Given the contemporary biennial sprawl—hundreds of artists, even more artworks—curators understandably often opt for short titles. These are loose umbrella terms for a deluge of art-making: casually evocative, rarely foundational.

Read the full 18-line titular poem for Sharjah Biennial 16, which opened on 6 February, though, and something altogether more compelling—more urgent—takes hold. Each line starts with "To carry", then lists something you might variously hoist on to your back, or bear in your bones (a home, a history, a trade, a wound, language, land, equatorial heat). Some of these burdens are arresting for their specificity: "a library of redacted documents", "Te Pō [the beginnings]". Others are entire poems: "to carry the embrace of a river current"; "to carry the rays of a morning without fear". Together, they set the scene for a show that wants to grab you by your insides. And, largely speaking, it does.

Installation view of Lorna Simpson, From Earth & Sky (2016–2018)

Photo: Motaz Mawid

First off, this 16th edition of the region's longest-running biennial is an actual deluge: five curators, 17 vastly different venues, almost 200 artists representing as many different backgrounds, more than 200 new commissions, more than 650 works in total — and an exhibition area that comes close to outlining the full 2,590 sq. km of the emirate's territory, from coast to coast by way of the desert and the Hajar mountains. Seeing everything, let alone really taking it all in, is a tall order.

When Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, the director of the biennial and the overarching Sharjah Art Foundation, convened her curatorial quintet (Alia Swastika, Amal Khalaf, Megan Tamati-Quennell, Natasha Ginwala and Zeynep Öz), she says many in her entourage were not convinced. "How's that going to work?", they asked. "Whatever happens, happens," she replied. "Just trust me." The result is a return to the experimental edge that the last edition, instigated by the late Nigerian visionary Okwui Enwezor in 2023, was criticised for having lost.

That comes with risks. The biennial's brick of a guide book refers to a "wild polyphony" and there are moments when this leads to actual cacophony. Sound bleeds between installations; authorship is occasionally blurred; at other times, it is hard to tell where a work ends and the raw, adaptive-reuse space (an abandoned house, a decommissioned market stall) within which it is exhibited begins. But those chaotic edges nonetheless feel fertile, as does the absolute wealth of written, sonic, woven, printed and visual information.

Megan Cope, Kinyingarra Poles (2024) © the writer

Big-name artists (Lorna Simpson, Wael Shawky, Luke Willis Thompson) are outnumbered by campaigners (the UK-based Voice of Domestic Workers group), scholars (the Samoan architect and ethnographer Albert L Refiti), community projects (the Thai feminist organisation Womanifesto), archives (the Singing Well archive of indigenous East African music; the Indonesian Concrete Thread Repertoire) and other groups (the Aotearoa New Zealand-based Te Matahiapo Collective).

Several artists' works are activated not by performance but ritual: the ancient Chinese divination charts John Clang draws for individuals and organisations (while sat at a table behind a large canvas on which he's drawn the biennial's own chart); Refiti's Moana dialogues (visitors gather in a circle with him and say both their names and whom they've brought with them, spiritually); the emotionally charged chanting procession that was held around the Quandamooka artist Megan Cope's installation, Kinyingarra Guwinyanba, within the Buhais Geological Park desert setting. Cope introduced that work—a sea-garden of wooden poles from which hang bunches of oyster shells)—by "paying respect to the ancestors here", a sentiment which echoes throughout the wider exhibition.

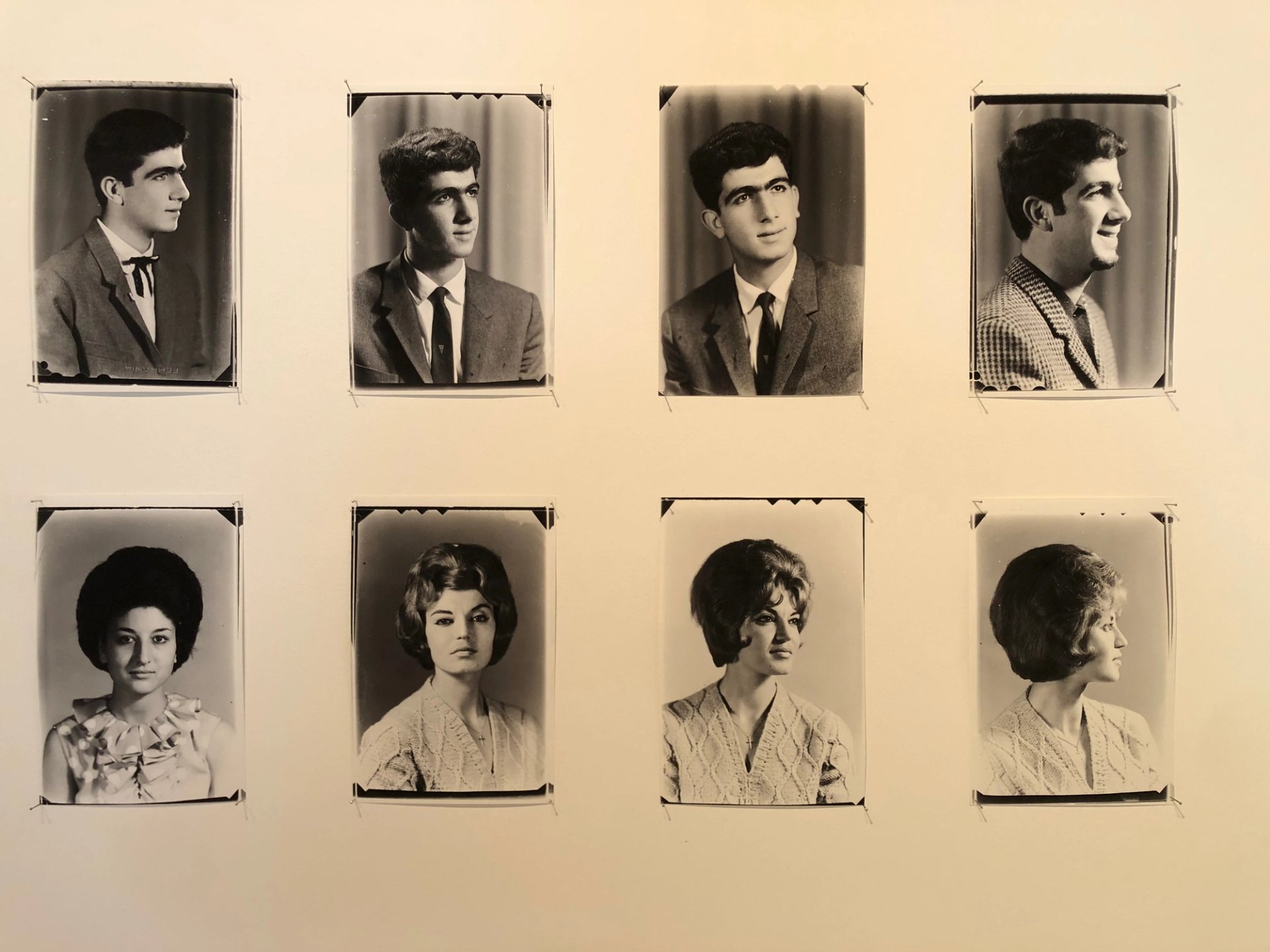

Detail of Photo Kegham of Gaza: Unboxing (2020-2024) by Kegham Djeghalian Jr and his father Kegham Djeghalian Sr © the writer

There is not much photography on show but what is included of the medium is excellent, in particular the Photo Kegham archive of work by the Armenian-Gazan photographer Kegham Djeghalian. There is a bit more painting, with special mention to Kenyan artist Kaloki Nyamai's huge bold canvases hung unframed in a geometrically painted space. At several points, an older generation of artists such as the Kenyan sculptor Morris Foit and the late Bahraini painter Nasser-Al Yousif provide these exciting windows into the many overlapping art histories, and art worlds, in play. Elsewhere, there are exhibitions inside exhibitions, a whole set of published books, live events and, crucially, a lot of sound, done very well.

First, in the central Sharjah City spaces, Michael Parekōwhai's installation, He Kōrero Pūrākau mo te Awanui o Te Motu: Story of a New Zealand river, features an eye-catching red baby grand, entirely carved in Maori fashion, and played, gloriously, by world-class musicians. In the desert, Zeynep Öz's Farm Project in the oasis town of Al Dhaid, is a collection of six audio pieces installed in the holes and rubble of an abandoned date plantation. These include a field of metal poles doubling up as speakers by the German veteran composers Hauptmeier Recker; the Lebanese musician Sary Moussa's bassy decay; the Turkish composer Başak Günak's countertenor lament; and a dreamy windborne composition hidden in some trees by Berke Can Özcan, a fellow Turk now based in Abu Dhabi.

Kaloki Nyamai, Kwata, 2024 © the writer

Nearby, the Guatemalan artist Hellen Ascoli's masterful loom-based sculptural installation spreads out through the rooms and courtyard of a crumbling house, narrow weavings motorised to slowly loop through intricately assembled wooden partitions. Similarly, the Puerto Rican artist Jorge González Santos has invested one of the old residencies in the Heart of Sharjah with a beautifully subtle collection of indigenous Taino craft in the making (candles being dipped, lace being woven, incense burning) around a fire burning in a sandy inner courtyard. It is profoundly domestic and congruent within its location: both a paean to and a dirge for ancient ways of living.

With "to carry songs" as one of the titular directives, the lament is a distinct leitmotif. The Pakistani multidisciplinary artist Risham Syed sings a Guru Nanak poem with her classically trained mother and her daughter in the soundtrack for several wheat fields she has planted. These will change colour as they grow throughout the five months of the show.

Installation view of part of Jorge González Santos’s Jatibonicu (People of Sacred High Waters) (2024-25) © the writer

The American artist Suzanne Lacy, meanwhile, in her 2017 two-screen film, The Circle and the Square, marries the Sacred Harp-style congregational singing of Appalachia (where you sit in a square and belt out polyphonic hymns, beating the air with your palm to keep time) with a group of imams gently singing in the round, eyes closed in prayer. It is unbelievably moving.

Several other film works demand your attention. Arthur Jafa is present with a trippy song in pixellated charcoal that you sink into—happily—for what feels like forever. The Bangladeshi filmmaker Naeem Mohaiemen directs a feature-length love story in an abandoned hospital. And the Kuwaiti-Puerto-Rican artist Alia Farid's altogether shorter but equally mesmerising film, Chibayish, delves into the delicate ecosystem in which children of a water-buffalo herding community play in the reeds on the southern Iraqi coastline. “She looks scary”, a boy laughs, as a little girls holds up a torch to her face, ghostlike in the dark. The dual sense of both resilient creativity and imminent loss of something invaluable is electric.

Still from Suzanne Lacy, The Circle and the Square (2015–18) Photo: courtesy of Suzanne Lacy Studio, the Whitworth Art Gallery and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Some of the artists invited by the First-Nations curator Tamati-Quennell live off the grid, entirely outside the mainstream art world. They felt compelled to take part, she says, because of the cross-cultural solidarities and decolonial perspectives that have long been nurtured in the emirate. Al Qasimi's father, Sheikh Sultan bin Muhammad Al-Qasimi, the ruler of Sharjah, grew up under British occupation, and was, according to his daughter, "an activist". An historian and playwright too, Al Qasimi has long invested in his kingdom's educational and cultural institutions, founding, among other things, this biennial. Longterm foreign residents point to this as a principle difference with the other emirates, notably Dubai.

In her introductory press conference, Hoor Al Qasimi duly related her wider team's outlook back to that of "our fathers, our mothers, our grandparents" then couched this specific edition firmly in the present. "Before I end my speech," she said, "I would like to ask everyone to keep in mind the people of Palestine, Lebanon, Sudan, the Congo, Armenia and all other parts of the world where people are less fortunate than ourselves."

Since taking the reigns of the biennial from her father in 2003, Al Qasimi has sought to turn it into a tool for fostering what many term "South-South" connections: dialogue, between communities of the global non-Western majority, that decentres those historic mainstream art world hubs (New York, Paris, London).

Her recent positioning at number one on the ArtReview Power 100 list underscores how effective that vision has been. European observers note the near complete absence of European and North American voices in this edition. They also highlight how regional competitors, notably Saudi Arabia, are seeking to emulate Sharjah's cultural successes. Arab-language observers, meanwhile, emphasise the biennial's value as an educational instrument for critical thinking and counter-narratives at a time of increasingly fraught geopolitics, with one Lebanese journalist describing it as a "brave event".

Al Qasimi's open-ended nod to “all other parts of the world where people are less fortunate than ourselves” is, of course, doing a lot of heavy lifting. Amid the constant references to participants' backgrounds, there will inevitably be omissions (I saw no inclusion, for example, of Uyghur perspectives). Similarly, amid the keen positioning of the biennial within the global geopolitical context, the way Jewish communities the world over have been affected by rising antisemitism since 7 October feels unacknowledged.

Installation view of Raafat Majzoub, Streetschool Prototype 1.1, Everything—in your love—becomes easy (2019/2024) Photo: Motaz Mawid

Further, anyone whose artistic practice—even survival—depends on a critical unpacking of gender or sexuality is likely to leave the biennial feeling unseen. Lastly, when the magnetic Lebanese architect and filmmaker Raafat Majzoub has expletives censored out of his filmed dialogue, you question, too, what space is afforded those artists for whom the mess of the world can only be processed or expressed, not through care, but through the abject.

These counterpoints notwithstanding, Sharjah Biennial 16 is a polyphonous, multitudinous "come sit over here" (and here and here and here): each work not about any given beloved place but comprehensively of and for it. As such, this event is not marginal or niche: it is the future.