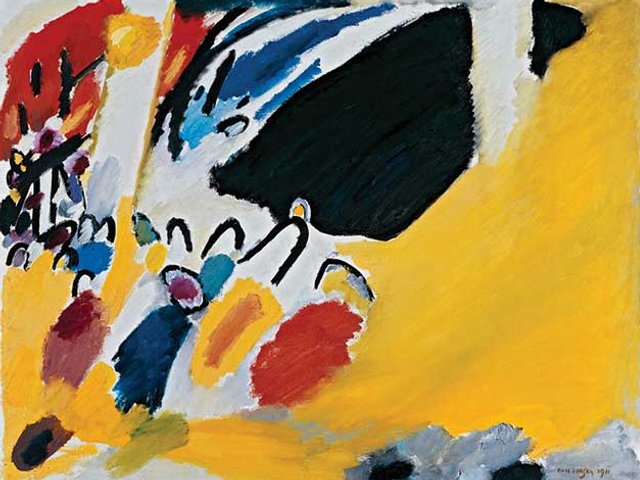

In the years leading up to the First World War, two mystical-minded Russian friends helped determine the course of German Expressionism. One—Wassily Kandinsky—is remembered as an influential visionary and pioneer of abstraction; the other, Alexej Jawlensky (1864-1941), is now just getting his due. In 2017, the Neue Galerie New York mounted the artist’s first major US survey, and this month the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, north of Copenhagen, will give him his first Scandinavian monographic show.

Alexej Jawlensky will feature 61 works, running from 1908, when the artist began to explore an ever-wilder palette, to his final, subdued works of the mid 1930s, when he was crippled by arthritis.

Kandinsky and Jawlensky were part of the Munich circle of artists now known as Der Blaue Reiter—a group that included Kandinsky’s companion Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc and August Macke. The artist Marianne Werefkin, a Russian aristocrat and Jawlensky’s companion, held a salon that often kept the group together.

In Germany, Jawlensky is still best known for the Munich period, which ended with the outbreak of the First World War, when Russian nationals Jawlensky, Werefkin and her maid (who was also the mother of Jawlensky’s child) fled to neutral Switzerland. But the Louisiana curator Mathias Ussing Seeberg is using the Expressionist years as a point of departure.

Jawlensky's Grosse Meditation: Glut (large meditation: glow, 1936) Photo: Museum Wiesbaden / Bernd Fickert

Cooped up near Geneva, Jawlensky began a series of repetitive works that gradually and then completely altered a view from his window. By the time of 1916’s Variation: Dämmerung (variation: twilight), trees and a road had become curvaceous blots of colour. “When he leaves Germany,” Seeberg says, “that’s when he gets really interesting.”

Jawlensky returned to Germany in the early 1920s, and settled down with his son’s mother, Hélène Nesnakomoff. While Kandinsky and another friend, Paul Klee, were putting in time in the Bauhaus in Dessau, Jawlensky was obsessively painting a single face in small works on paper.

In the mid-1920s paintings such as Abstrakter Kopf: Mysterium (abstract head: mystery, 1925), the colours remain multifarious and expressive. A decade later, when he typically had to hold a brush with both hands, the palette darkens and deepens: in Grosse Meditation: Glut (large meditation: glow, 1936), the face has become an infernal mask. In this final period, Seeberg says, “the colours are like glowing charcoal”. Inspired by theosophy, and a practitioner of yoga decades before it caught on in the West, Jawlensky created works of “spiritual intensity, by hiding colour in blackness”, the curator says.

Near the end, the artist at times regained some strength, and he was able to manage dark and devastating still-lifes, a few of which will be included in the exhibition. But the centre of his work, and of his spiritual life, was the series of quickly created paintings of a single face on paper. The show will include 20 from the series where “the project became the thing”, Seeberg says.

• Alexej Jawlensky, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, 30 January-1 June