Syrian heritage professionals are rallying to safeguard and restore the country’s ancient treasures following the fall of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime in December 2024.

“Unfortunately, the authorities and the transitional administration are still in the preparation stage and are not focused on the heritage file; it is currently not a priority,” Ayman al-Nabo, the director of the non-governmental organisation Idlib Antiquities Centre, says from Damascus. “On the other hand, civil society organisations dedicated to preserving heritage are intensifying their efforts and remain on high alert to assess the current state of archaeological heritage and protect sites.”

After Assad’s regime collapsed, heritage professionals quickly organised, forming a forum with around 200 people on WhatsApp to exchange information in real time and co-ordinate efforts, Nabo says. Teams were dispatched to assess the conditions of museums and sites where they were accessible.

In the turmoil that followed Assad’s exit, the Institute of Archeology in Damascus Citadel, an 11th-century building, was looted and set on fire, according to Nabo. The museum on Arwad Island, off Syria’s western coast, was also ransacked, he says: “We don’t have all the information yet, but we think 38 objects were stolen from the Arwad museum.” He notes that both sites, along with all other accessible museums, have since been secured and are now under guard.

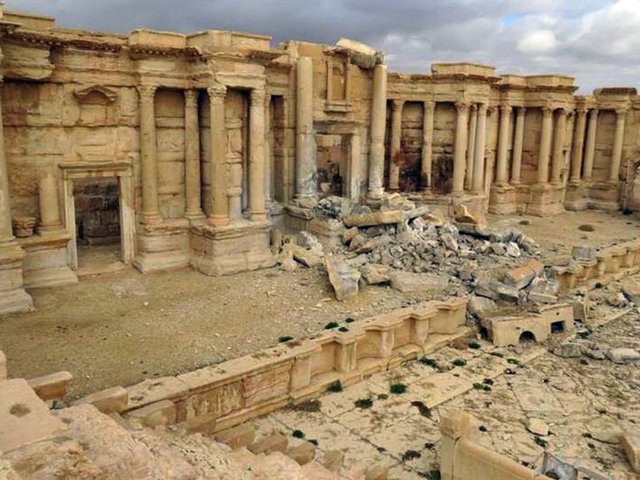

Palmyra was hit by airstrikes during the most recent conflict Photo: Ammar Kannawi

The cultural association Syrians for Heritage reported last December that the city of Aleppo, home to a Unesco World Heritage Site and the Aleppo Museum, was “preserved without any damage”. It also noted that Aleppo Citadel, which had become a site of celebration for people, was under the “management of military operations” and remains inaccessible. Meanwhile, following reports of an attempted looting at Damascus Museum, Nabo’s team inspected the site and found “the museum has not been subjected to any vandalism or theft”.

The war, which erupted in 2011, has taken a heavy toll on Syrians, displacing more than 14 million people and killing at least 580,000, including an estimated 300,000 civilians. Syria’s ancient heritage was also targeted. In Aleppo alone, a 2017 Unesco report estimated that 60% of its Old City was severely damaged, with 30% completely destroyed. Among the militant groups that emerged during the war was Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which played a key role in defeating Assad’s forces in December and has now established itself as Syria’s de facto rulers.

‘Extreme chaos’

Protecting the country’s archaeological sites is a struggle as they continue to be looted. “In the Hama countryside [around 200km north of Damascus] there is a state of extreme chaos and widespread illegal excavations of sites and hills,” Nabo says. He attributes the vulnerability of Syria’s archaeological sites to the lack of security and guards, as well as their sheer number—around 10,000, by his estimate. He stresses, however, that illegal excavations have been ongoing since 2011.

A report published last month by Palmyrene Voices, an initiative launched in 2020 by the NGO Heritage for Peace, highlights three looting cases in Palmyra. “It is obvious that looting is increasing [across Syria],” Isber Sabrine, the president of Heritage for Peace, tells The Art Newspaper, confirming that his team has observed illegal excavations since the regime change. “The economic situation in Syria is very bad, and people loot because they don’t have any resources,” he explains.

The majority of the Palmyra Archaeological Museum's collection was transferred to Damascus prior to Isis attacks on the ancient city in 2015, however, what is left in the museum has been damaged. According to a January report by Palmyrene Voices, the museum's structural integrity is also compromised © Ammar Kannawi

The report offers an in-depth examination of the area, including its museum, castle and archaeological sites. It documents the damage inflicted by various entities over the years, including Islamic State (Isis)and the Assad regime, concluding that most of the damage occurred prior to December 2024.

One of the “extensive clandestine excavations” identified in the report took place at the site of Camp Diocletian, where architectural remains—including stone foundations and decorations from funerary beds—were exposed. The excavation site was near a military fortification with direct view of the area.

Sabrine says international sanctions have severely impacted the country, leaving no funds for heritage and neglected sites. “The Syrian heritage sector depended on international aid, universities and projects in order to survive,” he adds. Sabrine remains hopeful that Syria can emerge with a unified government, improved security and the lifting of sanctions, which will provide the necessary support for the cultural sector to begin its recovery.

The report also noted that the Palmyra Archaeological Museum, which had evacuated some of its collection to Damascus in 2015 before Isis took control of the area, is closed and protected by guards and local volunteers, without support from the new administration.

“We will survey all the damage in different archaeological areas; we have a three-year plan for this,” Anas Zaidan, the director general of Syria’s Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums (DGAM), which is responsible for the country’s antiquities, told local and international heritage experts on 20 January during a webinar organised by Blue Shield and Heritage for Peace.

Zaidan presented an ambitious blueprint for preserving Syria’s heritage, which includes rehabilitating museums and archaeological sites, establishing museums in areas such as Ebla, Ugarit and Mari, and digitising manuscripts.

Zaidan also plans to work closely with Unesco to remove northern Syria’s archaeological sites from its List of World Heritage in Danger. (In 2013 Unesco placed all six of Syria’s World Heritage Sites—the Ancient City of Damascus, the Site of Palmyra, the Ancient City of Bosra, the Ancient City of Aleppo, Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din, and the Ancient Villages of Northern Syria—on its endangered list.

However, Zaidan highlighted that his team is in desperate need of expertise and equipment, including cameras and monitoring devices.

A spokesperson for Unesco says its Beirut office has been tasked with exploring technical assistance for heritage conservation. A team is scheduled to travel to Damascus this month to meet with “relevant experts and technical entities dealing with cultural heritage, archives and museums”.

International support

“Syria is a very challenging country to work in: the fractured political situation, competing interests, sanctions and high security risks mean it’s very difficult to be able to provide aid directly,” says Emma Cunliffe, who is part of the Blue Shield international secretariat. “However, difficult isn’t the same as impossible, and we’re determined to work to support Syrian heritage professionals in preserving their heritage.”

Cunliffe says that, following information-gathering missions in Syria last year, in partnership with Heritage for Peace, Blue Shield is applying for funding to provide support to sites and professionals in the country. It is also aiming to have a representative on the ground soon.

Their webinars, she says, have been an important first step in that direction, enabling a cross-section of Syrian society to communicate with the international community about the challenges they face and the support required. “We heard from speakers across the country, in areas of different political control, all united by the same goal, despite facing years of working in extremely challenging situations. They are still deeply committed,” she says.

Palmyra Archaeological Museum © Ammar Kannawi

Graham Philip, a co-investigator on the multi-institutional project Endangered Archaeology in the Middle East and North Africa (EAMENA), who attended the webinar, says his team is exploring a collaboration with the reconstructed DGAM to train staff in digitally recording data. “What’s lacking is a knowledge of the condition of sites across the country,” he says. “That’s what you might call baseline data, because you can’t start deciding what is a priority until you know what the damage is and how bad it is.”

Since 2016, Philip and his team have recorded thousands of historic sites in Syria using satellite imagery and archaeological research. He says the project can support the country’s antiquities authorities to create a national database based on their system, which would eventually be managed and owned by Syria. At present, there is no single database that holds all of Syria’s sites. Data gathered by EAMENA could also be used to track looting.

John Darlington, the director of projects at the World Monuments Fund (WMF), was around ten miles from the Syrian border in Mafraq, Jordan, when the Assad regime fell. He was visiting a group of displaced Syrian stonemasons who had participated in a WMF training programme launched in 2017.

“The whole idea of training them was, when the conflict ends, you’d have these skilled people who could go back into Syria and help rebuild the cultural heritage,” Darlington explains. “It was a really moving moment,” he adds as, for the first time in years, the stonemasons could imagine working in their own country. The programme has trained 40 Syrians in stonemasonry, a vital skill for restoring the country’s historic sites.

Darlington says that the WMF is collaborating with international partners to ensure they are ready to support Syria’s heritage workers when the time is right. He notes that, in post-conflict situations, priorities often lie elsewhere, but assisting local communities in rebuilding their cultural heritage is crucial: “Don’t underestimate the value of cultural heritage in terms of rebuilding nations because people really value it and it’s part of what gives them hope.”