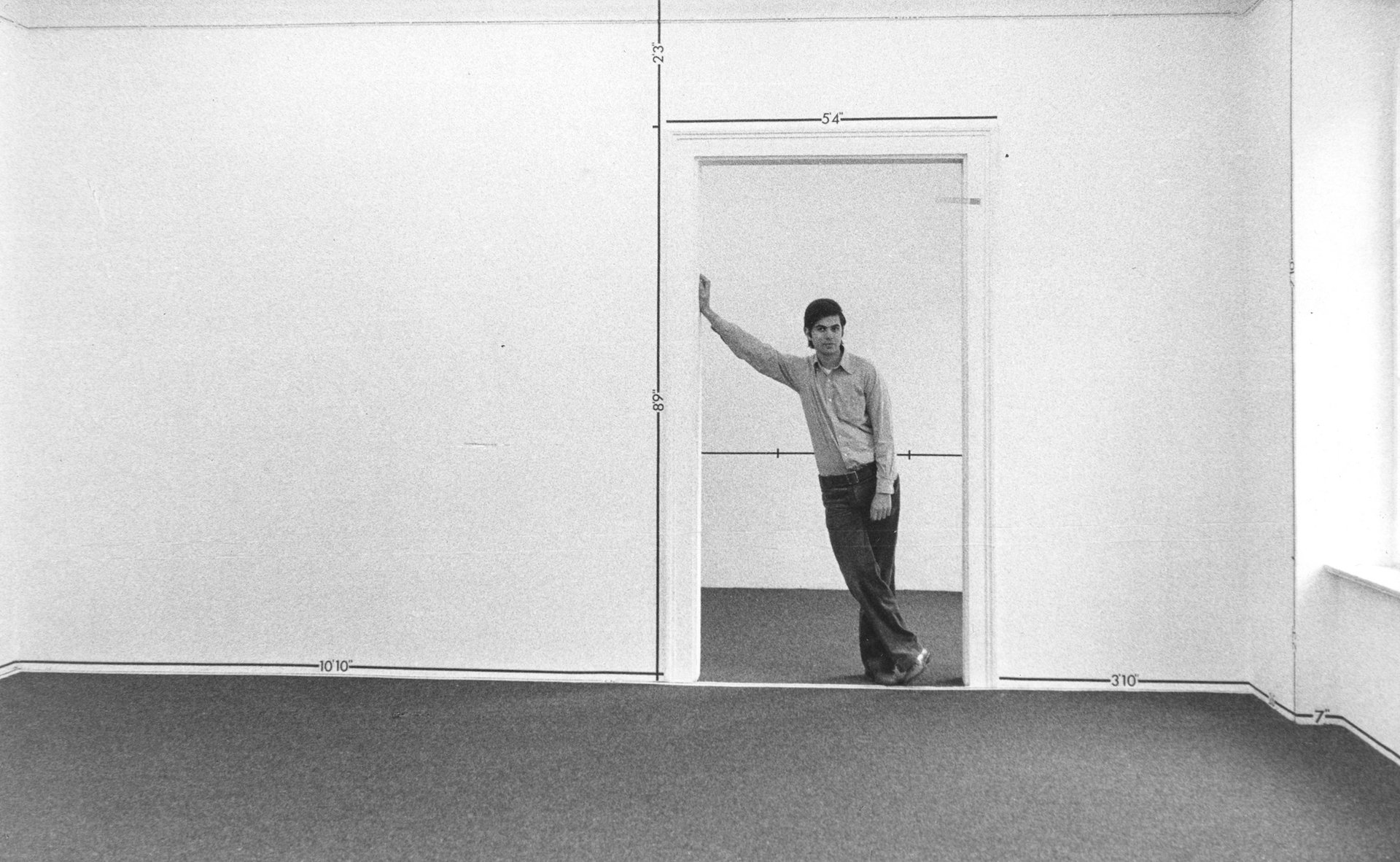

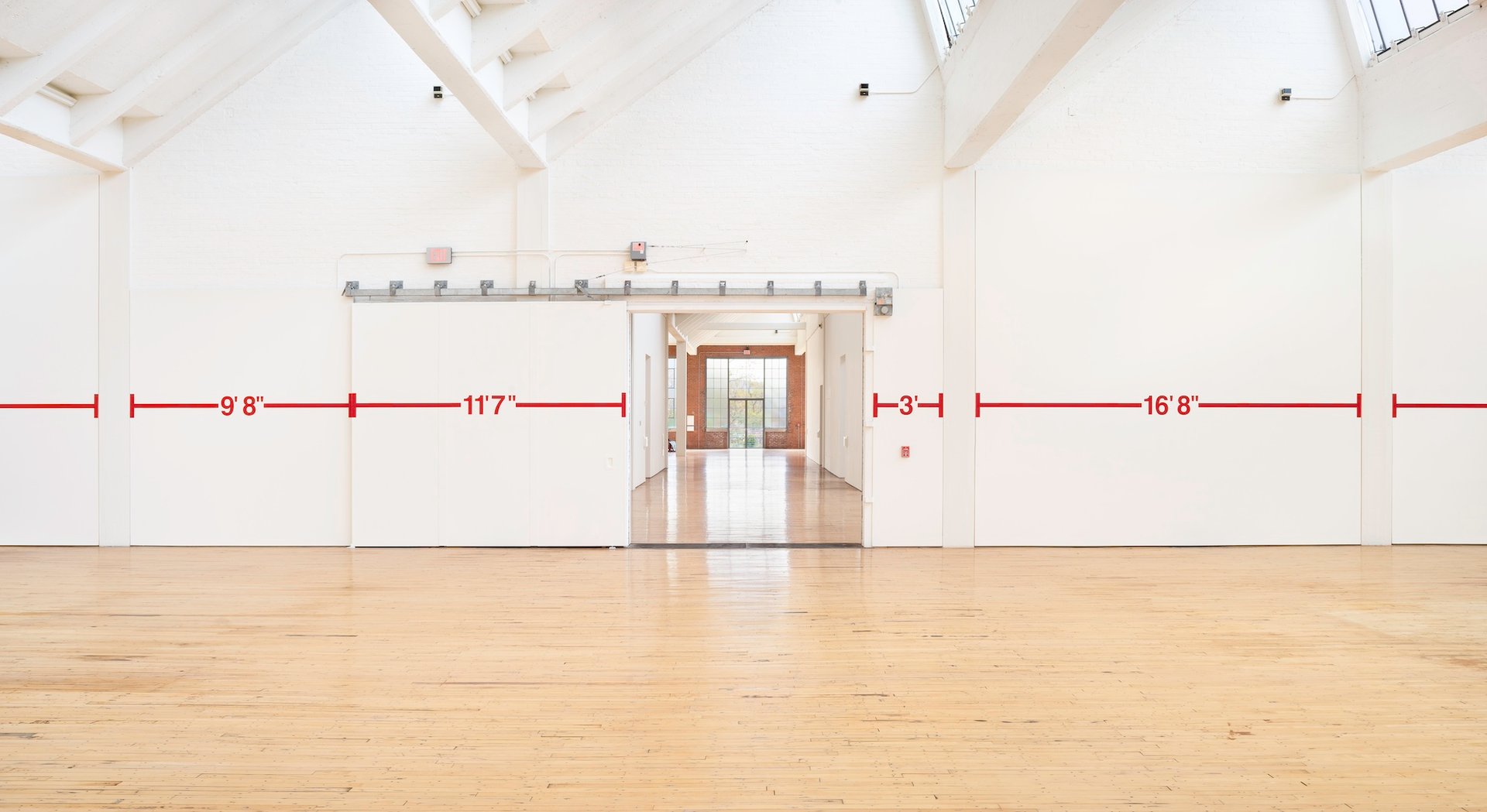

Mel Bochner, Measurement Room: No Vantage Point, 1969/2019. Installation view, Dia:Beacon, Beacon, New York © Mel Bochner. Photo: Bill Jacobson Studio, New York, courtesy Dia Art Foundation, New York

His own work attested to the originality, adaptability and intellectual rigour of art rooted in seriality, rules and information systems. His 1966 work 36 Photographs and 12 Diagrams consists of a grid of the titular 48 objects, depicting grids of numbers and photos of wooden cubes arranged in corresponding configurations. Another early breakthrough was his Measurement Room (1969), which debuted at Heiner Friedrich Gallery in Münich. He used black tape to delineate the various wall sections of the gallery’s architecture, marking the length of each section with numbers applied to the walls. The piece, which effectively turned the gallery into a kind of architectural schema of itself, was repeated several times in different venues over the ensuing decades. In 2019 the Dia Art Foundation commissioned Bochner to create the largest version of the piece at its building in Beacon, New York.

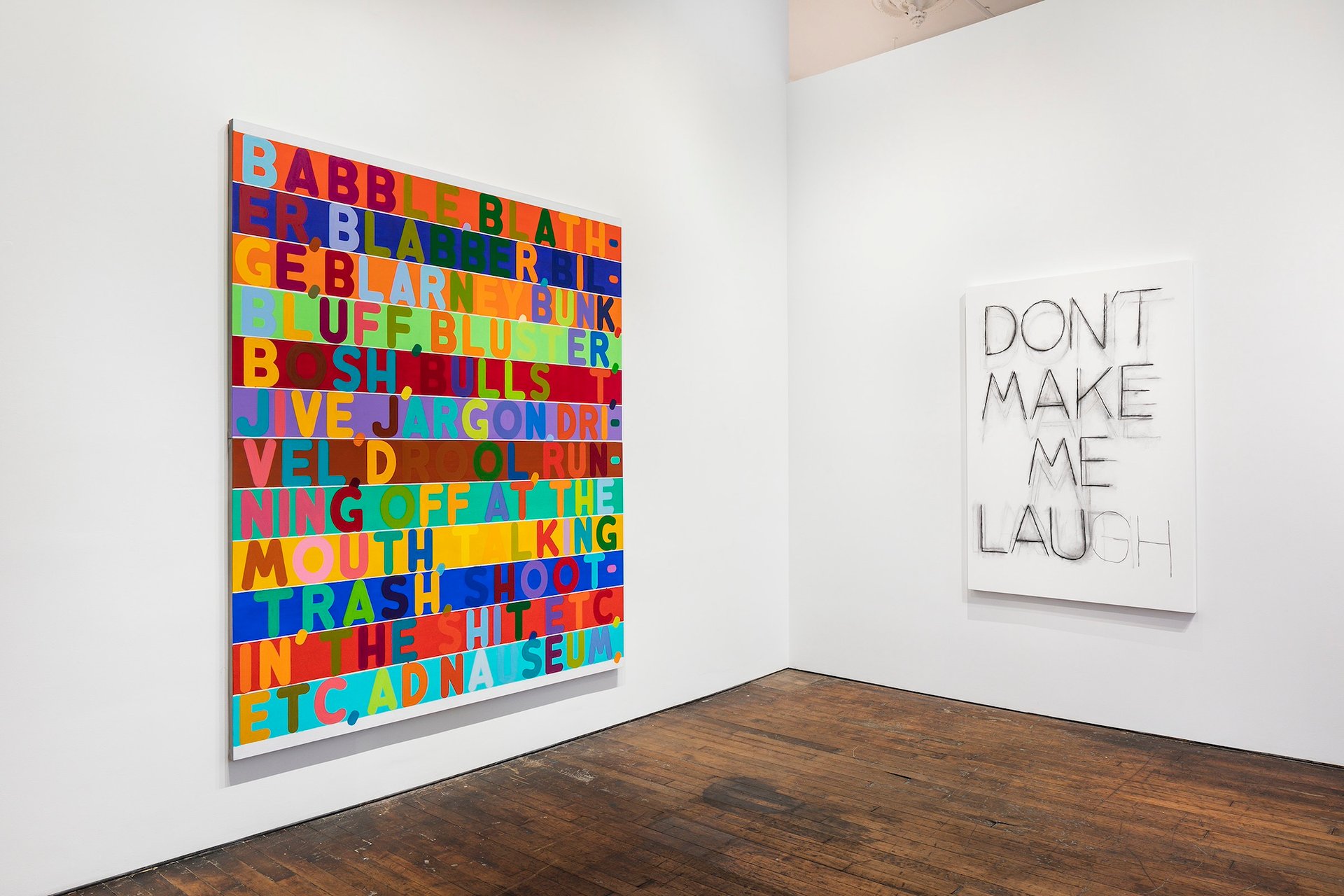

In ensuing decades, Bochner became best known for text-based works—spanning paintings, prints, drawings, installations and more—in which he decontextualised or repeated certain words and phrases until they became detached from any stable meaning. Frequently recurring words and phrases included “blah”, “obliterate” and “ass backwards”, or thematically linked series of text like exclamations or insults.

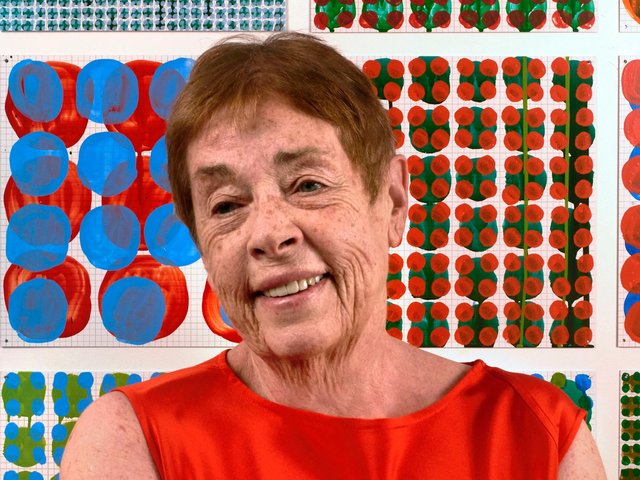

Installation view of Mel Bochner: Seldom or Never Seen 2004-2022 at Peter Freeman Inc in 2022-23 Courtesy Peter Freeman Inc, New York/Paris

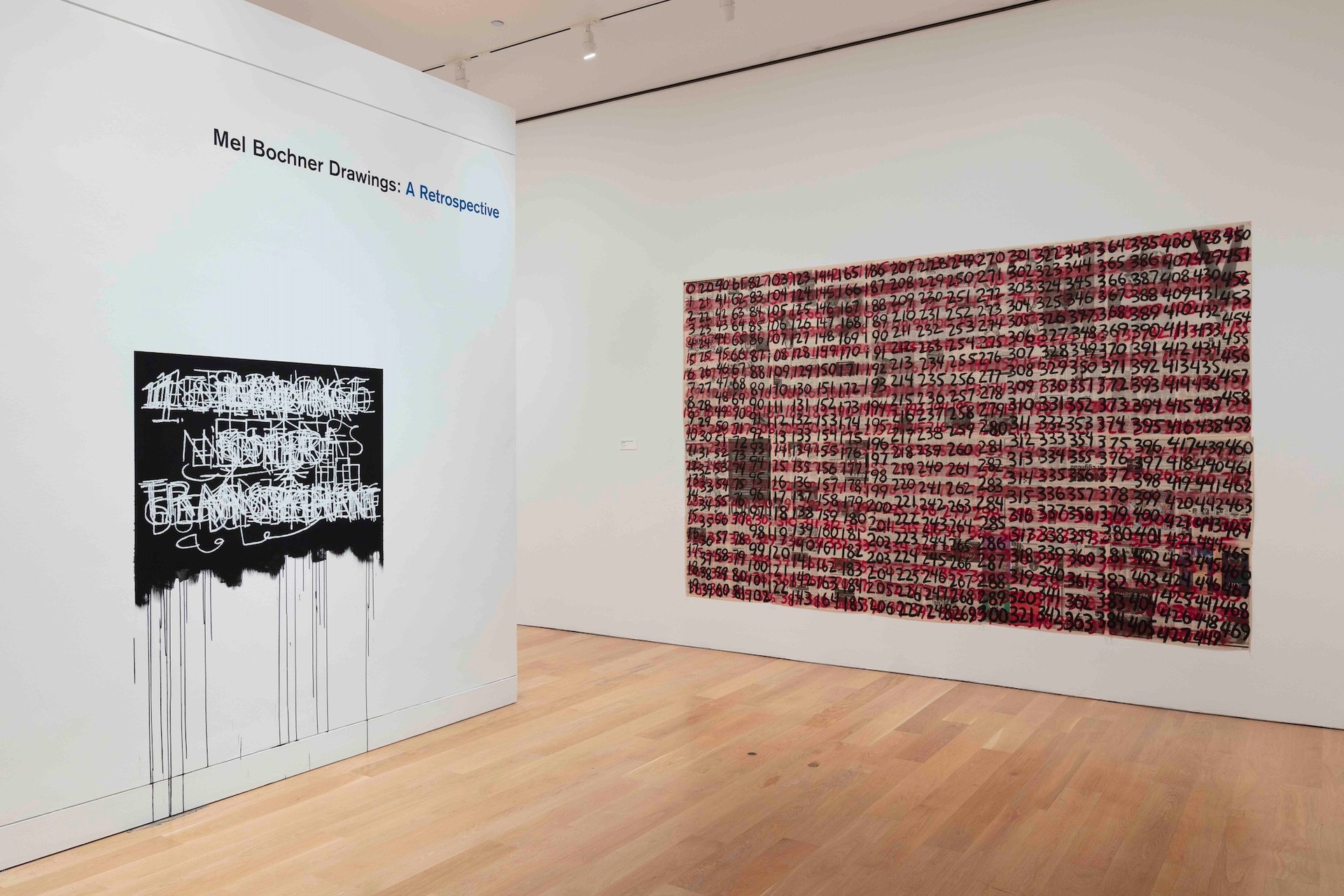

“In 1970, I wrote on a gallery wall, ‘Language Is Not Transparent.’ It was a statement that all language has hidden agendas and motives. The first thing that power corrupts is language,” Bochner said in a 2022 interview on the occasion of a retrospective of his drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago. “My work doesn’t address political issues directly. In works like Exasperations, I want the meaning to dawn on the viewer, not bludgeon them. But, at the same time, I do agree with Charlie Chaplin: ‘If it isn’t funny, it isn’t art.’”

“Mel was the perfect mensch, always generous, even when correcting a misunderstanding,” says Peter Freeman, whose eponymous gallery was one of a half-dozen representing Bochner’s work and closed its tenth solo show of Bochner's work last month, said in a statement. “On the one hand, he was a leading figure in the development of conceptual art in New York in the 1960s and 70s, a major artist who helped change the course of how we understand art can be made. On the other, he was the unpretentious eyewitness whose stories would bring you into the studios and minds of mentors like Barnett Newman or colleagues like Eva Hesse and Robert Smithson. For almost 50 years Mel was a great friend to me like no other, from whom you could never learn enough, with whom you could never laugh enough.”

Installation view of Mel Bochner Drawings: A Retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago Courtesy the Art Institute of Chicago

In addition to the recent institutional shows at Dia Beacon and the Art Institution of Chicago, Bochner was the subject of important solo exhibitions at the Jewish Museum in New York in 2014; the Whitechapel Gallery in London, Haus der Kunst in Münich and the Fundação de Serralves in Porto in 2012-13; Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh in 1985; and the Yale University Art Gallery in 1995. He also taught at Yale University for decades, beginning in 1979.

In the 1994 oral history interview with the AAA, Bochner recalled the origins of his approach to conceptual art as a desire “to demonstrate the idea the way you would demonstrate a theorem in geometry by making a little drawing and working it out. I wasn’t clear about what I wanted to do, but I was clear that I didn’t want to do Minimalism. I wasn't interested in the object nature of art. I was interested in the philosophical nature of art.”