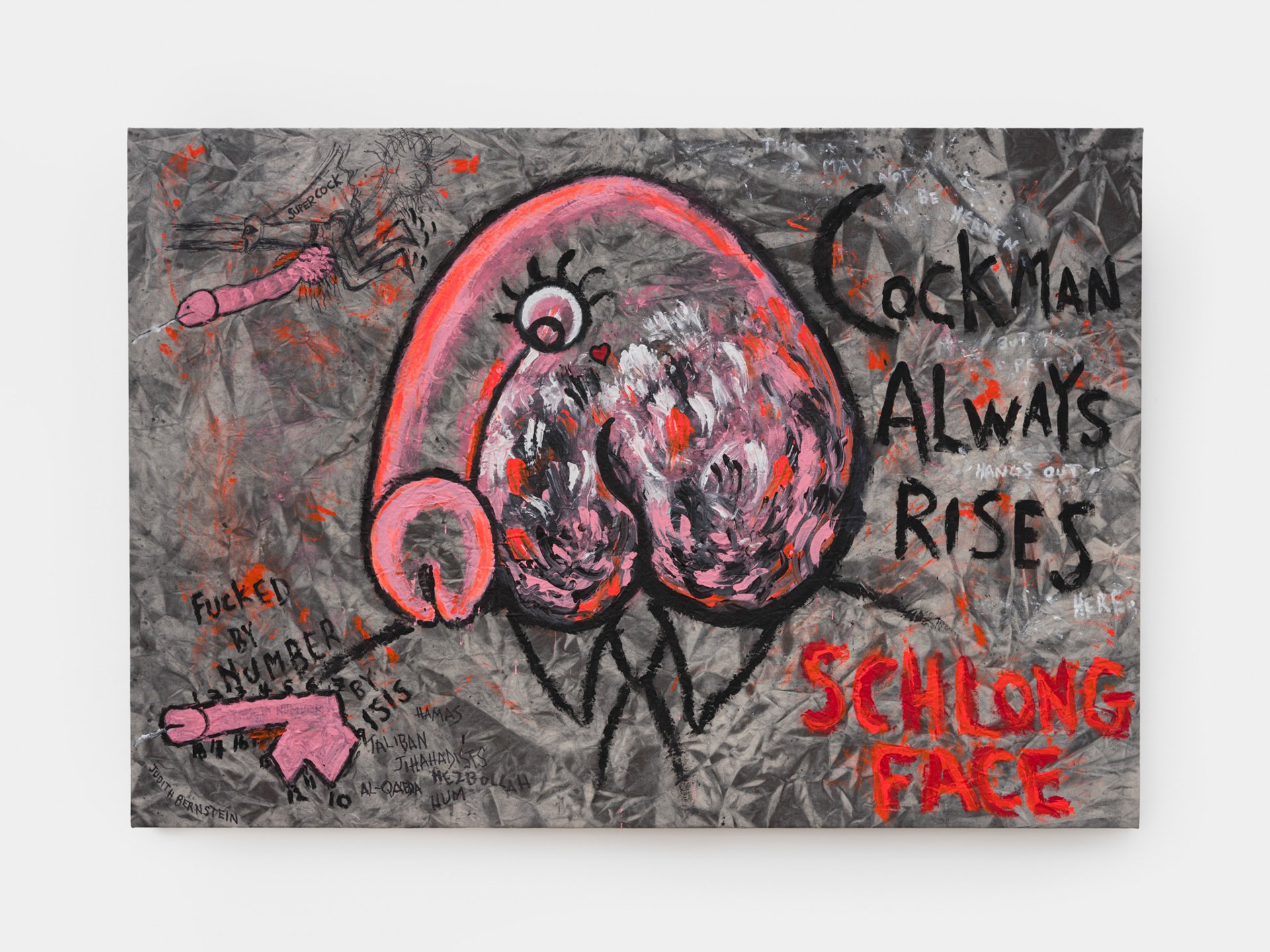

Journalists have drawn several parallels between the freshly re-inaugurated US president Donald Trump and the late George Wallace, the authoritarian segregationist who won his first term as governor of Alabama in 1963. But it takes an artist—specifically, the 82-year-old firebrand Judith Bernstein—to connect the two men by transforming both into Cockman, a satirical superhero bearing, as Bernstein describes in an email interview, “a literal cock for a head (a dickhead!) with a schlong nose and a dapper tie”. Frustratingly, the image is no less a dare to censors today than it was in the 60s, an American decade ruptured by intense and sustained conflicts over civil rights, the Vietnam War and much more.

Judith Bernstein, Cockman Always Rises – Schlong Face (2016) © Judith

Bernstein. Courtesy of the artist and Kasmin, New York

The Trumpian version of the character appears in the 2016 painting Cockman Always Rises—Schlong Face, on view in a survey of Bernstein’s career at New York’s Kasmin gallery (until 15 February). The exhibition, Public Fears, reminds viewers that the artist has been making no-holds-barred work about divisive political issues for nearly six decades. It has sparked considerable interest. A by-invitation walkthrough of the show, pointedly held on 6 January—the anniversary of the 2021 Capitol Hill riots—attracted cultural luminaries ranging from David Byrne, the frontman of the Talking Heads, to Matthew Higgs, the director of the non-profit White Columns. Meanwhile Bernstein has a solo show at the Kunsthaus Zurich in 2026.

Yet she has had to fight like mad against censorship to reach this point. She says her career was “essentially halted” in 1974, when the Civic Center Museum in Philadelphia barred Horizontal (1973), a large-scale charcoal drawing of a “phallic screw”, from an exhibition of 86 female artists. The censors “branded me as a pariah”, she adds.

Judith Bernstein says she feels the re-election of Donald Trump “stirs up new anxieties around our freedom of speech”

Photo: Charlie Rubin. Courtesy of Kasmin, New York

Although it took 50-odd years, Bernstein thinks she had the last laugh: the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York acquired Horizontal in 2023. Yet the ban that threatened her livelihood in the 70s has a renewed resonance lately. “In some ways, that feels like the distant past, but on the other hand, the re-election of Trump stirs up new anxieties around our freedom of speech,” she says.

Past is prologue

Progressive and boundary-pushing voices in the US have felt the heat escalating since Trump’s latest victory at the polls. The House of Representatives approved a bill in late November that would empower the new administration to designate a non-profit as a “terrorist organisation”—and so revoke its tax-exempt status—based on troublingly broad standards, according to the American Civil Liberties Union.

In January, Texas police seized photographs by the celebrated artist Sally Mann from a show at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth after a complaint, seemingly provoked by articles by a conservative activist, that they constituted child pornography. A spokesperson for Gagosian, which represents Mann, declined to comment, but the museum pointed out in a statement that “these [works] have been widely published and exhibited for more than 30 years in leading cultural institutions across the country and around the world”.

The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Texas Photo: Carol M. Highsmith via the Library of Congress

In the same month, a joint survey commissioned by the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), Pen America and the Artists at Risk Connection found that 55% of AAMD respondents felt censorship was “a much bigger problem for museums today” than ten years ago.

The present has disturbing echoes of earlier restrictions on expression. Bernstein calls the 1960s “an obvious parallel”. Shannon Jackson, who chairs the history of art department at the University of California at Berkeley, tells The Art Newspaper that “analogies could certainly be made to the Nazis’ early 20th-century banning of so-called ‘degenerate art’”, as well as “the enforcement of only certain approved art forms and styles” by communist regimes. Equally alarming, she adds, are contemporary mutations enacted by autocrats worldwide, such as the scapegoating of queer, migrant and other minority communities.

Jackson is one of the four scholars heading up a multi-year, multi-institution programme called A Counter-Imaginary in Authoritarian Times, which aims to combat censorship and strongman politics using the arts and literature. Funded by a $2.6m grant from the Mellon Foundation, the initiative will run the gamut from workshops and conferences to performances and publications. Debarati Sanyal, the director of Berkeley’s Center for Interdisciplinary Critical Inquiry and another of the project’s leaders, says one of its goals is “to open alternative visions of what a just and livable collective future looks like” as a counteroffensive to authoritarianism’s “capacity to stoke fear through imagery”.

Although direct bans of works of art grab headlines, “resigned acceptance leads to normalisation,” Jackson warns. “Concern about being censored leads us to censor ourselves.”

Jackson, Sanyal and Bernstein agree that coalition building will be crucial for artists and institutions facing censorship in the years to come, both domestically and abroad. Bernstein learned this lesson first-hand as one of 20 women artists who founded the non-profit AIR (Artists in Residence) Gallery in Manhattan in 1972, “when [they] had no platform”. One of her mantras—and its focus on plurality—is proving as relevant as ever: “If we don’t voice opposition, we submit.”