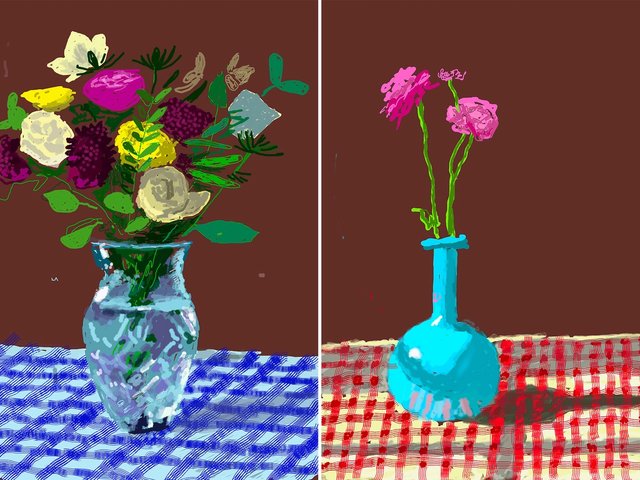

When most people think of David Hockney, famous works such as The Splash (1966), Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972) or even the digital paintings he created during the Covid-19 pandemic will likely come to mind. But several years before the artist was producing even the oldest of these pieces, he was working in a rather less recognisable style.

In The Mood For Love: Hockney in London, 1960-1963, which opens at Hazlitt Holland Hibbert, London on 21 May, presents works made during and immediately after Hockney’s time at London’s Royal College of Art (RCA), when he was experimenting with different aesthetics.

Louis Kasmin, the curator of the exhibition, describes the show’s two main themes: “There’s the Love paintings, which have a kind of graffiti—they’re quite phallic and in your face, and they've got words like ‘shame’ or ‘queer’ scrawled across them. They’re really energetic,” he explains. “And then we move into a more kind of figurative approach, where Hockney starts to present the key people in his life.”

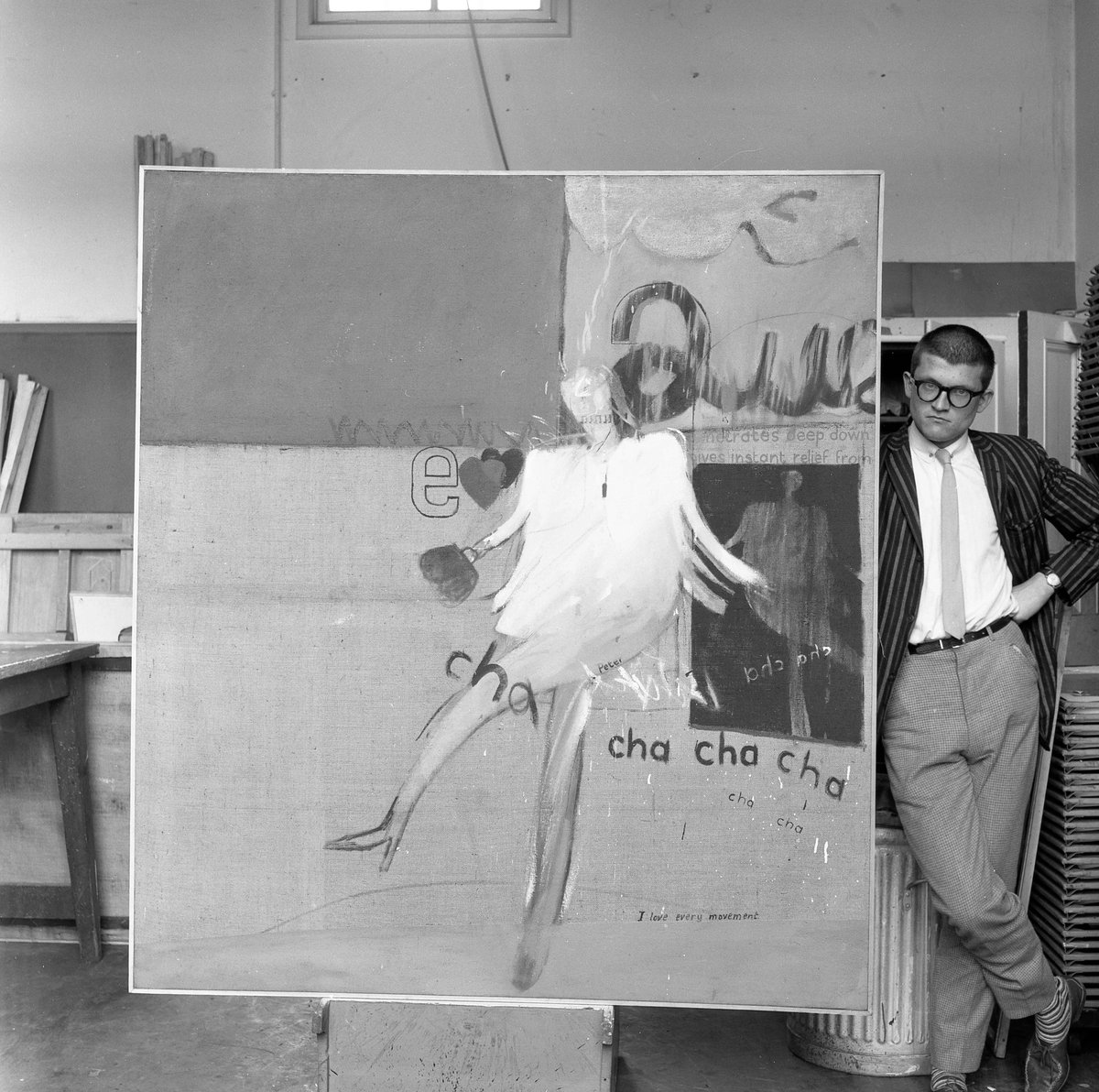

David Hockney, I'm in the Mood for Love (1961) Royal College of Art, London

The show, he says, aims to shed light on elements of the artist’s development that are often overlooked. “These are works that people rarely see—and certainly not in this context,” explains Kasmin, a sales associate at Hazlitt Holland Hibbert. “We want to highlight just how unbelievably raw and full of extraordinary energy the works are. How, even when David was still at the RCA, he'd become this figurehead, he’d already got a kind of aura around him.”

A range of expertise and cross-generational work has gone into putting the show together. Kasmin’s grandfather, the gallerist John Kasmin, represented Hockney from 1961 until the early 1990s, and sold several of the exhibition’s works into private collections during the 1960s, where many have remained ever since. John’s meticulous records of these transactions allowed his grandson to make cold calls and send hopeful emails, eventually tracking down some of the show’s least exhibited works.

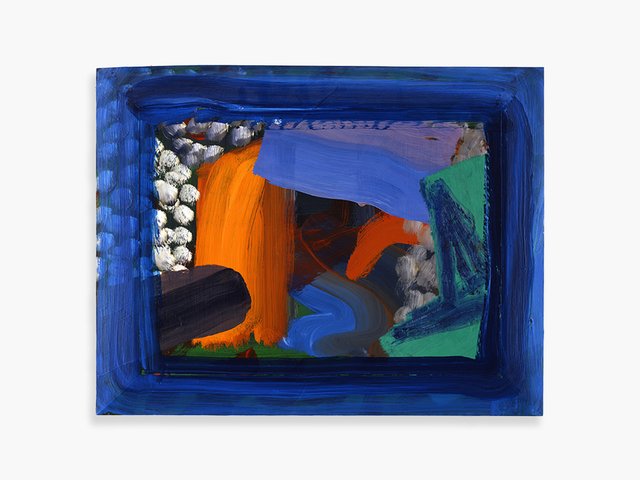

David Hockney, Two Friends (in a Cul-de-sac) (1963) © David Hockney

The art historian Marco Livingstone—who contributed to the show— meanwhile, has a close knowledge of Hockney's early work and helped Kasmin investigate the provenance of one key painting, Composition (Thrust). The abstract work, in the collection of the RCA, was previously dated 1962, however Livingstone raised doubts about this.

“We were looking at this painting, and we felt it was part of the Love series, which is all from 1960,” Kasmin explains “By 1962 Hockney has already moved into a more figurative and legible way of painting, far less abstracted.”

David Hockney, Composition (Thrust) (1960) © Royal College of Art. Royal College of Art, London

A conversation with the David Hockney Foundation proved the exhibition’s team right, and the date of the painting was adjusted to 1960. “An amazingly small detail, but it was also still quite thrilling,” Kasmin says.

Composition (Thrust) appears to show Hockney exploring themes seen throughout his work in this period: his own sexuality—seven years before homosexuality was partially legalised in England—and different forms of affection.

In this work the artist’s brush strokes are physical, accompanied by the frank words “thrust” and “Queen”. This contrasts with The Cha Cha that was Danced in the Early Hours of 24th March 1961, painted just a year later, where the artist’s approach is much softer. The figure in the later painting, who Kasmin describes as a man for whom Hockney had romantic feelings at the time, is accompanied by the words “I love every movement”.

“What love meant to David at that point—there are so many meanings,” Kasmin reflects. “I think maybe he was exploring the physicality of love and of sex, while also presenting more intimate versions of it.”

Kasmin acknowledges that it is impossible—or at least unwise—to attempt to attach definitive interpretations to these early, abstract works, and does not expect future visitors to reach unanimous conclusions about them.

“We just hope that by showing people these quirky, oddly shaped, interesting paintings and drawings, that they will come away with a slightly altered vision of how he is as an artist,” he says. “This is David at his most unfiltered, most creative and imaginative.”