The reduction of inheritance tax relief for UK businesses, announced by the government in October, could have a big impact on artist estates as well as family firms, experts say.

The change sees 20% inheritance tax (IHT) applied to business assets worth over £1m, previously entirely exempt from IHT. It is among a number of tax rises outlined in the new Labour government’s autumn budget, tasked with finding £40bn for public finances, which have concerned the UK’s art and antiques industry.

The budget also hikes taxes on “non-doms”—UK residents who have their permanent home outside the UK—and offshore trusts, a move started by the Conservative party, which has already prompted wealthy collectors to move to countries with more lenient fiscal regimes such as the UAE and Italy.

Employment within the art industry could also be impacted by the rises in employer national insurance contributions (NICs) and the minimum wage, alongside a crackdown on zero-hours contracts, which some businesses say will reduce their hiring potential. However, capital gains tax (CGT), which was expected to rise in line with income tax, only went up from 20% to 24% (for the higher rate), an increase that is unlikely to deter people from selling their art or antiques.

‘Cultural own goal’

Rudy Capildeo, the joint head of the art and luxury group at the London law firm Wedlake Bell, describes the reduction of business property relief (BPR) as a “cultural own goal” due to its potential impact on artist estates.

“Artists tend to be asset rich and cash poor, and often their best prices are achieved towards the end of their lives [which will raise the IHT valuation of the works they leave behind],” Capildeo says. “So, they look at their studio and think: I’ve got all this stock and, if you base it on my last few sales, it will run into the many millions.”

Wedlake Bell was the legal adviser to the now dissolved artist estate charity Art360, which worked with 54 UK-based estates and artists, including Alison Wilding and Monster Chetwynd. Capildeo and his colleagues encouraged these artists to make use of BPR to avoid the standard 40% inheritance tax on their estate.

In order to qualify for BPR, an artist must be seen to be running their business in the two years prior to their death—which could mean they are still painting, have had an exhibition, or their works have been sold at auction. “An artist can say that their studio, plus all their work and tools of the trade, should sit outside their personal estate and within the business, which previously meant artists’ families did not have to do a fire sale of their work to pay inheritance tax,” Capildeo says.

But now, Capildeo thinks many artist estates will be forced into such fire sales in order to pay up the 20% IHT over £1m. “HMRC don’t think about what you might actually be able to achieve for the art. In the US, the IRS [Internal Revenue Service] can depress the valuation of an artist’s estate because they take into account the fact that, if all that work came onto the market at the same time, it would sell for less.”

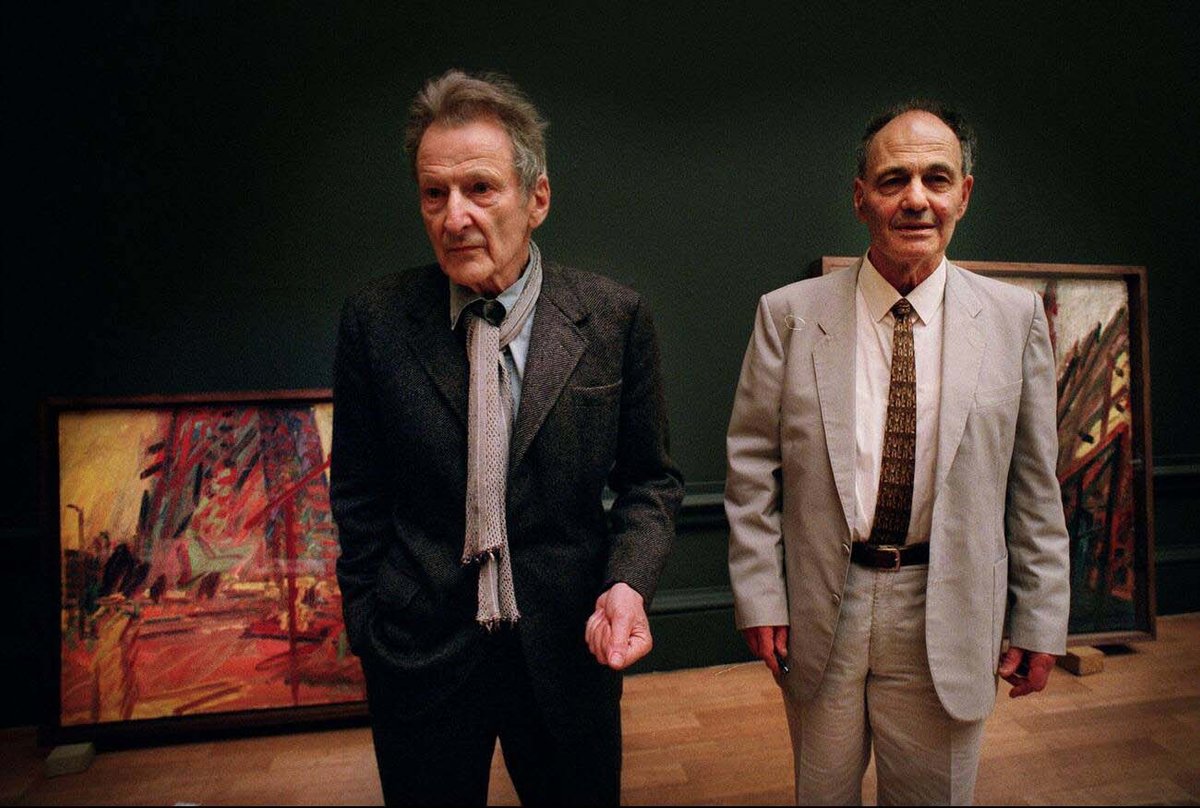

“We’re living in this very fortunate time of great British artists—such as the YBAs and Frank Auerbach, who has just died—but their descendants will be left with little choice but to sell works,” Capildeo says. “And, when you’re pushed into it, you often don’t get the best price.”

Family-owned art and antiques businesses that have over £1m in stock and other property will pay the extra 20% IHT, too. Mark Dodgson, the secretary general of The British Antiques Dealers’ Association, says one member told him that the new measures “would certainly prevent their ability to take over the business on their father’s death, since they simply do not have the cash to be able to pay the inheritance tax”. Another member said their hope “had always been to keep their well-known and highly respected antiques business sustainable for future generations and are disappointed that the government has chosen to hit hard-working families who have reinvested into their small businesses with a view to keeping them going in the longer term”.

Capildeo foresees an increased use of art financing to quickly extract cash due to the catch 22 of IHT: nothing can be sold from an estate until a grant of probate has been issued, and that will not be issued until some of the tax has been paid. Added to that, IHT must be paid within six months of a death or interest will start to run, currently at 7.25%.

Wendy Philips, the former head of tax and heritage at Sotheby’s who joined the specialist cultural property advisory Tennant McQuillan in October, also thinks the BPR changes will lead to more works coming to market from artist estates.

Philips foresees more works being put forward for the Acceptance in Lieu scheme, which (jointly with the Cultural Gifts Scheme) has an annual budget of £40m of tax foregone, so she and Capildeo predict a rush of applications in January. The scheme is “the single most important way of getting works of art into museums, especially now budgets are so tight”, Philips says, pointing to the notable example of Lucian Freud’s collection of 40 paintings and drawings by his friend Frank Auerbach which were accepted in lieu of around £16m in inheritance tax following Freud’s death in 2011, using some of the following year’s allowance. (Auerbach’s own estate will likely be impacted by the changes to BPR.)

A question of importance

Philips predicts an increased use of conditional exemption, too, in the case of “pre-eminent” art and chattels considered to be of national importance. This mechanism, untouched by the latest budget, comes with strict conditions: in order to claim, you must give public access to the object for at least 28 days a year (through your house being open to the public, or through long-term loan to a museum).

“With the huge reduction in BPR, there is likely to be an uptick in claims for conditional exemption, because it’s the one relief they have not touched,” Philips says. Big country houses often use “a menu of reliefs”—BPR, agricultural property relief (subject to the same reform as BPR, so IHT is now due on farms) and conditional exemption—so works of art may well be sold to pay tax on farmland, for example.

Location, location, location

The scrapping of non-domicile status from the tax system from April 2025, part of non-dom reforms that the chancellor Rachel Reeves says will raise £12.7bn in taxes over the next five years, has already prompted many wealthy individuals to leave the UK to reduce their tax liability.

This is a very big change that will affect many internationally mobile people

“Under the new rules, any individual who has been tax resident in the UK for ten of the previous 20 tax years will be taxed in the same way as permanent residents of the UK, regardless of their nationality,” says Will Cudmore, a senior associate in the private client team at Farrer & Co. “This means UK IHT at 40% on all their worldwide assets. Any trusts settled by that individual, including non-UK trusts, will be brought within the scope of UK IHT, too, meaning ten-year anniversary IHT charges and IHT charges on capital leaving the trust at up to 6%. This could particularly affect non-UK trusts owning art, and their tax status will now be pinned to the tax status of the settlor.” And in the case of a “dry” trust, containing only art, for example, some of that art may have to be sold in order to pay the ten-year tax. Until now, an existing offshore trust could stay out of the UK inheritance tax net, so, Cudmore says, this “is a very big change, and one that will affect many internationally mobile people”.

Chancellor Rachel Reeves wants to raise £40bn for public spending

Crown copyright; Licensed under the Open Government Licence

Camilla Wallace, a senior partner at Wedlake Bell, says that the tax increase on carried interest is also having an effect, as “the private equity community saw this coming and, in quite high numbers, have relocated to places like Dubai and Italy. So, it follows that they will be buying less art in London.” Carried interest, the profit share paid to fund managers, had been taxed to CGT at 28% but, in 2026, will come within the income tax framework, initially at 34% (including NICs) but with scope for mission creep up to 45%.

Salaries rise, hiring drops

Meanwhile, rising wages and red tape is concerning art businesses. The Employment Rights Bill, introduced in November, cracks down on zero-hours contracts, giving staff full employment rights from day one. From April 2025, employers will also have to pay an increased NIC (from 13.8% to 15%) on salaries over £5,000 (previously £9,100), with the minimum wage rising 6.7% to £12.21 per hour for over-21s.

Guy Schooling, the chairman of Sworders Fine Art Auctioneers in Essex—which has around 60 full-time employees and 20 to 30 occasional staff—says the changes represent a “triple whammy” that will cost the firm “tens of thousands of pounds a year”. The rise in minimum wage, he says, will have a knock-on effect as employees are asking for salary rises in line with it, while many of the auction house’s weekend viewing staff are on zero-hours contracts

“We don’t want to say we can’t give staff a pay rise this year because of these extra costs; that’s not fair,” he says. “We want to keep hold of our brilliant staff, but we’re having to think very carefully about how we function as a business going forward.” The firm, Schooling says, will not be making people redundant, but it has paused hiring.

On a more positive note, Dodgson points out that some businesses with only a few staff could be better off thanks to an increase in employment allowance—allowing a business to claim back NIC payments—which have gone up from £5,000 to £10,500 per year. However, he says, “Members with 15 or 20 employees will be paying more.”