“Photographer of the Local Sun”, reads an advertisement that the early-20th-century photographer Karimeh Abbud (1893-1940) placed in El-Carmel newspaper in 1924. “The only local woman photographer in Palestine. She learned this fine art from a well-known photographer and has specialised in work for women and families, with reasonable prices and extra professionalism. Requests accepted from women who prefer to be photographed in their own homes, any day except Sunday.”

A facsimile of this ad is on the wall of Abbud’s current solo exhibition at Tel Aviv's Eretz Israel Museum, Karimeh Abbud: Sacred Souvenirs (until 11 April), highlighting her position as one of the earliest female Palestinian photographers. Displaying approximately 100 local landscapes with Christian significance and around 15 photographs of daily Palestinian life, it is the largest-ever Abbud exhibition in Israel and was in planning stages before the current war. Following renewed interest in Abbud over the past two decades, solo exhibitions of her work have taken place at Darat al Funun in Amman in 2017 and at the Beirut Image Festival in 2019, and three documentary films have been produced about her.

Karimeh Abbud, Jerusalem, Church of the Holy Sepulchre, 1920-40 Bouky Boaz collection

Abbud’s photographs stand apart from those of the foreign photographers who began flocking to the Middle East soon after the invention of photography. “Without these photographs taken by Karimeh Abbud, we wouldn’t have these views of villages,” says Mustafa Kabha, a history scholar focusing on Palestinian people in the modern era at the Open University of Israel, in a short film produced for the exhibition. “We see less of an artificial picture and more of a true image that expresses the identity of this place.”

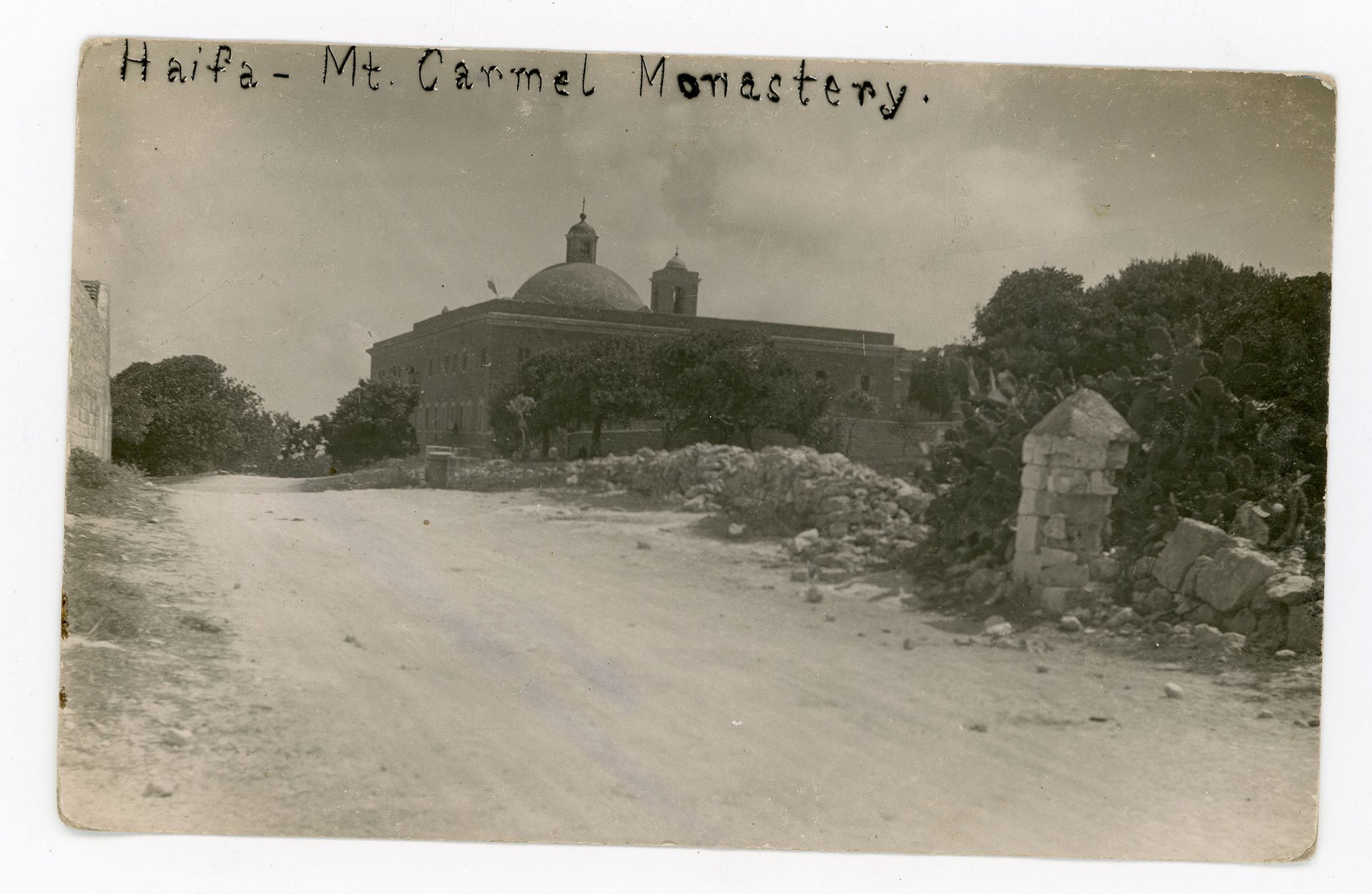

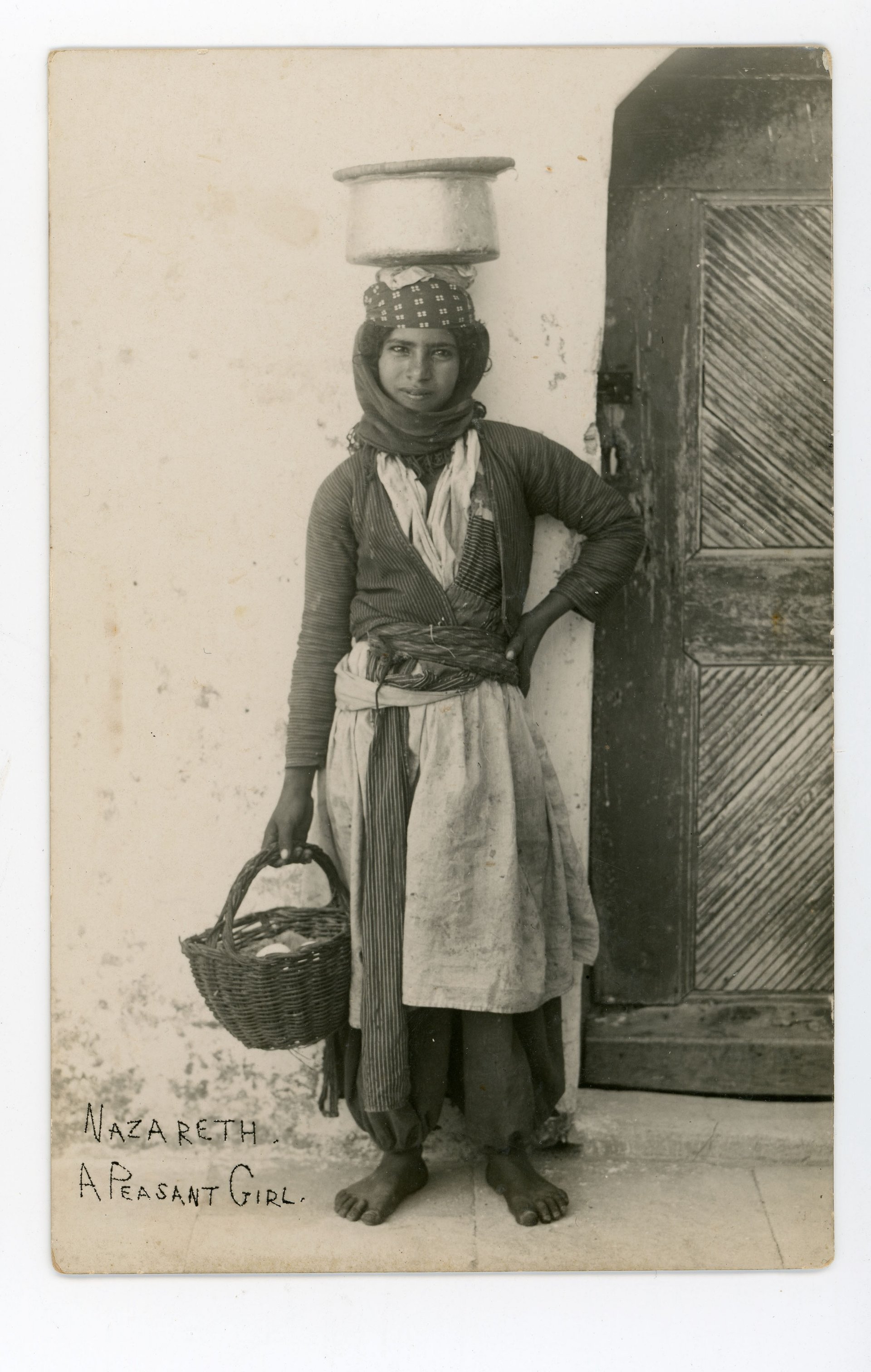

She photographed sights relevant to the local clientele—such as Nazareth’s threshing floor, a significant communal gathering space. She also took pictures of holy Christian sites and marketed them to visitors making pilgrimages to the region, in souvenir postcard packs at a dedicated stall in Nazareth.

Karimeh Abbud, Haifa, Mount Carmel Monastery, Stella Maris, 1920-40 Bouky Boaz collection

Abbud was born into a Palestinian Christian family of six children and her father, Said, was a Protestant minister, with her mother, Barbara, working as a teacher. Her father gifted her a camera for her 17th birthday, and though it is unknown who trained her, she took on the technically challenging work of photographing landscapes (often driving herself to these locations, sometimes in difficult travel conditions). The stamp that she imprinted on her prints reads: “Miss Karimeh Abbud, Photographer Nazareth.”

One of the research discoveries made by curator Guy Raz and presented in this exhibition is her contact with the American photographer Adelbert Bartlett, who photographed her entrepreneurial postcard stall (several of the postcards visible in the stall were successfully identified, with some included in the exhibition). Bartlett visited the Middle East several times between 1925 and 1934 as director of the Near East Relief Fund in Los Angeles. His archive, held at the University of California Los Angeles, contains materials related to Abbud—including a postcard she sent him in December 1929, wishing him a happy Christmas and bright new year.

Karimeh Abbud, Nazareth, Casa Nova Hospice, postcard #8 from the Souvenir of Palestine booklet, 1920-40 Bouky Boaz collection

Fast forward nearly a century, and there is complexity surrounding the timing and location of Abbud’s exhibition. “It’s the right thing to do, politically,” says Raz, the photography curator at the Eretz Israel Museum, of mounting the exhibition during the current war. “There’s a different, repressed narrative here.” Compounding this poignancy, the original prints are all loaned from an Israeli private collector, Bouky Boaz, who holds one of the largest collections of Abbud’s work at around 300 photographs. (The Eretz Israel Museum also has around 20 original prints by Abbud in its permanent collection.)

In preparing for the exhibition, Raz and Boaz met with a member of the photographer’s family, D’aibes Abbud (whose great-grandfather Salim was Karimeh Abbud’s uncle). After speaking to them about her, he directed them towards the building where Abbud lived and worked, images of which are included in the exhibition. When D’aibes Abbud spoke at the exhibition opening in December, he expressed gratitude that “in days such as these, when hatred is rampant and the air is saturated with hatred, someone sees fit to take on the subject of a female Palestinian photographer”.

Karimeh Abbud, Nazareth, village girl carrying a basket of eggs, 1920-40 Bouky Boaz collection

Despite two decades of renewed study of Abbud, there are still basic disagreements about her biography and the scope of her work (even her Wikipedia entry is rife with contested information). This is reflective of regional tensions, which can lead to a lack of cooperation among scholars. Raz argues through the works presented in this exhibition that Abbud’s focus was on landscapes relevant to Christianity. Some Palestinian researchers as well as Rona Sela of Tel Aviv University, who specialises in the visual historiography of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, claim that Abbud’s photographic lens was more focused on local daily life as part of an effort to illustrate the rich community life of her people.

Exhibitions such as Karimeh Abbud: Sacred Souvenirs create opportunities to see and discuss her work, hopefully leading to a truer understanding of her photographs and their meaning.

Karimeh Abbud, Tiberias, view from the Sea of Galilee, postcard #26 from the Souvenir of Palestine booklet, 1920-40 Bouky Boaz collection

- Karimeh Abbud: Sacred Souvenirs, until 11 April, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv