Francis Picabia's final years and legacy, which cemented the maverick painter's place in art history, are the focus of an exhibition opening in Paris next week.

Francis Picabia: Eternal Beginning at Hauser & Wirth (18 January-16 March) is the first exhibition to look specifically at the final decade of the artist's life, with 46 paintings created between his return to Paris at the end of the Second World War to his death in 1953. During that period Picabia, a restless artist who frequently changed direction and explored many different genres in his painting —Jean Arp called him “a Christopher Columbus of art”—abandoned the figurative nude works that had characterised his wartime output. He returned to abstractionism—albeit, says Arnauld Pierre, his biographer and co-curator of the show, incorporating elements of figuration and taking inspiration from prehistoric sources he had not employed in the past.

Change of mood

“With this exhibition we will show this period as a specific moment in Picabia’s career, totally different from what he had done before,” says Pierre, who is also the author of Francis Picabia: Painting without Aura (2002). “There was a great change in his mood, in his way of painting, in his style.” In a lifetime of complex, diverse works, Pierre says, this exhibition will show his final years were every bit as fascinating and relevant as what had gone before.

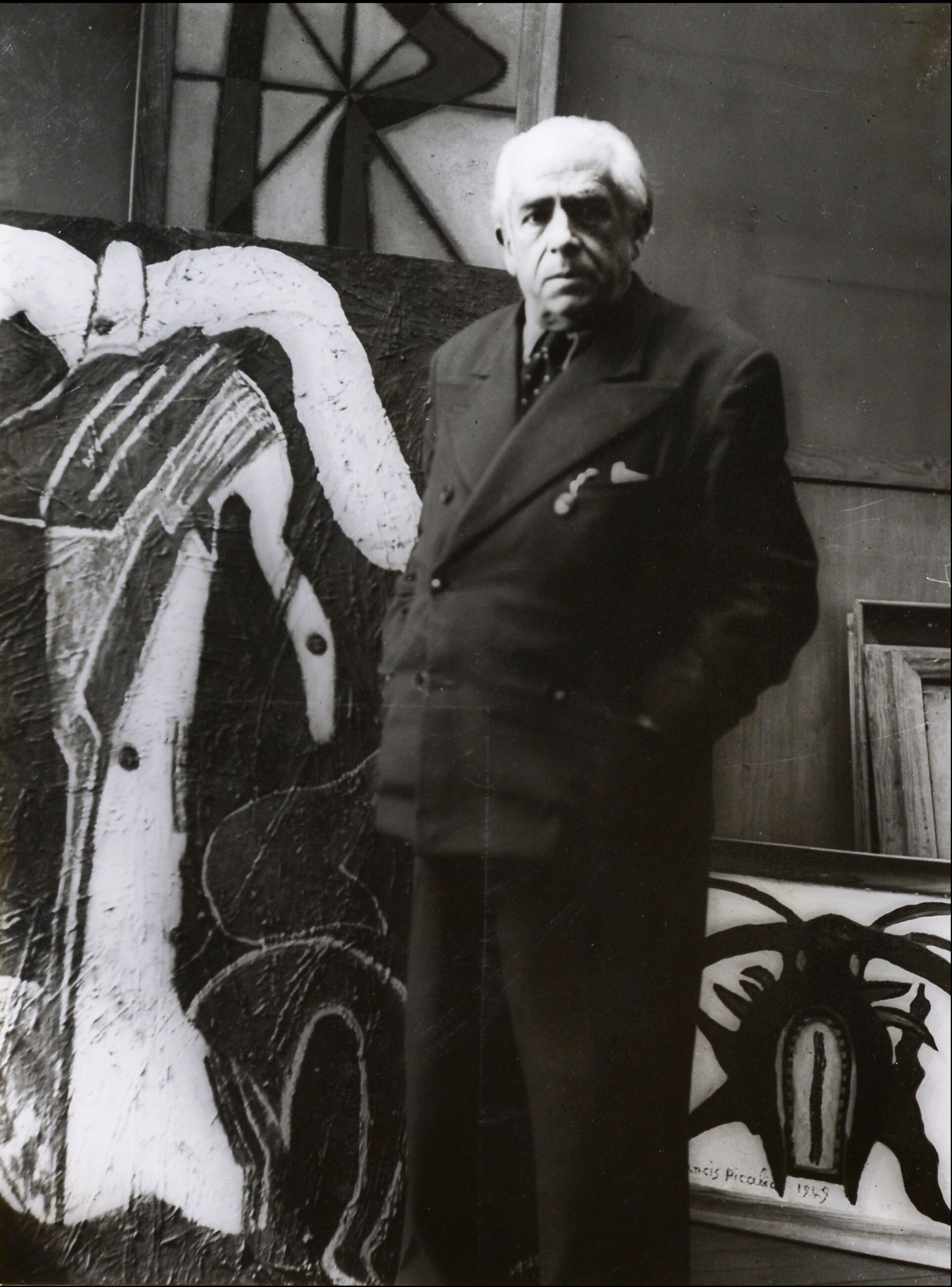

Picabia in his studio at 26 rue Danielle-Casanova (formerly rue des Petits-Champs), Paris (around 1948–49) Image: Archives Comité Picabia, Paris

Pierre's co-curator, Beverly Calté, knew Picabia’s widow Olga in the 1980s and 1990s, and worked with her and with Pierre on the artist’s archive, the Comité Picabia, which published his catalogue raisonné. “In his late years Picabia used some of his sorrows and his anxiety from earlier times to create a new body of work. He was older and life was complicated. And he surrounded himself with younger artists for whom he would be a terrific inspiration,” she says. These included Pierre Soulages and Jean Michel Atlan, who saw him as a still-vital and exciting artist.

Bridge to a new era

Picabia, born in Paris in 1879, was closely involved with Dadaism and experimented across his career with styles from Impressionism, Pointillism and Cubism to Surrealism and abstractionism. “He was a melancholic man whose psyche was closely associated with events in the wider world, especially during the two World Wars," Pierre says. The heaviness of the world is reflected in his post-1945 works, when he knew his own end was not far away; and yet he managed to refresh his oeuvre, and also provided a bridge between pre-war artistic Paris and the new era that followed the departure from France to the US of so many of his contemporaries.

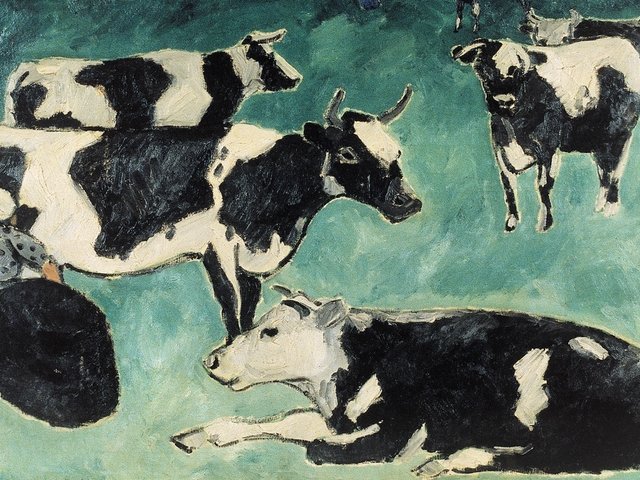

Francis Picabia, Villejuif (1951) Photo: Stefan Altenburger Photography Zürich

The exhibition, which moves to Hauser & Wirth’s New York gallery on 22nd Street in May, includes Villejuif (1951), which was for many years thought to have been his last work. But that is now believed to have been Points, dated 1952, also in the show. And, Pierre says, there may even have been other pieces created in his final months in his Paris atelier, where he was bedridden for many months before dying in November 1953.

• Francis Picabia: Eternal Beginning, Hauser & Wirth, Paris, 18 January-16 March