Like relics of some medieval saint, brown fragments now lie in a dimly lit glass case in Ravenna. They are pieces of the skin of the poet and outrager of society, Lord George Gordon Byron, awaiting pilgrims in a brand new museum in the city where he spent most of his last years, with the last of his long parade of beautiful married women.

Ravenna, in Emilia Romagna in north-east Italy, is not short of tourist attractions. Its eight fifth- and sixth-century Christian buildings, with their dazzling mosaics, are on the Unesco world heritage list.

It also has the tomb, museum and many other sites associated with the great poet who arrived 500 years before Byron, Dante Alighieri. The famed author of The Divine Comedy arrived in Ravenna in 1319 as a political refugee from Florence, and died there two years later—Byron regularly visited his tomb, and ventured out into the beautiful pine forest by the sea where a rotting stump is still known as Dante’s oak.

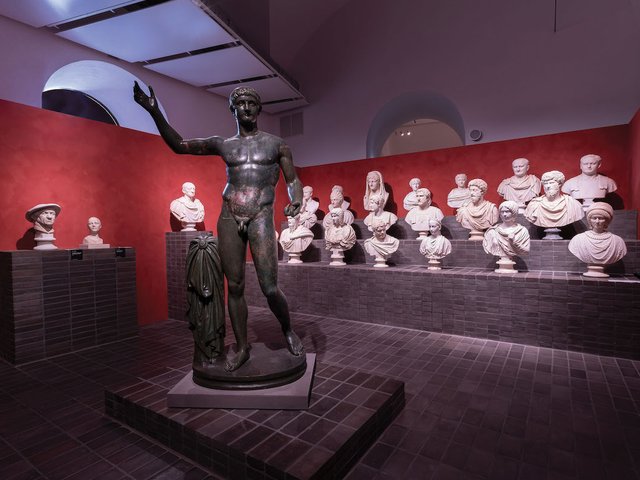

One of the rooms in the Palazzo Giuccioli

Courtesy of the Byron Museum

Diego Saglia and Gregory Dowling, professors at the universities of Parma and Venice respectively and academic advisors to the project, admit they have never yet met a tourist coming to Ravenna enquiring for Byron. They hope the museum, housed in the Palazzo Giuccili and filled with art, books and memorabilia, will change that—and make his work, now rather out of fashion, more read and revered.

How did Byron end up in Ravenna?

Byron left England for voluntary exile in 1816, famous as a poet but riding a tide of scandals. These revolved around, among other things, the cruelty with which he treated his wife Anna Isabella Milbanke, as well as his infamous public affairs with his half sister Augusta and Lady Caroline Lamb—who unforgettably dubbed him “mad, bad, and dangerous to know”.

After some time spent wandering Europe, he arrived in Ravenna in 1819, following Countess Teresa Gamba Guicciolo, a teenager he met at a party in Venice, who then had a husband almost 40 years her senior.

With typical Byronic swagger, the poet took rooms in the Palazzo Giuccioli, Gucciolo’s marital home, paying a hefty rent to her husband. He moved his menagerie of animals—including three monkeys and an eagle—into the cellars, though they didn’t always stay put. A visiting friend, the fellow poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, wrote: “I have just met on the grand staircase five peacocks, two Guinea hens and an Egyptian crane”.

Over two years he moved from the relatively modest ground floor into the grandest first floor rooms. In public he was Guicciolo’s recognised cavaliere servente, her devoted attendant at the opera and outings, a status recognised and tolerated in Italian society. The physical affair was conducted in the splendid frescoed spaces while her husband was out or taking a siesta, a perilous arrangement that inevitably came adrift.

Guicciolo formally separated from her husband and returned to her father’s home. Byron followed her, befriended her whole family, and in 1823 sailed to Greece with her brother Pietro to join the fight for Greek independence. He died in Missalonghi on 19 April 1824—less gloriously than the Byronic legend of fever. His cause of death, just like his hero Dante's, was probably malaria.

What can visitors expect to see at the museum?

The Byron museum building is now owned by a local bank, the Cassa di Risparmio di Ravenna, which co-funded the project with the city authorities and other cultural bodies.

The conversion, by architect Patrizia Magnani and designers Aurea Progetti, includes a separate museum on the first floor devoted to the local history of the Risorgimento, the revolutionary campaign to win Italian independence and a cafe. There is also a restaurant in the cellars once used to house Byron’s menagerie—and separately as a hiding place for rebel guns and headquarters for the Ravenna Byron Society.

A lock of Byron’s hair is among the exhibits

Courtesy of the Byron Museum

The Byron rooms also have spectacular interactive projections, including scenes specially filmed in Venice recreating his first meeting with Gucciolo. Text panels are in Italian and English, and although the soundscape in the rooms is Italian, an English version is available through an app.

When the two professors first saw the palazzo, which had served as government offices and a a barracks and then been abandoned for decades, it was virtually in ruins. It was impossible, Dowling recalled, to walk across the weeds and rubble filled courtyard. The conversion has taken 10 years, delayed by the pandemic and some surprising discoveries—a wall collapsing in what had been Byron’s study revealed frescoes commissioned by the poet, comprising versions of two Titian nudes.

Frescoes commissioned by Byron were discovered in what was his study

Courtesy of the Byron Museum

Although she married again, Gucciolo devoted the rest of her life to preserving Byron’s memory and the story of their love. As well as rare first editions and manuscripts, the display cases hold scores of mementoes she cherished or collected, including portraits, locks of his hair—with a few wisps of grey—and most terrifyingly intimate, those scraps of skin which she hoarded when he peeled after getting badly sun burnt.

“Would he have got bored and moved on, as he had so often before?” Dowling mused. “Time would have told, but time ran out for him.”

- The Byron and Risorgimento Museum, in the Palazzo Giuccioli, Ravenna, open Tuesday to Sunday, 10am-6pm