In 2020, the Brazilian artist Igi Lola Ayedun began Hoa in São Paulo, a residency programme that soon became the city’s first Black-owned gallery. Dedicated to non-white artists and Global South knowledge forms, Hoa quickly garnered an international platform and helped to launch the careers of a new artist cohort better representative of Brazil’s racial diversity.

In 2020, Igi Lola Ayedun launched a residency programme that developed into Hoa, São Paulo's first Black-owned gallery Wallace Domingues

Five years on, Hoa is moving away from its commercial roots and has relaunched as the non-profit Hoa Cultural Society, an institution that will encompass an international artist residency, prize-granting body, free online art school and a venue for exhibitions, performances and other cultural activities.

Brazil is still a colonial country. I had to work much harder to convince collectors that the art I was showing was not second rateIgi Lola Ayedun

“In truth, Hoa was never a traditional gallery; it always operated more like a non-profit institution,” Ayedun says. She conceives of Hoa’s rebrand as a way for it to better address the issues of structural inequity that it was formed in response to.

Hoa, Ayedun explains, began in the wake of the former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro gutting the culture ministry and cancelling state-sponsored affirmative policies supporting Black and Indigenous people, following his inauguration in 2019. “As Covid-19 hit, I saw artists from my community not being able to pay their bills while the global art market was booming," she says. "I wanted to find a way to funnel some of that money into helping my peers.”

Entrenched barriers

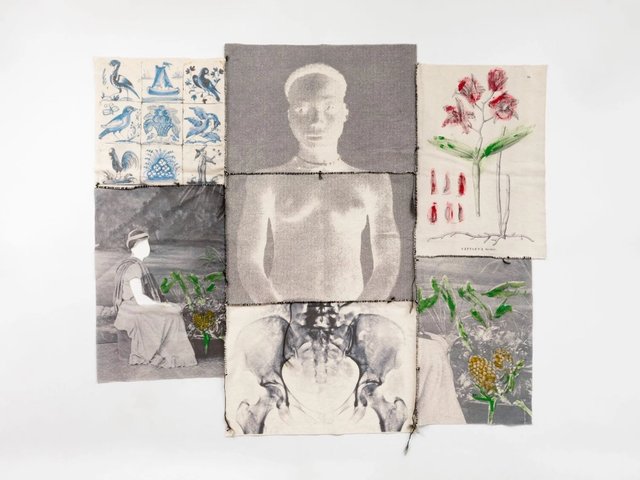

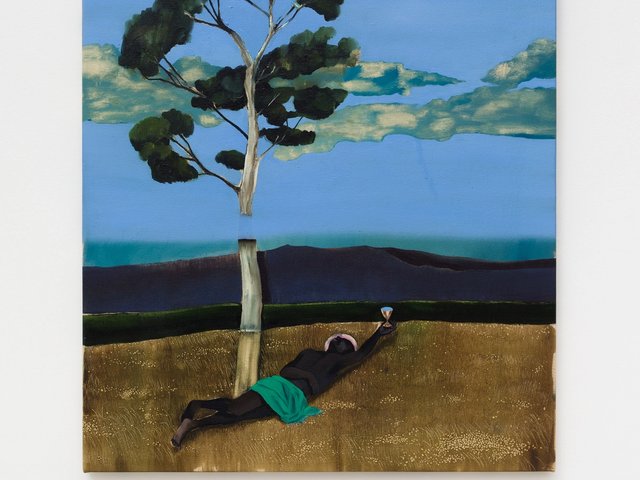

Upon entering the art market, Ayedun quickly realised how deeply entrenched the barriers preventing non-white artists from achieving success in Brazil are, and that Hoa would need to provide essential services to its artists, many of whom came from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This included paying their studio rent, supplying materials and equipment, and providing close mentorship to artists who “had not been formally trained in art school and were unable to navigate within the traditional art world”.

Hoa Cultural Society's open-plan space in São Paulo’s Barra Funda neighbourhood will be an incubator for underserved artists Wallace Roberto

Structural issues of race as well as gender also impacted Ayedun’s ability to act as a dealer, she says. “Brazil is still a colonial country. I had to work much harder to convince collectors that the art I was showing was not second rate, that just because it uses a different set of cultural references doesn't mean it has less value than work rooted in the Western canon.”

Ayedun turbocharged Hoa’s first years by looking beyond Brazil’s domestic collector base. “I knew the programme would be more readily received abroad; that’s why I did so many art fairs—around 10 a year”, she says of Hoa's rapid growth. “It was a business strategy, not magic: the conversion of a stronger currency, dollars, into a weaker one, reais.”

Sustainability focus

In its first years, Hoa exhibited several artists who are now gaining a global presence, such as Gabriel Massan and Rafaela Kennedy. It also won best stand prizes at art fairs including Milan’s Miart and Artissima in Turin. But as many a fledgling dealer can attest, running a young gallery and exhibiting internationally at art fairs takes its toll: “It was exhausting; I couldn’t continue at that pace,” Ayedun says.

Hoa will now attempt to restructure Brazil's art world in “a more impactful and sustainable way; it has to go beyond a fair booth”. Retaining its large, open-plan space in São Paulo’s artistic Barra Funda neighbourhood, Hoa Cultural Society will act as an incubator for artists for whom established institutions are unsuited. “Brazil’s institutions are designed for artists who are already in the gallery system and have launched their careers,” Ayedun says.

Brazil’s institutions are designed for artists who are already in the gallery system and have launched their careersIgi Lola Ayedun

Hoa will launch a free online school and a programme to professionalise artists, teaching classes like how to apply for funding. Alongside this it will establish three annual awards, including one for mid-career women artists to produce a curated publication of their work, as well as a grant for a young Brazilian artists from “marginalised communities” to provide financial grants and mentorship “rooted in decolonial and Black feminist perspectives, to help dismantle the Eurocentric art canon and promote social equity”, according to a press release.

An international residency will also be established, in collaboration with the Institut Français, the French Embassy of Brazil and the French Ministry of Culture to send Brazilian artists for a 10-week long programme at the Dos Mares research centre in Marseille and to receive francophone artists in Brazil.

In addition, this spring, during São Paulo art week (2-6 April), Igi in collaboration with Metro Arquitetos will launch a floating art pavilion on the city’s Pinheiros River, commissioned by Aguas Abertas and curated by Gabriela de Mattos, the winner of the Golden Lion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, and the art critic Paula Alzugaray. The project is sponsored by the culture ministry and SABESP, the state’s water company.

Hoa will show around three exhibitions a year. Now relieved from the pressure of selling, these shows will include more digital, conceptual, new media and performance art than Hoa’s commercial programme. “I want Hoa to be a lab, a place where artists can experiment and fail. During my time in Europe, I realised how experimentation is a given for most young artists. But here in Brazil, who can afford to experiment? So many Black and Indigenous artists are feeding their whole families from their art; they simply can’t take risks as easily.”

Funding for these projects will come from both private and corporate donations, Ayedun says, adding that Hoa has been granted a special status from the Brazilian Ministry of Culture, meaning that it can avail of a longstanding scheme that allows corporations to pay part of their taxes by funding cultural institutions and projects. In addition, Ayedun is working to develop a network of non-white patrons interested in racial justice that can also support the programme.

There is much work to be done. As Ayedun points out, since Hoa has shifted away from a commercial model, no other Black-owned gallery has opened in Sao Paulo. This means that, once again, the careers of most of Brazil’s non-white artists are “in the hands of white gallerists”.