Uncertainty and instability are intrinsic to human life—but so is our instinct to block them out with our minute, private gestures of continuity. That denial allows survival, and simple survival is the most indelible kind of optimism. Everyday Practices (until 20 July), a collection show at the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), uses the performances of the Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh as a starting point for exploring how artists express defiance through mundane actions.

“Hsieh’s radical engagement with time through his durational performances resonated deeply as a larger framework for understanding resilience in challenging contexts,” says Teng Yen Hui, curator and manager of collections at SAM. Hsieh’s projects, which started when he confined himself to a cell in his apartment for an entire year, find reflection in the exhibition’s “focus on the profound meaning embedded in the mundane, particularly as a response to adversity or systemic struggles”.

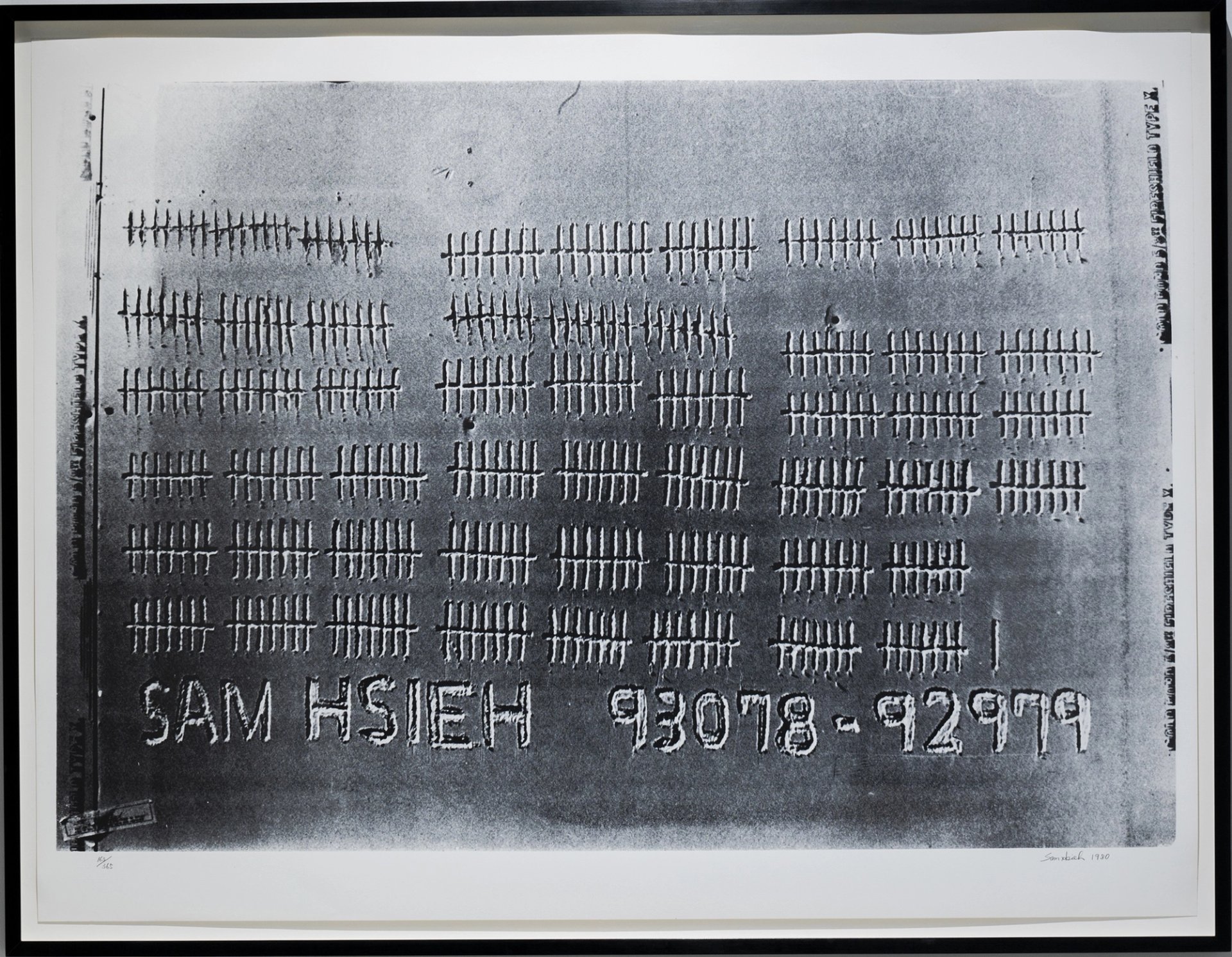

Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance (1978–1979) was made when the artist confined himself to a cell in his apartment for an entire year Courtesy of Singapore Art Museum

The works by 19 artists and one collective in Everyday Practices includes Hsieh’s One Year Performance (1978-79), presented via documentation, and A Suite of Dark Drawings (2015), body portraits drawn by Malaysia’s Tengku Sabri Tengku Ibrahim after a stroke left him half paralysed.

Many works explore socio-political issues, such as Soap Blocked (2016), in which the artist Htein Lin meticulously arranges hundreds of small carved soaps in the shape of a map of his native Myanmar. “Each block’s tiny, encased figure symbolises his personal history of imprisonment for political opposition, and also the collective struggles that citizens of Myanmar face under political oppression,” says Teng. The artist was a political prisoner from 1998 to 2004 and again in 2022, and the soap he carved while incarcerated “becomes a poignant metaphor for resilience against dehumanising forces”.

The residual traumas of the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia echo in Svay Sareth’s video Mon Boulet (2011), for which the artist spent six days dragging an 80kg metal ball the 250km from Siem Reap to Phnom Penh. Other works, such as the Thai artist Imhathai Suwatthanasilp’s The Flower Field (2012), “present a more intimate narrative of loss and grief”. The thousands of “flowers” on a bed-sized light box, handwoven from hair provided by cancer patients, pay tribute to the artist’s father, who passed away from cancer. “The work evokes a utopian realm of rest and of hope.”

Sub-themes of “everyday”, “repetition” and “endurance” guided the selection. The first, says Teng, “considers everyday objects, spaces, familiar environments and lived experiences”. Repetition explores how art-making can be an “act of repeating an action, gesture, or even motif” to convey meaning and mark time. Endurance involves overcoming the challenges of physical constraints, from a political prison, the prison of an ageing human body, or of a deteriorating planet.

Everyday Practices debuts a new collections gallery at SAM’s premises at Tanjong Pagar Distripark. Teng says the show reflects the commitment of the museum, established in 1996, to build “a distinct and diverse collection of contemporary art featuring significant works from Singapore, Southeast Asia and beyond”, showing 18 artists from Southeast Asia and two from East Asia. Along with Hsieh, the latter includes the mainland Chinese artist Sun Xun, whose interplays of mythology and history help to transcend geography and provide a broader context. “On a deeper level, it also hopes to inspire humane futures by creating platforms [to cultivate] understanding and empathy of each other’s lived experiences,” says Teng.

Turbulence of Southeast Asian history

The turbulence and tragedy of recent Southeast Asian political history reverberate in the exhibition: colonisation, war, dictatorships, genocide, revolution, more war—and among them determination and hope, like a carved bar of soap smuggled out of a prison. Teng says the show was curated in consideration of varying levels of historical knowledge. Some viewers may feel particular poignancy and resonance in works dealing with “ongoing issues like authoritarianism, economic disparity and cultural shifts”. For those less familiar, the exhibition provides an entryway to the histories through the art’s “universal themes—resilience, grief, community— that transcend specific historical contexts.”

The works highlight the power of individuals, and the collective impact of their resilienceTeng Yen Hui, Singapore Art Museum

Those histories through artists’ eyes also provide a lesson in human fortitude, recalling the Audre Lorde poem Litany for Survival, which concludes: “So it is better to speak | remembering | we were never meant to survive.” Everyday Practices presents the many ways that Southeast Asia’s artists have eked out survival. The show’s works, says Teng, “highlight the power of individuals and the collective impact of their resilience. Art can serve as a means of navigating adversity, fostering empathy and understanding, and uncovering strength in times of struggle.”

• Everyday Practices, Singapore Art Museum, until 20 July