Colin Renfrew was regarded by many as the world’s pre-eminent living archaeologist. Inspired by the beauty inherent in past material expressions of the human condition, he became fascinated by the parallel lines he saw in understanding ancient and modern worlds through art. “Figuring out who we are—trying, that is, to understand what it is to be human,” he wrote in a book about art and archaeology, was a question that drove his life’s work, which began with hard questions and hard science in a then almost moribund discipline, and through a combination of chance, new discoveries and brilliant theorisation led to a reinvigorated archaeology with much to say to the modern world.

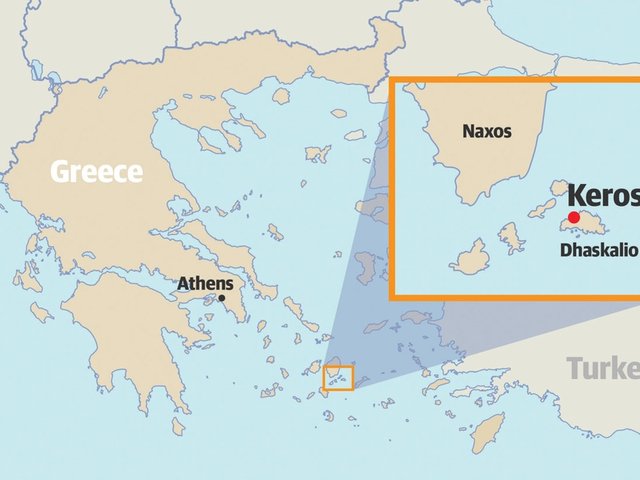

He was born into a middle-class family in Stockton-on-Tees in the north of England, and lived his early years in Welwyn Garden City. Visits to Paris meant he learned French and “got to know the Louvre very well”; one of its more enigmatic exhibits, a large prehistoric marble head of simple and elegant form, said to be from the island of Keros in the Cyclades, subsequently loomed large in his life’s course. After national service he went to the University of Cambridge to study natural sciences, but after the first year was persuaded to switch to archaeology after discussing the option with Glyn Daniel, then editor of Antiquity. In retrospect, given his interest in the ancient world (and antiquities), and summers spent on archaeological digs, the change seems natural. After graduating, he decided to begin a PhD looking into the rather obscure third millennium BC in the Cyclades. In this he was prompted by Christian Zervos’s 1957 book L’Art des Cyclades, itself born of the influence Cycladic sculpture had begun to have on 20th-century art, inspiring figures such as Constantin Brâncuși and Amedeo Modigliani.

Renfrew’s science background however came to dominate his work in the 1960s and 70s. Feeling dissatisfied with prevailing modes of explanation in archaeology that relied upon largely subjective criteria, in a series of papers in the 1960s he embraced new scientific approaches, including the elemental characterisation of materials, which could explain matters of provenance of source material and technology, and radiometric methods of dating, especially radiocarbon. He was the first archaeologist to grasp the true significance of the calibration of radiocarbon dates, which produced what he called a “fault line” across Europe. His 1973 book Before Civilisation: The Radiocarbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe showed that all the old explanations for cultural change in the past were not only deficient but untenable as the chronologies of different archaeological cultures had changed.

A radical new approach

In 1967 Renfrew spent a term at the University of California, Los Angeles, and encountered Lewis Binford, the earliest proponent of a new movement in archaeology that embraced the sciences and statistics, and sought to establish theory close in nature to the laws of natural sciences. Renfrew drew heavily on this new approach, and indeed became one of its key exponents, for his seminal 1972 work The Emergence of Civilisation, a monumental and enduring publication widely regarded as one of the most significant books ever published in archaeology. In it he not only sought to explain developments in the Aegean in their own terms (rather than as a result of contact with other areas) but he also went about applying the principles of the “new archaeology” systematically to an entire time and place in a way not attempted before and yet to be matched in any meaningful way.

Renfrew became lecturer then reader in the dynamic department at Sheffield before becoming professor of archaeology at Southampton in 1972. He was elected to the Disney professorship of archaeology in Cambridge in 1981, a post he held until his 2004 retirement. He was master of Jesus College from 1986 to 1997, hosting the Queen for the college’s quincentenary, and he was founding director of the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research at Cambridge. The McDonald Institute was conceived as a research institute for archaeology at Cambridge, embracing archaeological science through the establishment of a number of laboratories, as well as forming the home for the growing number of researchers associated with the department of archaeology. Today the McDonald Institute is one of the largest and most successful such institutes in the UK.

Orkney to the Med

Besides his research on Greece and in archaeological theory, Renfrew was widely active in the archaeology of Prehistoric Europe (and Britain in particular) as well as worldwide. The 1970s saw a dizzying series of publications that pushed the boundaries of the archaeological research agenda. He undertook excavations at Quanterness and elsewhere on Orkney, beginning a lifelong association with those islands. However, it was the islands of the Cyclades in Greece that maintained the strongest attraction for him. He excavated on the tiny islet of Saliagos between Paros and Antiparos in the 1960s, and, after excavations on the northern mainland at Sitagroi, he turned in the 70s to the site of Phylakopi on Melos. Here he deployed a panoply of scientific and landscape techniques with the aid of his students (John Cherry in particular), turning the archaeological project from a limited excavation into an innovative landscape analysis. The resulting publication in three volumes was deeply influential on landscape archaeology in the Mediterranean in general.

His was also a strong voice against the decontextualised “art” of looted objects and the market for them among museums and collectors. Elevated to the peerage in 1991 as Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn, he became active in parliament on matters of cultural heritage legislation and practice, in particular the problems of looting and the provenance of artefacts in museums. In 1996 he established the first academic unit to study the illicit trade in antiquities (run by Neil Brodie and Jenny Doole), with its own publications, which won the European Archaeological Heritage Prize in 2004. He was active in the return of looted antiquities to Greece, including the return of two important Cycladic artefacts from Germany in 2014.

Spectacular finds in the Cyclades

Renfrew was energetic and prolific in many other areas of research, including archaeogenetics and the relationship between archaeology and language. He developed “cognitive archaeology” as his own distinctive evolution of the new archaeology of the 1960s and 70s; he is synonymous with other approaches such as peer polity interaction or material engagement theory. Awarded the Balzan Prize in 2004, he elected to undertake a major new project on the uninhabited Cycladic island of Keros, where he had previously excavated for a short period in 1987, but had first visited as long ago as 1963. This research initially ran for three years (2006-08), with further work (co-directed with others) in 2012-13 and 2015-18. The excavations and surveys of these programmes came to dominate his post-retirement research output, and the spectacular finds and their remarkable interpretation (“the world’s earliest maritime sanctuary”) cemented his place as the foremost archaeologist working in Greece. In many ways this concentration on the Cyclades and on solving the mysteries of Cycladic sculpture over recent decades is a fitting conclusion to an interest sparked by that remarkable sculpted head in the Louvre many years before, and the early publication of Zervos.

Renfrew had a long-standing interest in Modern art. His interest went far beyond those artists whose work was influenced by Cycladic sculpture. He was deeply moved by the works of John McLean, and as master of Jesus College he instituted “Sculpture in the Close”, which eventually led to works by Antony Gormley, Eduardo Paolozzi, Barry Flanagan, John Bellany, Alison Wilding and Richard Long gracing the college, initiating a long and successful partnership between the worlds of art and academia. In his 2003 book Figuring It Out he drew these two worlds together, arguing that the processes of interpreting and understanding Modern art, and our relationship to it, were analogous to the processes of interpreting archaeological evidence, and that one could usefully inform the other.

The passing of Colin Renfrew leaves a void in the archaeological world, but his was a long and successful life that left little undone. His archaeological textbooks are read by students worldwide (in multiple languages) and his theoretical approaches are still discussed in archaeology’s different sub-disciplines. In the McDonald Institute he has created a lasting legacy for generations of researchers, and in the Aegean his influence is incomparable. The work on Keros will continue for the next decade at least, but has already rewritten, for the second time, the story of the emergence of civilisation in the Aegean. Those of us who had the privilege of working with him must now carry his enormous legacy forward.

Andrew Colin Renfrew; born Stockton-on-Tees 25 July 1937; married 1965 Jane Ewbank (one daughter, two sons); died Cambridge 24 November 2024