In the paintings and photographs gallery of the Jaipur City Palace hangs a portrait of the bejewelled Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, who founded Jaipur in 1727 and began building the palace that same year. A passionate astronomer with keen interests in architecture and literature, Jai Singh II is today remembered not just as a capable statesman and warrior, but also as a visionary patron who transformed Jaipur into a leading artistic centre of its time.

Next door, within the City Palace site, a new gallery marks the latest chapter of that legacy. The Jaipur Centre for Art (JCA), launched at the end of November, is a 2,600 sq. ft exhibition space for contemporary art—the only dedicated venue for such work in the city, and the first of its kind in an Indian palace still in use as a permanent residence.

“My family has long been a part of the contemporary conversation—this is a natural step,” says Padmanabh Singh, the head of the former royal family of Jaipur. (Although India abolished royal titles in 1971, some former royal families continue to use them unofficially.)

Maharaja Jai Singh II “set the tone for forward-thinking rulers of Jaipur”, Singh says—from the Maharani consort Gayatri Devi who rode horses and shunned head coverings at a time of “social conservatism” for women, to the “camera-toting, free-thinking Maharaja Ram Singh II who shot early selfies”. The JCA is, he says, “a chance to contribute to the contemporary cultural conversation of my city”.

The JCA was conceived in partnership with the Jaipur-based art adviser Noelle Kadar, who serves as its director. “Whenever people visit Jaipur they ask where the art galleries are,” Kadar says. “This city has immense craft heritage but lacks a contemporary art scene—yet.”

The opening group exhibition at the Jaipur Art Centre, A New Way of Seeing Lodovico Colli di Felizzano

Kadar’s vision for the JCA has been informed by her experience leading the Jaipur Sculpture Park, a public exhibition of contemporary sculpture and installations that opened its fifth edition last month in its spectacular new venue, the Jaigarh Fort in Amer. “Directing the Sculpture Park taught me how to consider what will, and will not, work in Jaipur,” she says. “That means thinking about what an audience expects to see in a traditionally beautiful, historic setting. And how to introduce into those spaces art that might not typically be considered beautiful. You can’t shove something down someone’s throat.” For Kadar, the JCA will provide a platform to recontextualise contemporary art. “When you see an exhibition in a Venetian palazzo done properly you come away thinking differently about the work,” she says. “I want our shows to achieve that.”

Commercial partnerships

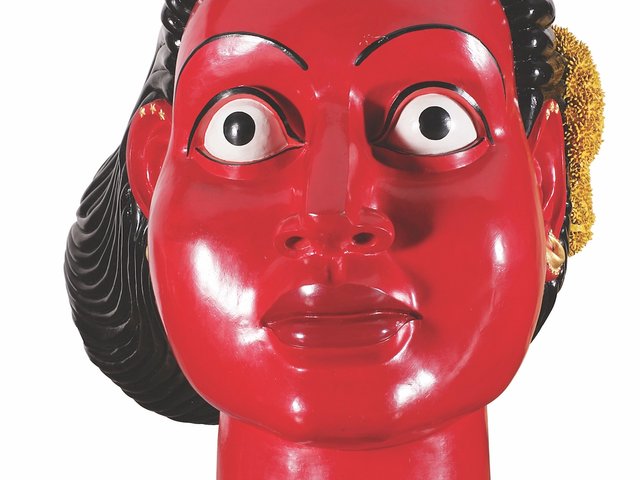

Kadar enlisted Peter Nagy, the current director of the Jaipur Sculpture Park and the founder of the Indian commercial gallery Nature Morte, to curate the opening show. Under Singh’s wish that the JCA exhibits both local and international art, Nagy has chosen works by eight artists—including a concave, reflective metal sculpture by Anish Kapoor, the red hue of which is mirrored in a photographic suite of bundled paper archives by Dayanita Singh, seascapes by Hiroshi Sugimoto and a colourful, blocky painting by Sean Scully—for A New Way of Seeing (until 16 March), an attractive and approachable show themed around shifts in perception.

Nagy says that he chose works that would “impress his peers” and also appeal to the tastes of the local audience. The show is both a curatorial and commercial endeavour, having been produced in partnership with three galleries—Nature Morte (New Delhi and Mumbai), Gallery Espace (New Delhi) and the international Lisson—to which the works on show are consigned. Kadar says that while JCA “does not sell art”, it can “make introductions”. The JCA’s main revenue streams, Kadar says, are through individual patrons and public sponsorship from organisations including Mash, a New Delhi-based foundation and digital platform for art, and the fine art and design publisher Skira.

For an art space in a major heritage site to open with a show curated by a gallery owner and in collaboration with several other dealers might seem an odd, even questionable choice, but it is being presented as the natural conclusion of an art ecosystem that for more than two decades has been largely built by the commercial sector. As Nagy says, “everything good in Indian art is because of private initiatives”.

Indeed, when Indian art attempts to engage with the public sphere it often finds itself at the behest of mercurial politics. The JCA is, after all, not the first significant contemporary art venture to open in Jaipur. Nagy, and many others, confer this title to the Jawahar Kala Kendra (JKK)—a cultural centre designed in 1993 by Charles Correa, which was reopened in 2015 under the directorship of the prominent Indian curator Pooja Sood. During Sood’s tenure, she transformed operations there and the centre staged ambitious and critically venerated shows including an exhibition on the Indian avant-garde film-maker Mani Kaul and a nine-day performing art festival. “They were the types of shows you would travel to,” says the Mumbai gallerist Priya Jhaveri.

However, in 2019, the JKK’s budget was slashed upon the election of a new chief minister for Rajasthan, the BJP’s Ashok Gehlot. “If you cut off my hands, how am I supposed to function?” Sood told The Hindu newspaper around the time of her departure.

Thanks to its position within the palace’s walls, the JCA will likely be safeguarded from such forces, and be bolstered by Singh’s backing and family ties: his mother, Diya Kumari, is a BJP politician serving as the deputy chief minister of Rajasthan. The royal seal of approval will also provide artists showing at the JCA with unparalleled access to the vast archives of his family that are currently only fully available to the in-house team managing Jaipur City Palace’s existing museums.

We want to assist artists in making something that really mattersNoelle Kadar, director, Jaipur Centre for Art

Open-ended residencies

The JCA will also soon launch a residency programme inviting Indian and international artists to Jaipur. Residency lengths will be “open ended”, Kadar says. “You can’t do anything properly in six weeks, we want to be flexible. That could even mean an artist coming for two-week periods several times over the course of two or three years.” There will be no obligation for resident artists to give the JCA work, or even to show work there, Kadar says. “We want to assist artists in making something that really matters. Not just the beginning of an idea for a body of work. We have a foundry, kilns, weavers—all the materials you could want are here. The residency will be about promoting artists being in Jaipur and engaging with its skilled artisans.” Moreover, she adds, it will encompass contemporary design practice, an industry thriving in both Jaipur and across India.

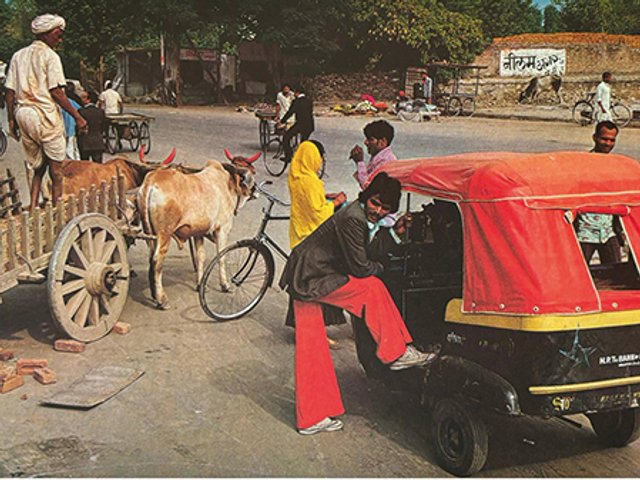

Jaipur’s world famous, centuries-old handicrafts industries owe much of their longevity to the visionary patronage of Jai Singh II. Three centuries later, those rich traditions continue to not only employ tens of thousands of its residents and help drive the city’s economy, but also draw in internationals like Kadar and Nagy, both of whom are originally from the US. “When I first came to Jaipur, I fell in love—there is this great sense of possibility here,” Nagy says. Kadar is similarly enthusiastic about her adopted city: “You can make anything here.”