Buyers can be picky. A painting in a gallery may be too large, or not large enough; the subject matter may be OK, but could there be more blue? Many dealers and advisers field these types of requests regularly, and arrange private commissions of art to suit particular preferences.

“I arrange so many private commissions,” says Mary Sabbatino, the vice-president and partner at New York’s Galerie Lelong—“so many” meaning several every year. Among the artists in her gallery who have been asked and agreed to create a piece for a particular buyer are Leonardo Drew, Andy Goldsworthy, Jaume Plensa and Kate Shepherd. The discussion with a client, she says, often begins with “I really love the artist’s work” and moves on to how that person can get a piece that suits their needs. The conversation moves to the scale of the work, the materials to be used and even the palette.

At times, the prospective buyer will be taken to the artist’s studio to meet the artist and see more works. Laura Solomon, a Manhattan adviser, says that back in 2021 a client of hers had expressed interest in the multi-media work of New York artist Jacob Hashimoto. The client had never seen the artist’s work in a gallery but only in photographs in art magazines, “so I set up a studio visit”, she says. At the time, Hashimoto was preparing for three upcoming gallery exhibitions, so the studio was filled with unseen and unsold artworks, “but nothing was at the right scale for this client, so a commission was arranged”. Solomon says the artist had done private commissions previously, “so he was comfortable with the process and the timeline”. In fact, the artist’s studio assistants already had contractual agreements for commissions that simply needed to be filled out and signed. The commissioned work could not be started until the gallery shows were over, which meant a wait of several months, but there was no problem with that. After that initial meeting in the studio, there was no direct communication between the artist and the client. “Everything went through me,” Solomon says.

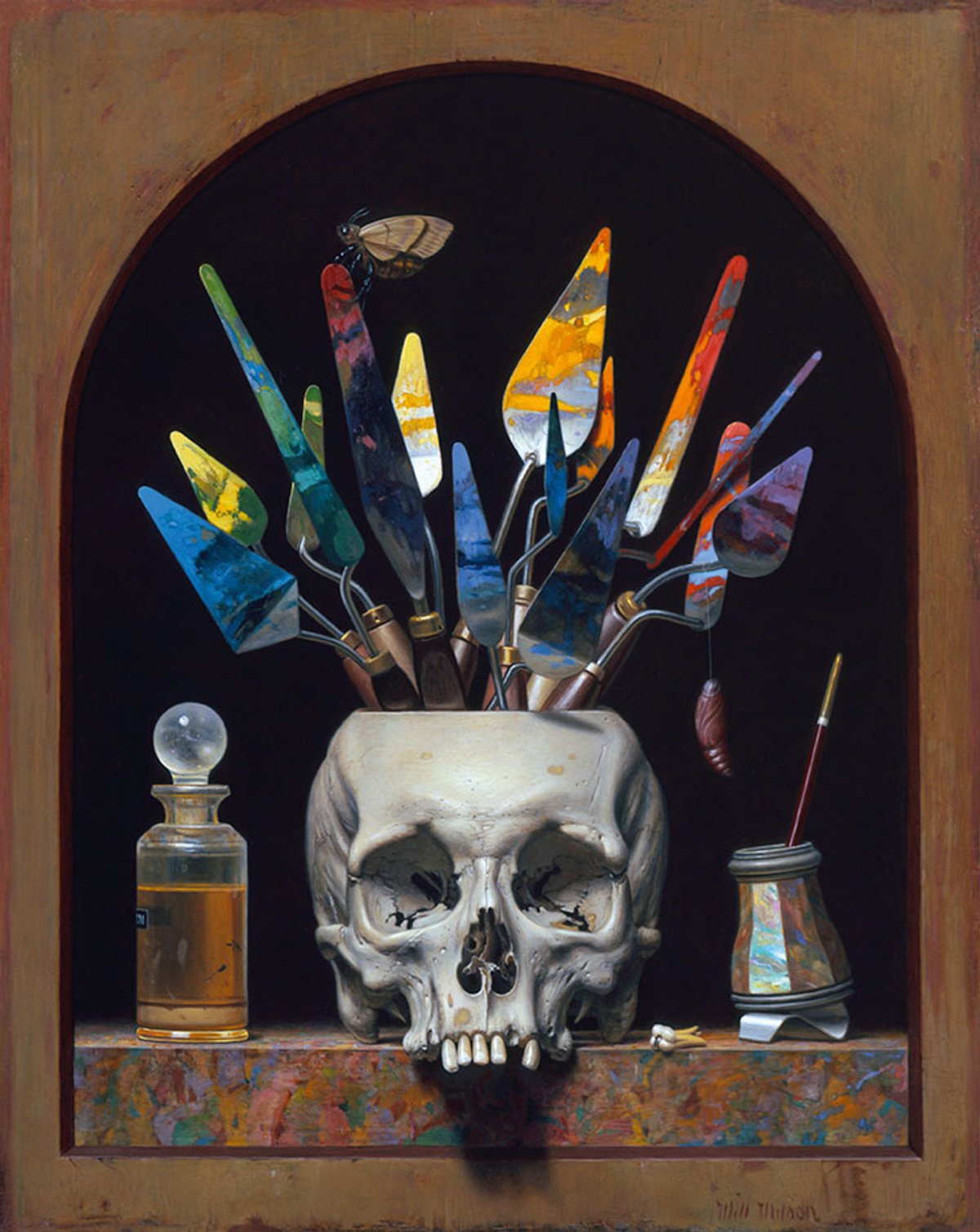

Taking direction suits some artists more than others. Painters Will Wilson—who lives in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico—and New Yorker Tom Christopher both have backgrounds in commercial illustration before turning to fine art full time. “I’m given criteria that I’m supposed to work with, like match the colour of the couch,” Wilson says, “but if the subject is interesting enough for me to do it, I will.” He notes one particular painting he had shown in a gallery, a still-life of a palette knife with some paint colours on it, that brought him requests for that same image from 16 collectors. “So, I made 16 more paintings of it for 16 different people, with the colours on the palette knife a little different in each one.” Christopher states that he likes working directly with private clients—“galleries get in the way of things”, he says—and tries to make them happy with the final product. “Artists always say they don’t do that, but they all do.”

Will Wilson © the artist

The New York painter April Gornik notes a certain reluctance to take on a private commission. “I completely understand people wanting something custom-made for them, but it’s a whole other kind of overlay in my studio process to try to both work in my head and with what I imagine to be their expectations,” she says. “My brain doesn’t have the bandwidth for much of that.” Still, with all those caveats, she does from time to time produce something for a buyer—usually “a friend who’s also a collector”—if the subject is inspiring to her and she will be “happy with what I’ve made in case the collector rejects it”.

Rejection isn’t something that gallery artists usually have to think about. A buyer who sees an artist’s work in a gallery exhibition may choose not to buy it, but that does not count as a rejection.

One way that the New York artist Maureen O’Leary limits the number of offers for private commissions is by pricing them higher than for her already-created pieces, “as much as double regular prices”, she says.

The pricing of a commissioned work is not as straightforward as one that has already been produced and is being displayed in a gallery. The gallery gets its commission, although that may be split with an adviser when that person is involved.

Drawing up a contract is part of the process, usually setting up a timetable for completion of the work and for payment to the artist. That may be a third (or half) upfront, perhaps another third at a midpoint approval stage and the remainder after the piece has been completed and accepted by the buyer. Part of what stretches out the time in a commissioned work is the mediated communication between artist and buyer, as well as the approval process. Sabbatino says that some clients will travel to Spain, where Plensa lives and works, for example, to see the work in progress, while others will look at photographs sent to the gallery.

Commissioning a work takes longer and may cost more than acquiring a piece that already exists, but, for many buyers, the bragging rights are far greater and worth the price.