Dublin’s leading art institutions are celebrating three remarkable Irish artists—the portrait painter, patron and activist for Irish art Sarah Purser, and the modernists of a later generation Evie Hone and Mainie Jellett—who in their differing ways contributed strongly to making Ireland an international centre for contemporary art in the first half of the 20th century.

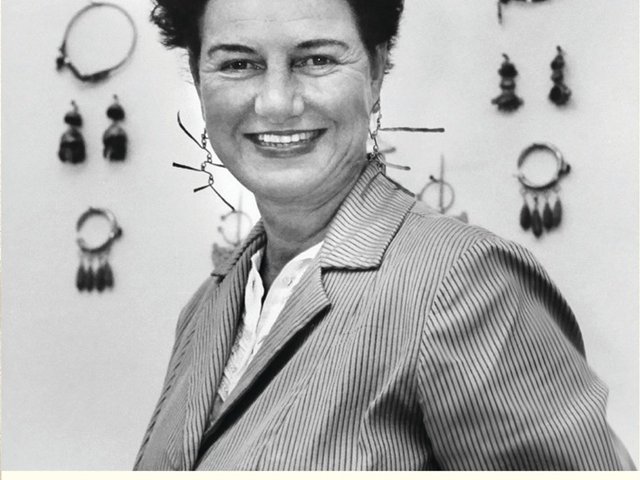

Purser (1848-1943) was one of the leading portrait painters of her generation, who trained at Académie Julian in Paris, was a self-made businesswoman, collector and encourager of artists in Paris and Dublin and co-founded the Dublin stained glass collective An Túr Gloine. She is the subject of More Power to You: Sarah Purser, a force for Irish Art (until 5 January), at the Hugh Lane Gallery. It is an exemplary monograph of her life, her creative circle, the art she loved and her own remarkable creative output. The exhibition takes the visitor from the Dublin of the 1880s and 1890s—when Purser's cousin Walter Osborne and her friend John Butler Yeats, father of the poet WB Yeats and the artist Jack B Yeats, were two of the leading artists of their day—to the work of the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland, which Purser founded in 1924, and which, a century on, continues to add representative works of modern European painting and Irish contemporary art to Irish public institutions.

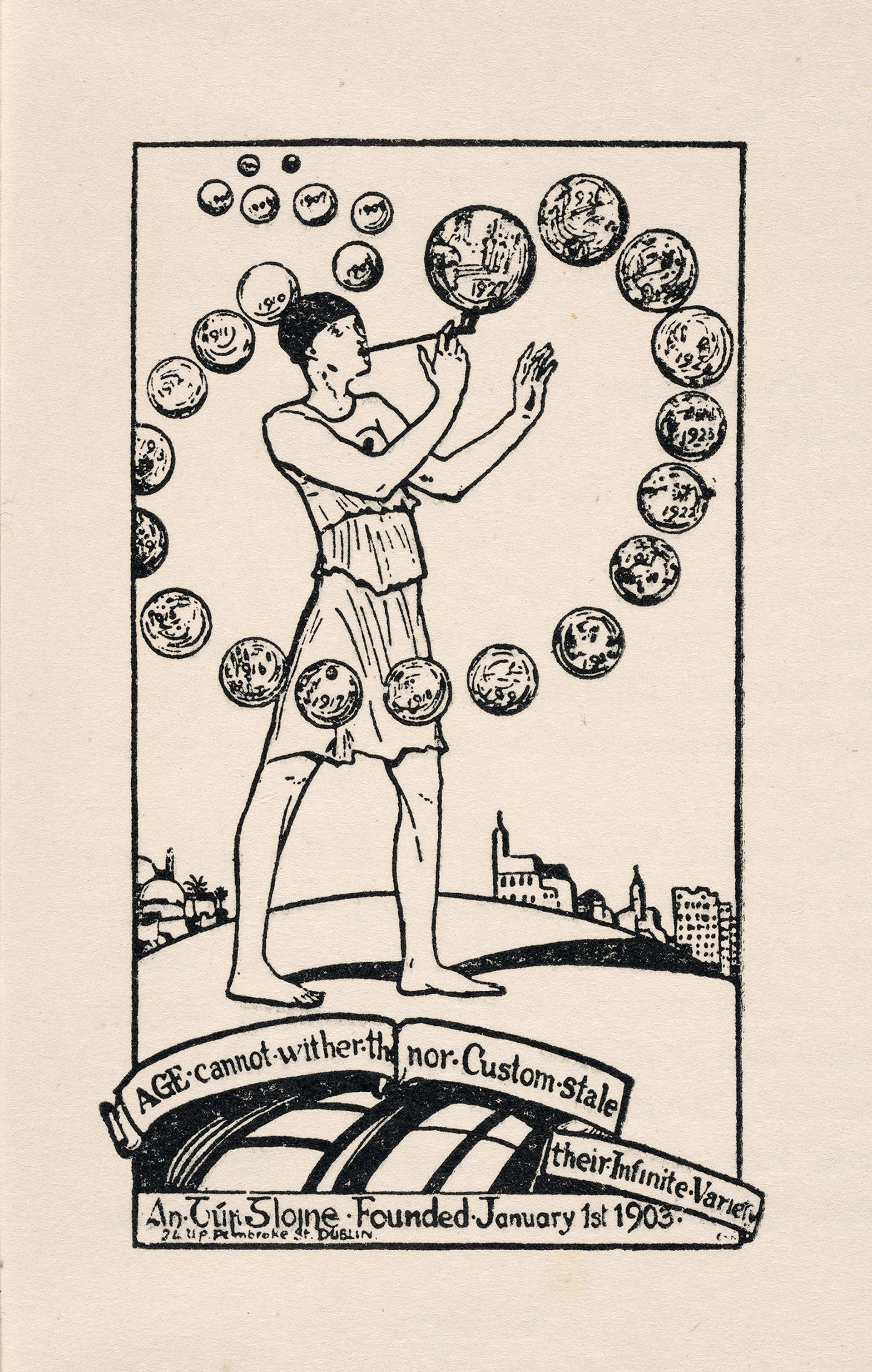

An undated photograph of the An Túr Gloine studio, the stained-glass collective in central Dublin co-founded in 1903 by the artist Sarah Purser. For 10 years from 1933 it was the working base of Evie Hone, who became a stained glass artist of the first rank before her death in 1955 National Gallery of Ireland Collection

The work of An Túr Gloine (the Tower of Glass)—co-founded by Purser and the playwright and republican activist Edward Martyn in 1903 to establish first-rate stained-glass work in Dublin in competition with the Birmingham- and Munich-based companies that had dominated so many 19th-century church commissions in Ireland—is also celebrated in An Túr Gloine: Artists and the Collective at the National Gallery of Ireland (until May 2025). The collective, which became Purser’s daily work for nearly 40 years, more than met its brief, receiving commissions from around the world and forming a first-rate Arts and Crafts arm of the Gaelic cultural revival which was famously marked by WB Yeats’s championing of new Irish drama at the Abbey Theatre. An Túr Gloine became home at various stages to three exceptional artists in stained glass: Michael Healy, Wilhelmina Geddes and Evie Hone.

By the time Hone (1894-1955) joined An Túr Gloine in 1933 she had begun to focus largely on stained glass work and was already established as a painter in artistic circles in London, Dublin and Paris. She had studied with Walter Sickert, Bernard Meninsky and Glen Byam Shaw in London after which she and her friend Mainie Jellett (1897–1944)—they met in Sickert’s studio—worked first in 1921 with André Lhote in Paris and then, for months at at a time, on and off for a decade, with his fellow Cubist Albert Gleizes.

Jellett and Hone will be the subject of Mainie Jellett & Evie Hone – The Art of Friendship, from 10 April at the National Gallery of Ireland, bringing together 90 of the two artists’ works drawn from loans and the gallery’s own holdings. After their French years with Gleizes (in Paris and the south of France) the two remained close friends until Jellett’s death in 1944. While Hone transitioned to stained glass, religious subjects and a broader area on the figurative-abstract spectrum, Jellett in turn added figurative religious and landscape elements to her fundamentally Cubist work, including her Achill Horses (1941), one of the most beloved images in the National Gallery of Ireland’s collection.

Mainie Jellett, Western Procession (undated). Jellett and her friend Evie Hone studied in the 1920s with the French Cubists André Lhote and Albert Gleizes Photo: National Gallery of Ireland

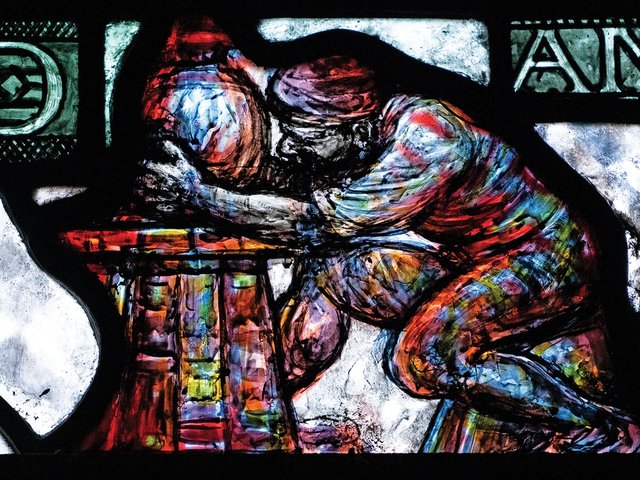

Hone, an admirer of the work of Juan Gris and Georges Rouault, was a member of the Seven and Five Society—alongside Henry Moore, Ben and Winifred Nicholson—in London from 1926 to 1932, by which time she had begun to move from strictly abstract work towards a bold, unadorned figurative style. Her My four green fields (1938), a stained-glass window commissioned by the Irish government to represent the four provinces of the island of Ireland, exhibited at the New York World's Fair in 1939 and now sited prominently in Government Buildings in Dublin, shows Hone using colour in an abstract mode with nods to medieval French glass and to Byzantine icon work.

After the Second World War, Hone received a number of commissions to replace large-scale windows in bomb-damaged English churches, and produced the work of world importance on which much of her reputation lies. She was admired by fellow artists—John Piper collected her work—and leading collectors of contemporary art and the 950 sq. ft window she produced for Eton College Chapel, on the subjects of Christ’s Last Supper and Crucifixion (1949-52) is a masterpiece of mid-20th-century art.

Evie Hone, East Window (1949-52), Eton College Chapel, Berkshire Homer Sykes / Alamy Stock Photo

Installed in an historic 15th-century church building founded by Henry VI, which had lost all its glass when bombs fell nearby in December 1940, Hone’s Eton windows wowed artists and critics alike with the power with which she composed in coloured glass on a grand scale. In the process she managed to address, without compromise, the past and present of art, with what felt to many contemporaries like an optimal blend—for that moment and for that imposing gothic space—of the abstract and figurative. She managed in the process to serve both her expressive muse and the contemplative, mysterious nature of the finest religious narrative art. Two other international commissions Hone received in this period are the great rose window (1952) for Farm Street Church, in London’s Mayfair, and a two-light window the following year depicting the Raising of the Daughter of Jairus for the Washington National Cathedral in the US capital.

A century of art

"More Power to You", in the title of the Purser show, refers to a comment she made in a letter to her friend the art dealer and collector Hugh Lane, whose plans for the Municipal Art Gallery of Modern Art in Dublin (now the Hugh Lane Gallery) she supported and pushed through after his death in the sinking of the Lusitania by a German U-boat in 1915. In “Sarah Purser and Hugh Lane”, Robert O’Byrne’s essay in the exhibition catalogue, edited by the show’s curator, Logan Sisley, O’Byrne establishes that the Hugh Lane Gallery would likely not exist without Purser’s dogged advocacy, both early in the century and then in suggesting and securing Charlemont House as its permanent home in Parnell Square, opened in 1933.

Purser was nearly a half-century older than Hone and Jellett but many of the challenges that she faced—misogyny in art schools and artistic associations and the conservative nature of both critics and curators—remained intact when Hone and Jellett came to maturity. Purser’s experiences in bringing an Art Loan Exhibition of international art to Dublin in 1899—with work by artists including Edouard Manet (including his 1866 Madame Manet), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and Purser’s friend Louise Breslau—and in helping Hugh Lane to bring the world’s first municipal gallery of modern art into being in 1908—the mix of critical incomprehension, bafflement and thinly veiled hostility—seem to have matched the dismaying critical experience for Roger Fry in mounting Manet and the Neo-Impressionists exhibition in London in 1910.

Sisley, head of exhibitions at the Hugh Lane Gallery, emphasises that so many of Purser’s activities as a curator and promoter of shows were a “precursor to Lane's activity. She had been active in terms of exhibition making.” In 1901, she pulled together an exhibition of the work of the landscape artist Nathaniel Hone and of John Butler Yeats, two of the senior figures in Irish art. John Butler Yeats had had work rejected by the Royal Hibernian Academy, which Purser found outrageous. And she felt that Hone, who had made his name working with the Barbizon School in France, was no longer properly appreciated at home. “So she organised,” Sisley tells The Art Newspaper, “paid for an exhibition, paid for the space, the catalogue, organised the work, lent works herself by Hone and Yeats.”

Wilhelmina Geddes, Their Infinite Variety, an illustration for the An Túr Gloine 25th anniversary booklet, 1928 The Brothers Kerr. National Gallery of Ireland Collection

When Jellett showed two of her Cubist works at the Dublin Painters' Exhibition in 1923, they were greeted with hostility by the critic of The Irish Times. When she and Hone showed together the following year—the year of the first Tailteann Games launched by the Irish Free State, a mix of sports and culture, and featuring appearances from WB Yeats and the artist Augustus John—the sense of critical bemusement was no less marked. George Russell, the grand old man of Dublin scholarly journalism and intellectual life, an internationally admired editor who had been an ally of Purser’s in putting on the 1899 international exhibition in Dublin, wrote in the Irish Statesman, that “the real defect in this form of art is that the convention is so simple that nothing can be said in it”. Both artists, as ever unabashed, exhibited extensively internationally during the 1920s, and were in the vanguard at exhibitions in London and Paris such as the Salon des Indépendants and L’Art d’Aujourd‘hui (1925), alongside Gleizes, Delaunay and Leger.

Purser and the Yeats family

Purser, Jellett and Hone came from Protestant families of the Ascendancy Dublin haut bourgeois which was losing even in Purser’s early life its outsized share of the fruits of commerce and the professions in Ireland. It was the same world that produced the Yeats family of artists and poets. But Purser, as the historian Roy Foster explains in his vivid catalogue essay, “Sarah Purser’s Worlds”, managed to bridge many streams in the Protestant-Catholic and Establishment-Republican divides of late 19th and early 20th-century Ireland. Sometimes, it would seem, this was through sheer force of personality as much as her love of her country and its culture.

Sarah Purser, portraits of her friends the poet WB Yeats (1898, left) and the object of his unrequited love, the revolutionary Republican campaigner Maud Gonne (1898) Hugh Lane Gallery

Purser, as Foster recounts, was one of the few people who could put her celebrated revolutionary Republican friend Maud Gonne in her place. When Gonne was staying with Purser in Dublin in 1898, Purser made pastel portraits of both Gonne and her famously frustrated suitor WB Yeats. And 11 years later, when Gonne entertained Yeats and Purser in Paris—a city where Purser kept up long-standing connections with artist friends including Edgar Degas—Yeats recounted to his father: “She was as characteristic as ever … Maud Gonne had a cageful of canaries and the birds were all singing. Sarah Purser began lunch by saying ‘What a noise! I’d like to have my lunch in the kitchen.’”

One question that might be resolved by the curators of the upcoming Jellett-Hone show—or by Joseph McBrinn, author of a critical study of Hone due to be published by Four Courts Press later this year—is just why Purser had been so resistant to Hone joining An Túr Gloine when she first made an approach in the 1920s to make some panels she had designed. It may in part be because Purser had seen that clients might all too soon come calling for the quietly spoken but charismatic Hone’s outsize talent rather than for the work of the collective as a whole. For whatever reason, Hone started her stained-glass apprenticeship not in Dublin but with a brilliant protégée of Purser’s, Wilhelmina Geddes (1887-1955), who had moved to London in 1925 after 15 years at An Túr Gloine, and whose vivid personality and boundary-breaking work stands out both in the Purser show at the Hugh Lane and in the An Túr Gloine exhibition.

Neither Jellett nor Hone ever compromised as artists. Both established reputations of their own in the international avant-garde, while Jellett in particular preached the lessons of modernism at home and abroad. In 1943, piqued at the conservatism of the Royal Hibernian Academy (founded in 1823) and the work shown at its annual exhibition, they co-founded, with Norah McGuinness, Louis Le Brocquy and other artists, a salon des refusés of their own, the Irish Exhibition of Living Art.

Both Jellett and Hone's work is well represented in the collections of the Hugh Lane Gallery and the National Gallery of Ireland, as well as that of the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Their joint exhibition, the first since they showed together in Dublin in 1924, promises to demonstrate both their shared artistic integrity as well as the combined scholarly power of a museum ecosystem in Dublin that Purser—who, as well as being one of the prime begetters of the Hugh Lane Gallery and founder of the Friends of the National Collections of Ireland, was a director for many years of the National Gallery of Ireland—did so much to foster.

- More Power to You: Sarah Purser—A Force for Irish Art, Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin, until 5 January

- An Túr Gloine: Artists and the Collective, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, until May

- Mainie Jellett & Evie Hone—The Art of Friendship, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin, 10 April-10 August