In the history of both painting and the culinary arts, late 19th-century France remains an unrivalled moment. This is when Claude Monet’s masterful gaze settled on lilies and haystacks, and Georges Seurat’s on picnicking flâneurs; when the politician Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin published his groundbreaking The Physiology of Taste (1825) and the chef Auguste Escoffier ushered in his kitchen brigades.

It was also a time of political unrest and social change. With the Paris Commune of 1870, civil insurgency beset the capital while, in the countryside, the rural working class emerged as a force to be reckoned with.

These layered events underpin the Frist Art Museum’s group exhibition Farm to Table: Art, Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism. “Anything having to do with food is going to be interesting to everybody,” says Mark Scala, the Frist’s chief curator. “We’re always trying to find those common denominators, those links that tell deeper stories.”

Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Field of Banana Trees (1881) © RMN (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

The show is a package deal, jointly organised by the American Federation of Arts and the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, where it was first installed, with support from institutions including the Julia Child Foundation. Around 50 works will span the three decades between the 1870 Prussian siege of Paris and subsequent famine, and the turn of the century. Throughout, how food is produced, bought and prepared serves as that keenest of lenses with which to see what is troubling the nation: its economic woes, its social divides and its geopolitical entanglements.

Quite who works to feed people, and who stands to gain, is a recurring theme in pastures (Camille Pissarro, Jean-François Millet), vegetable gardens (Alfred Sisley, Paul Gauguin) and buoyant markets (Léon Lhermitte, Victor Gabriel Gilbert). The effusive greenery of Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Field of Banana Trees (1881) belies the exploitative colonial forces at work in what is a French Algerian plantation of foreign fruit.

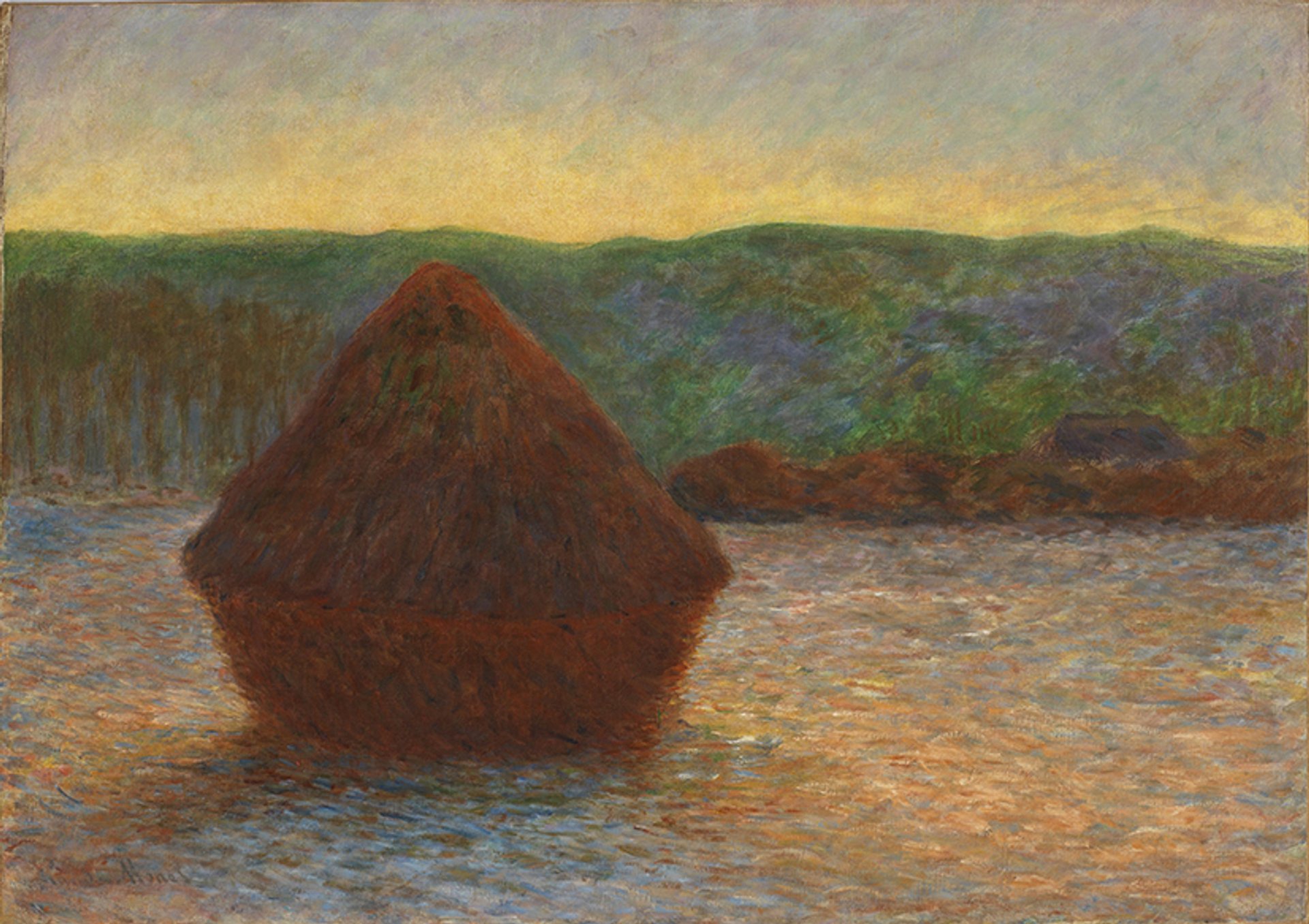

Claude Monet’s The Haystack (1891) depicted French farming in a different light

Courtesy Frist Art Museum

A superlative Monet Haystack (1891), meanwhile, is juxtaposed with a scene of a peasant woman actually stacking hay (1884), by Julien Dupré. Opulence and poor-man’s produce, hungry orphans and behatted diners—as Scala puts it, this is a feast of a show: “It’s really going to be beautiful and provocative.”

• Farm to Table: Art, Food and Identity in the Age of Impressionism, Frist Art Museum, Nashville, 31 January-4 May