The artist and writer Walter Robinson—known for creating bright and dryly humourous paintings, and for writing incisive and sometimes irreverent musings on the New York art world—has died, aged 74. The artist’s wife, the painting conservator Lisa Rosen, told Artnet News that Robinson died from liver cancer. He is survived by Rosen, his daughter and two grandchildren.

In a statement to The Art Newspaper, a representative of the gallery Sébastien Bertrand in Geneva, which has represented Robinson since 2016 and has held four solo exhibitions of his work, says Robinson was a “cherished artist whose bold vision and distinct voice have left an indelible mark on contemporary art”.

“In times when ego and self-celebration prevail, his modesty and willingness to push others forward will never be forgotten,” the representative adds. “Walter was a brilliant multi-faceted artist. In his artistic practice, he translated the visual language of consumerism and desire into works that were as thought-provoking as they were visually captivating. His ability to elevate the everyday and explore the boundaries between high and low culture made his work timeless and resonant.”

Walter Robinson, Nightmare, 2021. Courtesy Mamco, Geneva. Courtesy Sébastien Bertrand, Geneva

Robinson was born in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1950, and raised in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He came to New York in 1968 to study psychology and art history at Columbia University and lived and worked in the city for the rest of his life. In 1972, he enrolled in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Independent Study Program as an art critic. Around the same time, he began editing the art journal Art-Rite, a periodical published between 1973 and 1978 that featured anonymous writings on the New York City art scene.

Alongside artists and writers like Sol LeWitt and Lucy Lippard, Robinson co-founded the non-profit Printed Matter in 1976, an organisation that presents artists’ books as standalone works of art. The seminal non-profit was one of the first to focus on publishing and distributing artists’ books, and celebrated for allowing artists to take over their own production. It became a non-profit in 1978 and moved to its present storefront in Chelsea in 2019.

Around the time of Printed Matter’s launch, Robinson became part of Collaborative Projects, a collective whose members included artists like Kiki Smith, Jenny Holzer and others. They banded together to produce their own exhibitions and raise their own funds, taking a community-minded approach to art projects.

Walter Robinson, Self Portrait, 1984 Courtesy Sébastien Bertrand, Geneva

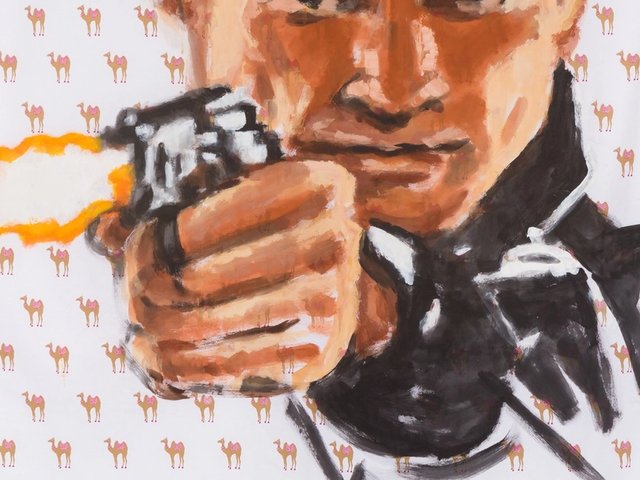

As an artist, in the 1970s Robinson began producing emotionally-charged paintings in the style of pulp fiction detective novel covers from the 1940s and 50s. He was a member of the Pictures Generation, creating work that aimed to reject “the avant-garde, posing and phoniness”, he said in an interview with the Whitney Museum in 2017.

Robinson said his work aimed to embrace themes related to “evolution, biology and desire, which underlies everything in the end”. He sometimes painted on bedsheets, a practice he attributed to being influenced by the German artist Sigmar Polke, who often painted on fabrics. Women, couples embracing and everyday objects like beer bottles and cheeseburgers are some common motifs in his work.

Walter Robinson, Anonymous Cheeseburger, 2018 Private collection, courtesy Sébastien Bertrand, Geneva

Robinson’s work is held in several museum collections, including the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, and the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art in New York—the latter of which holds a music video he co-directed for the influential punk band Suicide, called Frankie Teardrop (1978).

As a writer and editor, Robinson worked for East Village Eye in the 1980s and was a news editor for Art in America between 1980 and 1996. He became the founding editor of Artnet Magazine in 1995, one of the first online art publications, which helped launch the careers of several well-known art writers and critics like Jerry Saltz, who told the New York Observer that Robinson had “one of the most munificent, open-minded, sharp-eyed takes on the art world”.

From 1993 to 2000, Robinson, Paul Hasegawa-Overacker and Cathy Lebowitz ran GalleryBeat TV, a gonzo-style public access show where the trio offered commentary on contemporary art happenings around the city (and were often ejected from the spaces they were shooting). The show, once called “idiotic” by Julian Schnabel, ran for 130 episodes and featured artists like Brice Marden, the Guerrilla Girls, Cindy Sherman and others.

Walter Robinson, Spy, 2025 Courtesy Sébastien Bertrand, Geneva

When Artnet Magazine closed in 2012, Robinson returned his attention to painting and had a late-career resurgence. He had a retrospective in 2014 that travelled from the University Galleries of Illinois State University to other venues. In 2016, Robinson had a retrospective with Jeffrey Deitch in New York, and a solo exhibition at Vito Schnabel in St Moritz in 2017.

In 2013-14, Robinson was a columnist for Artspace. In his 2014 essay “Flipping and the Rise of Zombie Formalism”, he coined the term “Zombie Formalism”, a disparaging term to describe a particular type of abstract painting seemingly created specifically to cater to the art market’s tastes of the moment.

Although Robinson maintained a studio practice throughout his life, he did not consider himself an accomplished artist. In an aforementioned interview with the Observer, he said: “I didn’t become a successful artist because I didn’t want it enough. Sometimes it seems like you have to really want something to get it. Other times it seems like it’s handed to you on a silver platter.”