In a Gaza battered by war and deprivation, Israel’s severe restrictions on aid and commercial goods have intensified a humanitarian crisis that the UN described in a 12 November briefing as “catastrophic”, warning of “imminent famine”. Yet, against all odds, Gaza’s artists continue to create. Facing shortages of basic supplies, from food to paper, they turn whatever they can find into tools of expression to document the relentless conflict around them. The Art Newspaper spoke with four artists who, amid the rubble and chaos, are using their art to preserve a record of life in Gaza and to share their stories with the world by any means possible.

Khaled Hossein

Hossein, a sculptor from Rafah in southern Gaza, initially stayed in his hometown when the war began. Israel had designated it a safe zone and directed much of Gaza’s population there. Hossein (pictured above) worked tirelessly to provide for his family and ensure their safety, leaving little time for art.

But when Israel’s military campaign reached Rafah in May 2024, he and his family were forced to flee, and their home was destroyed. In Deir al-Balah, surrounded by old friends from Gaza’s once-vibrant art scene, he was encouraged to start creating again.

Having lost most of his old life, Hossein fashioned his own tools and began making sculptures from everyday clay, often inspired by the death and loss surrounding him. “There are many cases of loss, you can’t imagine. Unfortunately, we can only express this,” he says.

Hossein places his sculptures in various environments, such as devastated homes, photographs them and then destroys them, filming the entire process. Due to a lack of space and the constant threat of displacement, he does not keep his works.

One piece, titled Yousef, is inspired by a heartbreaking event: a mother searching for her son in a hospital and describing her “beautiful boy” to staff, only to be taken to his lifeless body. Yousef’s mother’s words deeply moved Hossein, prompting him to recreate her son in sculpture “to express the extent of the loss”.

Other works include Martyr’s Farewell Kiss, depicting a woman affectionately kissing a dead man, and a sculpture of two dead toddlers lying side by side, one with only a head and the other missing a limb. He placed this piece amongst the ruins of a house and photographed it.

The clay creates a strange state of coexistence with the place, as if I don’t see, hear or speakKhaled Hossein

“This is a scene we see a lot after houses are bombed—children’s bodies scattered from the explosion,” he says.

Hossein says that when he holds clay, he loses track of time, finding peace amid the chaos of a warzone. “The clay creates a strange state of coexistence with the place, as if I don’t see, hear or speak,” he says.

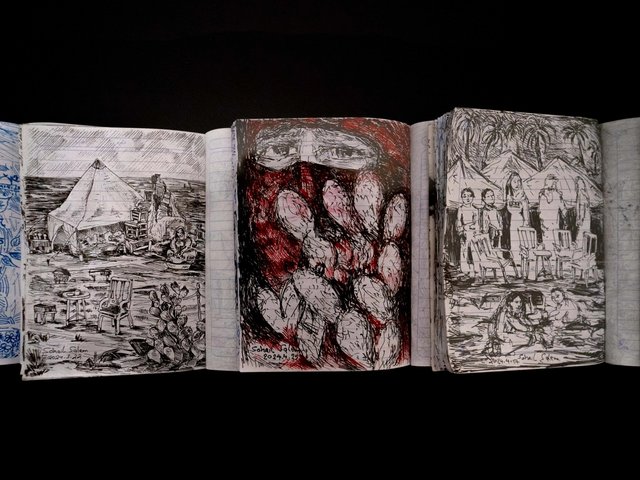

Artist Raed Issa with children in his tent studio Courtesy of the artist

Raed Issa

Issa has transformed his temporary shelter into a space of teaching, creativity and solace he calls “my studio in the tent”. “I created it for some privacy, but every day there is no peace or comfort, there is just fatigue, anxiety, and fear,” says Issa, an artist and co-founder of Eltiqa Group for Contemporary Art, Gaza’s first contemporary art space, which was destroyed in December 2023.

Issa’s “beautiful home” and studio in Gaza City were also bombed by Israeli forces. The father of four has been displaced more than ten times and is now in Deir al-Balah in the centre of Gaza. “Everything turned to ashes and now I live in a tent that does not protect us from the cold of winter, the heat of summer. Or the roar or threat of airplanes,” he says.

Despite the hardships of life under constant bombardment in Gaza, Issa paints what he sees “almost every day”. He documents his surroundings in “a visual diary of suffering”, which he regularly shares on Facebook and Instagram. His themes include tragedy, fear, joy, fatigue and waiting. But with a severe shortage of art materials, Issa has had to get creative, repurposing discarded aid boxes and even medical envelopes as canvases.

The scarcity of paint has pushed him to use “anything” at hand as pigments, such as tea, hibiscus, coffee, charcoal and even rust. “In the beginning, I used alternative materials because there were no colours, but now I love them,” he says.

Issa, who has worked with children for more than 25 years, has opened his makeshift studio to displaced kids in the camps. He focuses on their “emotions and psychological exhaustion” while nurturing the talents of the more gifted. They have the freedom to express themselves however they wish. “Children are sincere in their feelings, which is why I love working with them,” he says.

Issa says the international arts community can support Gaza’s artists by exhibiting their work or acquiring their pieces, some of which are already being displayed abroad.

“This war is a long nightmare that has affected people, stones, trees, art, humanity and dignity. But we have not despaired or broken,” he says.

Muralist Ayman Al Hossary paints calligraphy on a destroyed building Courtesy of the artist

Ayman Al Hossary

Al Hossary was once a popular performance artist and muralist who brought colours to Gaza’s walls. When the war broke out, he was forced to flee his home in northern Gaza with his wife and 22-month-old baby, “hoping to return soon”. However, Al Hossary’s home and studio were destroyed by Israeli bombardments. He has been displaced at least nine times.

With no prospect of ever returning home, he began to gather whatever tools and paint he could find, using Gaza’s rubble as his canvas. His work provides a brief respite for both him and his audience amidst the chaos and the overcrowding. “I practise art to escape, even if just for a while, from the depression and hardships of war,” he says.

Al Hossary adorns tents and ruined buildings with calligraphy—poems or words recounted by those who have lost loved ones or their homes during the war. At times he paints sorrowful eyes on the rubble, an act he describes as “a witness to this destruction and a documentation of this difficult period in our history”.

“What motivates me most is people’s interaction with art,” he says. The positive reception he receives has inspired him to involve others in his creative activities, especially children, to lift their spirits. Even as his supplies run low, with his last paints almost exhausted, he is busy working towards a performance piece amid the rubble of destroyed homes.

Ahmed Muhanna, an artist and art therapist, works with children in displacement camps Courtesy of the artist

Ahmed Muhanna

Muhanna, an artist and a specialist in art therapy for children, saw his life “turn upside down” when the war began. For the first three months, the horrors of the conflict left him unable to even hold a pencil or brush. His studio, located in Deir al-Balah, overlooked a school that quickly became a shelter for displaced people, where he witnessed their suffering.

“I used to sit in the studio, watching people’s tired faces, torn by war, and scenes of children carrying water or queues for food,” Muhanna says. Eventually, he realised he had to compose himself and act, concluding that documenting what he was witnessing through art was the way forward.

Low on paper, Muhanna looked around his studio and noticed the abundance of aid boxes. He found them a fitting surface for his art, since these boxes had become an integral part of their lives during the war. The words “not for sale or exchange” stamped on the boxes added another artistic dimension to his work.

“I began documenting all the scenes I witnessed—whether with my own eyes, or through social media, or through stories I heard,” he says.

Muhanna continues his work with children, visiting camps three times a week, and encourages his three children to express their feelings through art. Despite his best efforts to shield his children from the violence, his youngest son Wissam often depicts themes of eviction and bombardments in his drawings. Muhanna was stunned when he found Wissam’s drawing of an Israeli attack on a school, including dead bodies. “I ask myself how a six-year-old child expresses himself this way,” he says.

But the shortage of paper and paint is making Muhanna’s efforts increasingly difficult. He hopes international aid agencies will begin to deliver the basic material and tools he needs to continue his work. “I desperately need tools. I am looking everywhere for supplies to keep working, drawing and helping children,” he says.