“You never stifle an individual’s ability to be able to try to make a difference,” the artist Gary Tyler says. Of all the difficult truths he learned while incarcerated from the age of 16 for a crime he did not commit, this might be the most ingrained. And it has shaped much of his work since he was finally able to secure his release in 2016, after spending 41 years in prison.

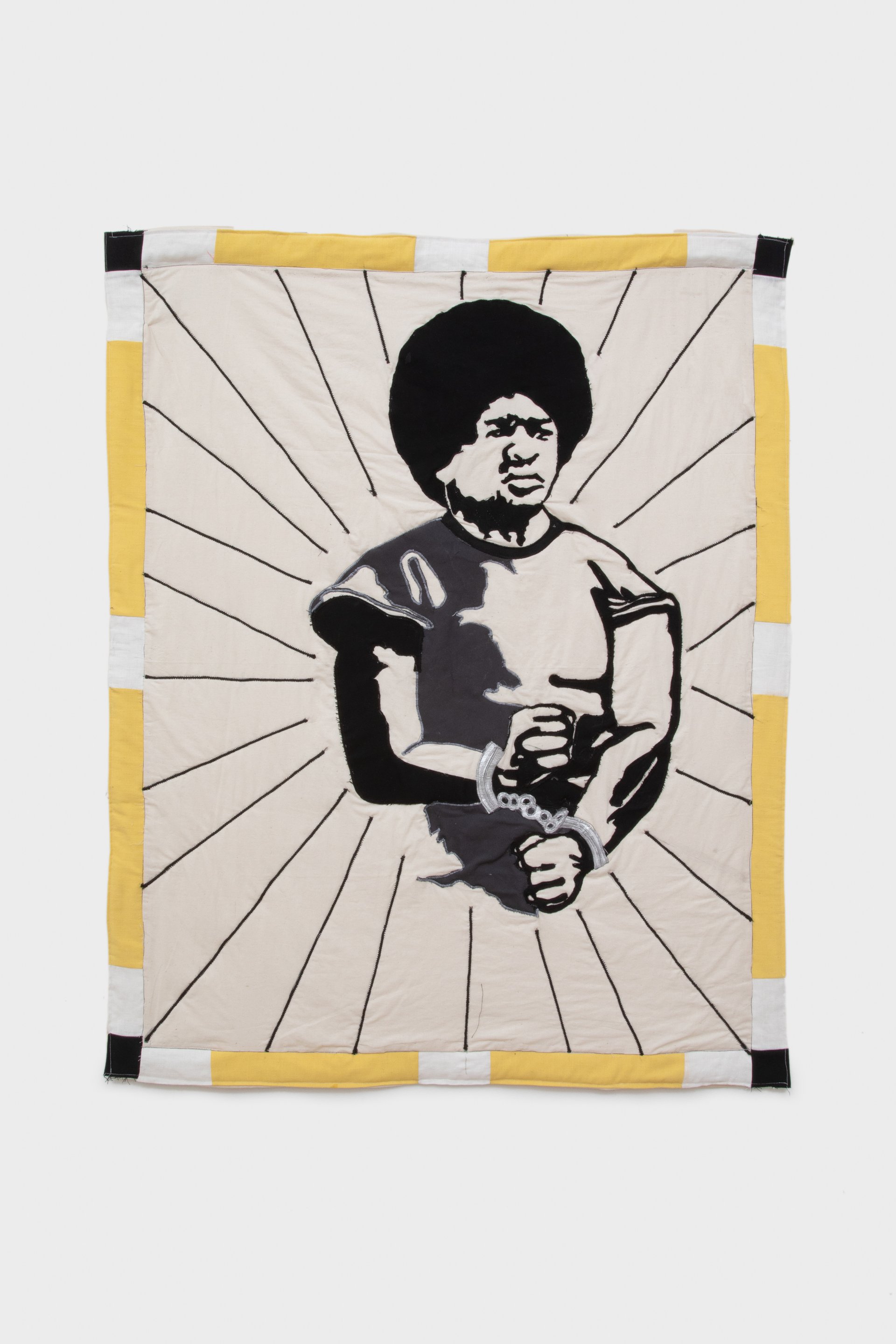

The quilts he is showing this month as part of the arts and culture programme at the World Economic Forum’s annual meeting in Davos, Switzerland, are in fact symbols of perseverance and potential. Two of them feature appliquéd self-portraits of Tyler. Defiant, 1976 (2023) is based on a photo taken in 1976, when he was 17 years old. At that point in his life, Tyler had already experienced more injustice than a teenager ever should.

Two years earlier, he had been on a school bus with other Black students in Louisiana, which was attacked by a mob of hundreds of white people angry about desegregation. During the clash, a shot rang out and a 13-year-old white boy in the crowd was fatally wounded. The bus was searched, and when Tyler complained that the police were harassing the Black students, he was arrested and beaten. He was later charged with first-degree murder for the boy’s death, was tried as an adult, convicted by an all-white jury and sentenced to the electric chair.

Throughout his detainment and trial, Tyler maintained his innocence, and the evidence used against him was questionable, including a .45 gun “found” by the police inside a bus seat, after the initial search failed to turn up a murder weapon. The image of Tyler depicted in Defiant shows him cuffed but unbowed.

Defiant, 1976 (2023), one of the three works by Gary Tyler that will be on display in Davos this month, references Tyler’s wrongful conviction for murder

The artist and Library Street Collective

Showing this work in Davos offers Tyler the opportunity to speak up for other incarcerated men and women in the US, “what you would call the silent voices that people really don’t hear”, he says. “It takes someone to advocate about their plight and what’s really going on. I know that America prides itself on its criminal justice system. But they tend to ignore the inhumanities within it and how their very citizens fall victim to it.”

When he was imprisoned, Tyler had the support of his family, especially his mother, who encouraged him to never give up, and his case was taken up by human rights leaders and organisations, including Rosa Parks and Amnesty International, which continually petitioned to have him released. “I just want to be a part of that light that tends to expose the degradation of those that’s incarcerated. To serve as a living example.”

Community leader

Being of service to his community is another lesson Tyler took to heart from his experience. During his time in the infamous Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as “Angola” after the former slave plantation it was built on, Tyler became a community leader, serving as a representative for the dormitory units and the president of the drama programme. He also worked in the prison’s hospice, taking care of fellow inmates at the end of their lives.

“It gives you a profound appreciation of life,” Tyler says of his work with hospice patients. “And it’s also life altering, because no death is the same, especially when you sit there and you take care of a person; you really get to know intimately the individual. I made it a mission that whenever I was assigned to take care of a patient, I would be there from the beginning to the end because that’s what I signed up for: to give back and let the individual know that they haven’t been forgotten.”

He also learned to quilt while working in the hospice. “Initially, I ran away from it because I was doing other things and I’m in this male-dominated environment,” Tyler says, explaining that he was worried about being thought of as taking on a “feminine” occupation in prison. But he soon understood that creating an object that provided such comfort was a noble cause, since it was part of “taking care of those that are terminally ill to give them the very necessities that they weren’t even afforded when they were well.”

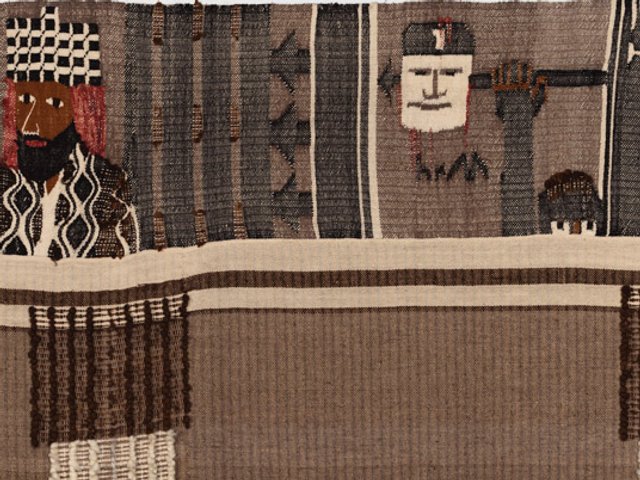

Rebirth (2023) will also be on display in Davos and features Tyler's recurrent butterfly motif

The artist and Library Street Collective

Learning to cut material and operate a sewing machine also brought up childhood memories for Tyler. “I remember my grandmother sitting behind one of the old Sears sewing machines with a foot pedal, and making blankets for the family,” he says. “And I remember as a kid laying up under those blankets. They were so heavy because of what she used as a batting: newspaper, old clothing scraps, moss that comes off trees, stuff like that. And that kept you warm at night when it was cold.” He also recalled his mother getting patterns from Sears and JCPenney catalogues to sew clothes for the family. “That was my connection,” Tyler says of his realisation that he came from a lineage of textile artists. “That was part of my DNA.”

It wasn’t until he was a free man, however, that he started thinking of himself as an artist. “In prison, doing any kind of craft like that, we called ourselves hobby crafters. And I thought I was just doing hobby craft work—not knowing that this is artistic work that people do,” he says. “I didn’t start embracing the idea that I was an artist until a few years ago.”

Tyler has in turn been widely accepted by the art world. He had his first solo gallery show at Detroit’s Library Street Collective in 2023, and his work has been shown at the Armory, Untitled Miami Beach and Frieze Los Angeles art fairs, at the last of which he was awarded the 2024 Impact Prize. He also received an honorary degree from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, and one of his quilts hangs in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC.

Endurance and optimism

Joseph Fowler, the head of arts and culture for the World Economic Forum, says inviting Tyler to show in Davos “is not just a recognition of his art, but also an acknowledgment of the larger message his work conveys: that even in the darkest of circumstances, there is the potential for growth, transformation and a greater sense of connection. Gary’s art is a living symbol of his resilience, a vehicle through which he channels his experiences and offers hope to others. His artistic practice stands as proof that art can heal wounds, spark social change, and reframe narratives about race, justice and human rights.”

For Tyler, showing at Davos allows him to bring his work to an international stage and reach a wider audience. “I would have to be out of my complete mind not to take advantage of an opportunity like this,” Tyler says, “especially when you would have the attention of people from around the world.” And the message he hopes viewers will take from his work is one of endurance and optimism. “I just want people to know that my work exemplifies my life, what I went through, and I was able to survive it. And despite it all, I feel that itself kept me psychologically intact,” he says. “I know that being bitter is not the answer.”

This sense of hope is embodied in another quilt at Davos, Rebirth (2023), featuring a vibrant butterfly in flight, a regular motif in Tyler’s work. This can also be seen as a self-portrait or a portrait of any incarcerated person seeking to transform their circumstances. “Others who’re going through the same transition are making the best out of their unfortunate situations, to become better people. Because those in prison, they’re still human beings, no matter what they go to prison for. And society should never throw people like that away, because those individuals still have potential,” he says. “We want to flourish and be able to give back to society, just like the butterfly.”