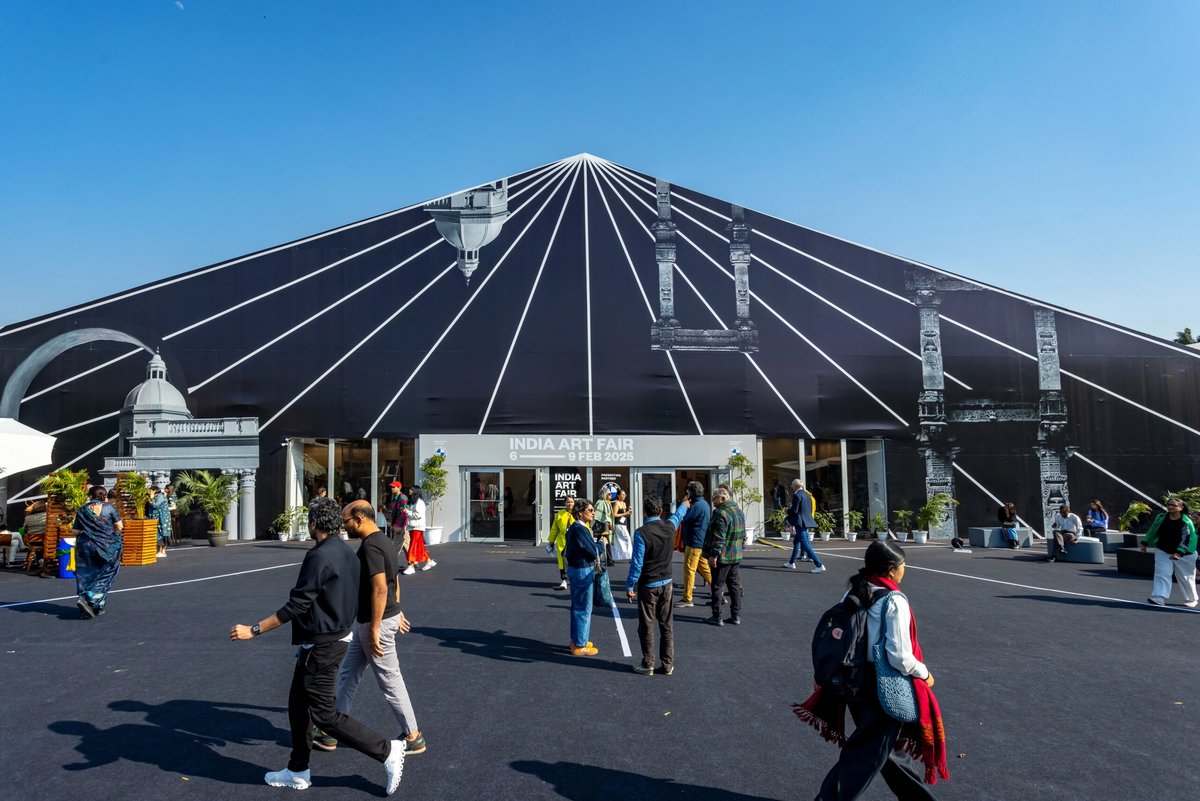

The India Art Fair (IAF, until 9 February) is holding its 16th edition during tense Delhi state legislative elections, the results of which will be announced tomorrow (8 February).

Many exit polls predict that the far-right Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) will unseat the centrist Aam Aadmi Party (AAP), which has governed the union territory of Delhi since 2015. This would be the first victory in Delhi in more than two decades for the Hindu nationalist BJP, which has helmed India’s national government for 11 years under prime minister Narendra Modi.

“As far as we can, we try not to censor the art on show,” says Jaya Asokan, IAF’s director. “We have always placed the artists first and respected their desire to say what they want about political and social matters, and we endeavour to show those works at the fair. But we are, of course, conscious that there are elections going on, and that we are in the seat of the national government.”

Inside the IAF tent, which can be found on the grounds of the National Small Industries Centre (NSIC), a government agency, the effect of the elections has been limited: exhibitors were required to set up a day early and extra security is present. But India’s wider swing towards right-wing religious fundamentalism is leaving its mark on the event, with organisers and exhibitors increasingly cautious about showing works that address hot-button issues. These include explicitly anti-BJP sentiments, and art about intercommunal violence, Hindu-Muslim relations and Pakistan. An international gallerist, who preferred to remain anonymous, says that they were advised by IAF to reconsider bringing a Pakistani artist to the fair. However, it is worth noting that nine Pakistan-based artists are still being shown at the fair, including Sameen Agha at Indigo + Madder and Arslan Farooqi at Anant Art Gallery.

Rising censorship

It is not just the elections that have made people more cautious. Last month, one of IAF’s exhibitors, DAG, was at the centre of a widely reported censorship scandal after a drawing of a naked Hindu deity by the artist M F Husain was seized from the gallery by the Delhi police under a court order. The move followed a complaint from a member of the public that the work “offended her religious sentiments”. The gallery managed to overturn the order, and denies any wrongdoing as alleged by the complainant "who has publicly claimed to be principally driven by a religious agenda”.

Ashish Anand, the owner of DAG, says that the Husain work is still in police custody, but he expects it to be returned soon. Not to be defeated, the gallery has brought another Husain painting of a mythological woman, albeit one who is not a deity, nor fully nude.

Reports of the DAG incident appear to have rattled some exhibitors. At the stand of Emami is a series of paintings by the Vadodara-based artist Ali Akbar PN, based explicitly around Islamic culture, and featuring mosques and men in abayas and topis (robes and prayer caps worn by Muslim men). The surfaces of the works are partially effaced; one depicts a large mosque beneath which stands a crowd of people, punctuated by flecks of red. A director at Emami declined to speak on record to The Art Newspaper about the context of the work.

Such caution is not exercised without reason. Many visitors will recall the 2020 incident in which Delhi police forcibly removed works about the mass anti-government protest movement, Shaheen Bagh, from the stand of the Italian Embassy Cultural Centre.

While many works at the fair are politically pointed, they achieve this in more subtle or elliptical ways. A standout of this year is Project 88, whose solo stand of new works by the artist Trupti Patel features a wall based series of 29 sculptures made of crude earth, representing the states of India. “The work is a critique of the disastrous government policies on agriculture,” Patel says.

Threshold in Delhi, meanwhile, is showing gouache on paper works by Anindita Bhattachyarya, which render the preamble to the Indian Constitution in Urdu, the lingua franca of Pakistan. Urdu, which is estimated to be spoken by around 50 million people in India, is “deeply rooted in India’s syncretic traditions”, but “has become a contested site—politicised, alienated from its shared heritage”, Bhattachyarya writes in a text about the work. The gallery has pointedly chosen not to include this text on site at the fair, its director says.

Another exhibiting gallerist notes that at the fair’s 2020 edition, when police removed the Shaheen Bagh works, their gallery showed a photograph of a man attending the same protests, which was not targeted because it was less explicitly contextualised.

Artists always find a way

Instances of artists navigating a tense political climate is also the subject of a solo exhibition by the artist Shilpa Gupta, which is taking place a 30-minute drive from the fair at Bikaner House, an art space owned by the Rajasthan state. Several works, including an installation of speakers emitting recordings of poetry by prisoners of conscience, speaks to the censorship faced by artists across the world. As Gupta tells The Art Newspaper, “artists always find a way to say what they need to say”.

This may include alterations to work shown in public settings. Last month in Mumbai, the artist Reena Kallat opened her show Cartographies of the Unseen (until 6 April) at the publicly funded Dr Bhau Daj Lad museum, exploring themes of the fragility of democracy and the impossibility of national borders. The show’s centrepiece in the museum’s hall is the textile installation Verso-Recto-Verso-Recto (2017) in which sheets of fabric are stitched with words from constitutions of nations that are politically partitioned or in conflict, such as North Korea and South Korea or Mexico and the US. Following a consultation with the museum, the constitutions of India and Pakistan are not being shown.

As the Delhi state election votes are counted, political commentators note that neither party has provided a coherent arts policy. “For the past decade, Delhi has been caught between the AAP controlling the city and the BJP controlling national government, meaning a lot of its culture has been sidelined and ignored,” says Yasmin Kidwai, a documentarian and former Delhi municipal councilor.

Anish Gawande, a spokesperson for the Indian Nationalist Congress Party, agrees that “culture remains an elusive topic” in the Delhi elections. He notes of the wider political climate that “increasingly over the past decade, artists and galleries have faced the difficult choice of either having their shows shut down or self-censoring their practice. Thankfully, however, we seem to have gotten better at navigating these circumstances. Young artists in particular are finding ways to subvert surveillance and censorship in innovative ways”.

Somewhat reassuringly, Kidwai adds that should the BJP win, the party's “narrow culture policy” is unlikely to be as effective in Delhi as it is in other parts of the country, due to the sheer plurality of the city. “Cultures here are inherently intermingled, you simply can’t divide them.”