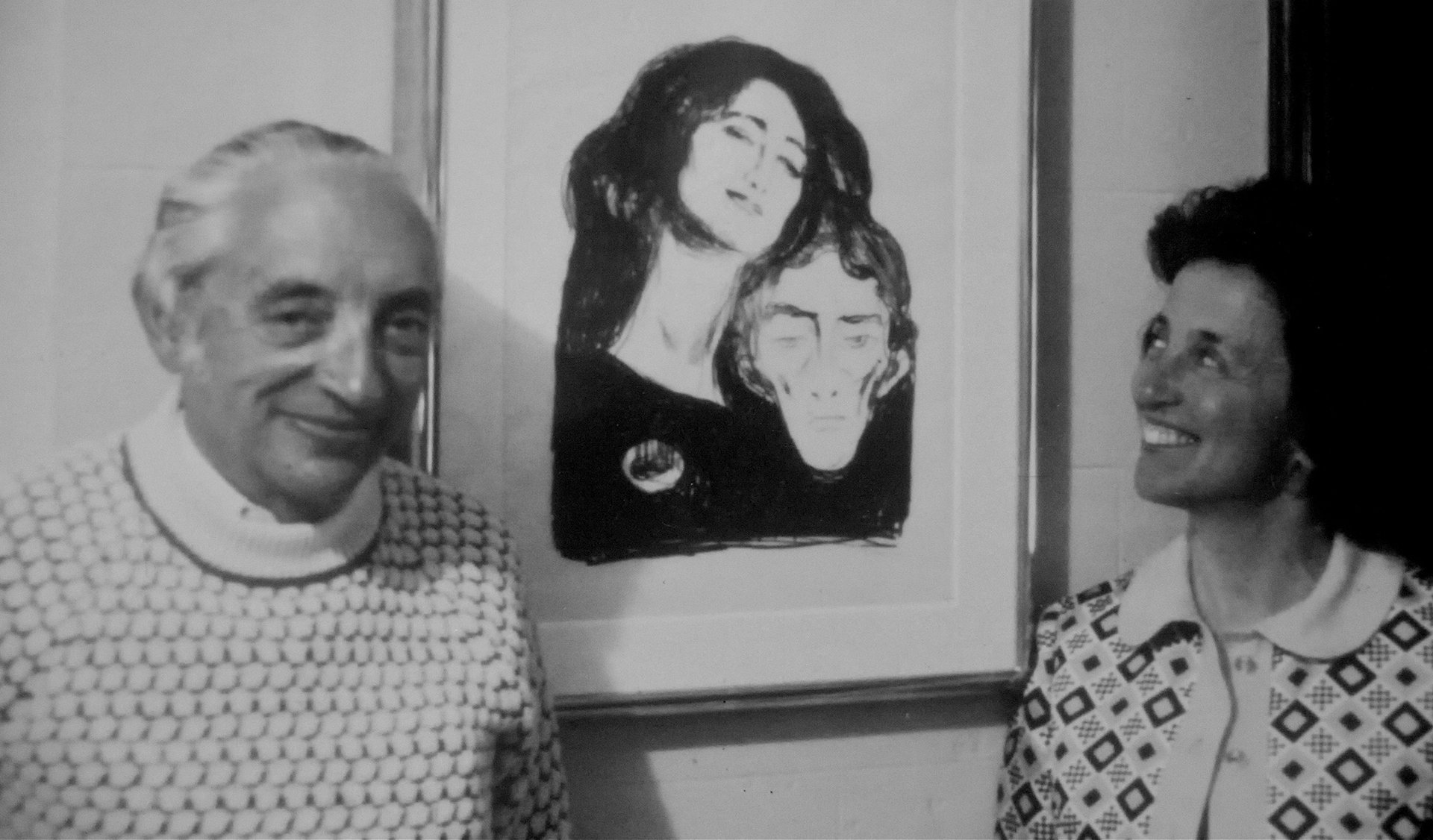

In 1969, the New York couple Philip and Lynn Straus celebrated their 20th wedding anniversary by acquiring Salome, a lithograph by Edvard Munch. The 1903 work, printed in black ink on yellowish Japanese paper, shows a couple merging into a single being, and it set the Strauses on a decades-long path. They went on to assemble one of America’s premier collections of the Norwegian artist, including a wide range of works on paper and several key paintings. Philip, an investment banker, died in 2004, and Lynn, a former teacher, died in 2023. This week, the Harvard Art Museums are announcing a gift of 64 Munch works owned by the couple.

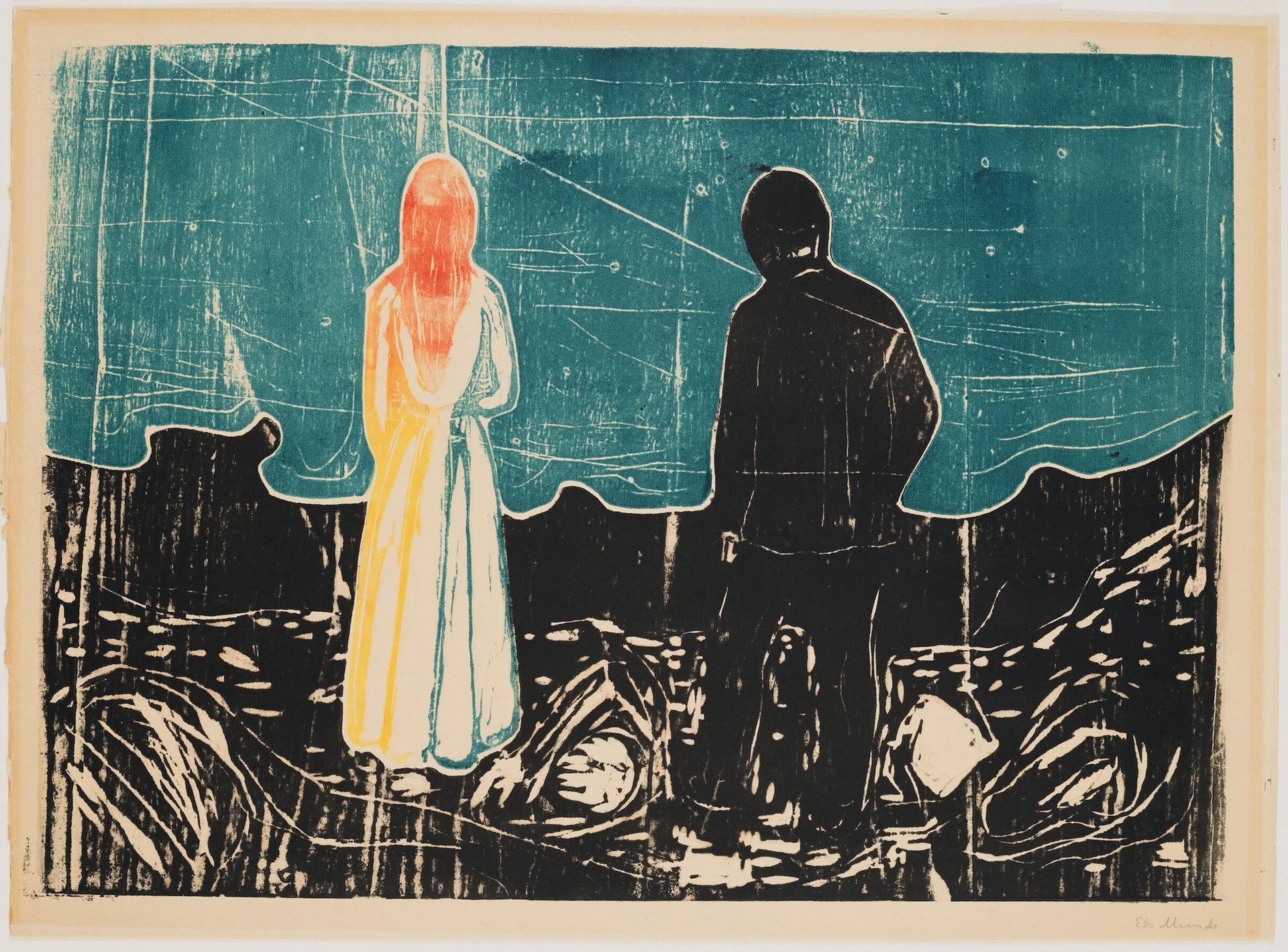

Along with the Salome print, standout works include six iterations of Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones)—an oil-on-canvas painting from 1906-08 and five works on paper of the same motif, all showing a man and a woman, separate from each other and staring out to sea. The prints cover a broad range in method and tone, from a mid-1890s etching to a mid-1910s heavily-coloured woodcut. Each of these five prints, though “formally similar”, is “a distinct work of art”, says Elizabeth Rudy, curator of prints at the Harvard Art Museums. Together with the oil version of the scene, she adds, the museums can now provide “a truly deep dive” into how Munch explored one of his more notable motifs.

Edvard Munch, Train Smoke, 1910. Oil on canvas. Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Philip Straus, a Harvard College alumnus, and his wife had a longstanding relationship with the museums. This latest bequest follows on earlier donations, including a $7.5m gift to Harvard’s fine arts training and research facility, the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. The 1906-08 painting, along with Train Smoke, a 1910 Munch painting that is also part of the new bequest, have just completed their own Straus Center conservation treatments. Until Lynn’s recent death, says her son Philip Straus, Jr, the two paintings were in the living room of the family home in Mamaroneck, New York.

Not only did the couple choose to live with these paintings, adds Straus, a 73-year-old photographer who lives in Philadelphia, their Munch prints “were mostly on the walls.

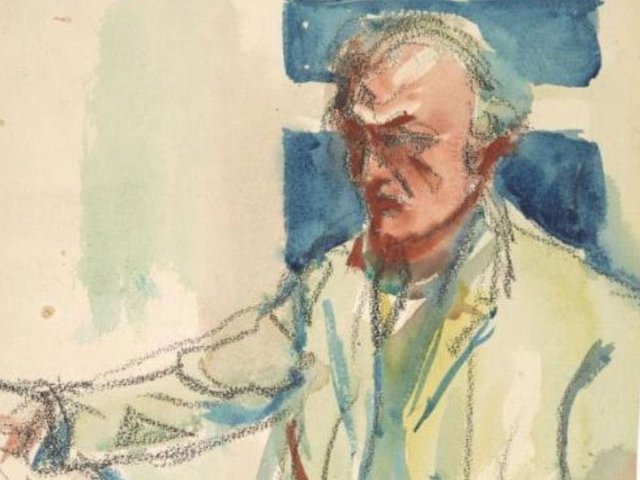

Philip and Lynn Straus with their first Edvard Munch print, Salome (1903), around 1969 Photo: Courtesy Philip A. Straus, Jr

Examination of the two oil paintings in the bequest have yielded surprising information, says Lynette Roth, curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum. (The Busch-Reisinger is one of the Harvard Art Museums’ three constituent institutions, which are all housed in the same Renzo Piano complex, opened in 2014.) Roth says the technical examination revealed that an area in the foreground of Train Smoke, now faded to almost white, was originally “a warmer red”.

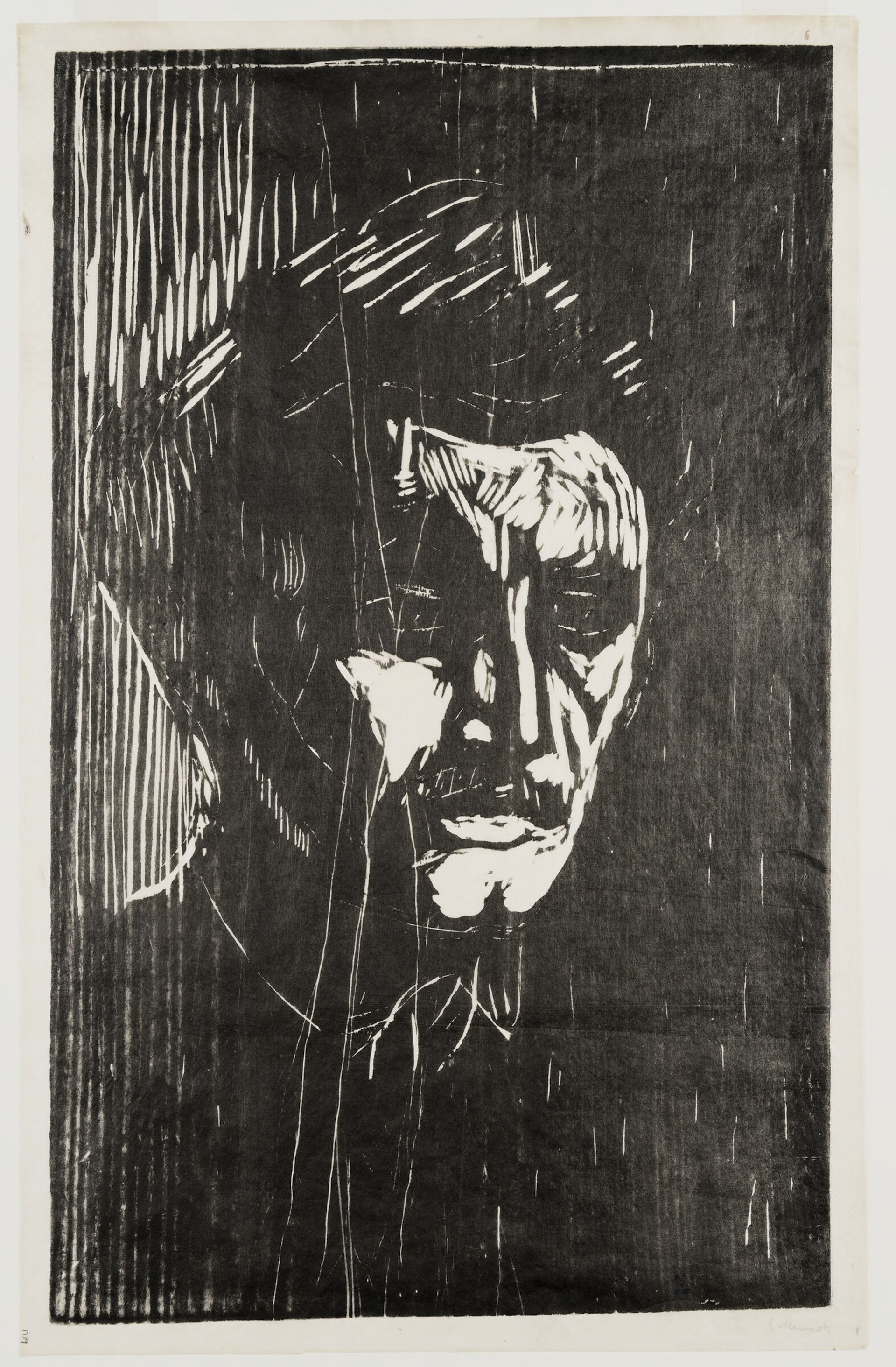

The latest bequest also includes a Jasper Johns 1982 lithograph and monotype, showing his so-called Savarin motif, depicting a coffee can with paint brushes, with an arm at the bottom that refers to the skeletal arm in Munch’s own 1895 self-portrait. The new bequest has a later Munch self-portrait, from 1911-12—a severe, vertical-lined woodcut on Japan paper.

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait, 1911–12. Woodcut with gouges on Japan paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

Though the couple made the initial collecting foray together, “the first Munch fan was Lynn”, says Marjorie B. Cohn, former curator of prints at the Harvard Art Museums, who first got to know the couple in the 1980s. “Phil eventually caught the Munch bug,” Cohn says, and “seeing that the prints were extremely varied, was determined to find the best ones and ignore the rest.”

The Strauses went beyond merely donating; over the years, they also advised Harvard on which Munchs to purchase. The museums now have a total of 142 Munch works, 117 of which were either donated or assisted in purchase by the Strauses, according to a museums spokesperson.

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones), 1899. Woodcut printed in orange, yellow, black and dark greenish blue on tan wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, The Philip and Lynn Straus Collection Photo: © President and Fellows of Harvard College; courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums

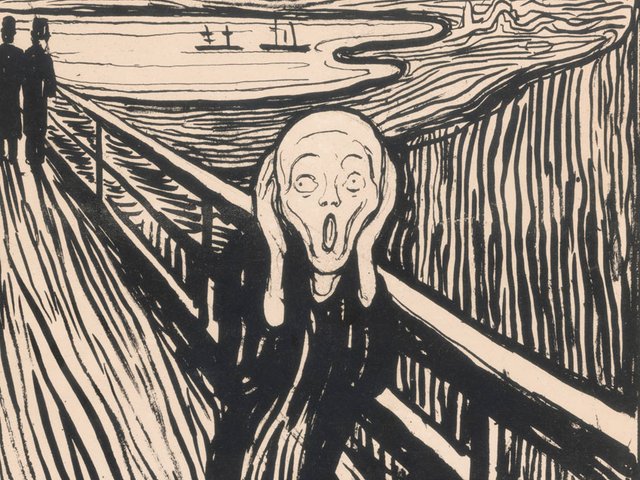

Other notable works in the new bequest include four impressions of Madonna, Munch’s erotic version of a devotional image that appears elsewhere across several media; and a late lithograph, Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine (1930), printed in black ink.

Both paintings and 33 prints from the new bequest will go on public display in a Harvard show opening 7 March. Edvard Munch: Technically Speaking features loans from Oslo’s Munchmuseet, the main repository of the artist’s work and legacy, including an oil version of Two Human Beings (The Lonely Ones) from around 1935, in which the daytime palette of the Straus version has shifted to phantasmagoric, and the order of the two figures is reversed.