There are worse ways to spend a winter afternoon by the fire than wandering the rooms depicted in the architectural historian Steven Brindle’s massive and bewitching London Lost Interiors: the homes of aristocrats, society figures, eccentrics, artists, and a few mere millionaire stockbrokers and diamond dealers. The rooms are showcases for opulence, but in most cases they are less about individual taste than the means to hire the most expensive and fashionable interior decorators of the day. In a block of luxury flats built for Edwina Mountbatten on Park Lane, the rooms of Rebecca Sieff—whose husband would develop a modest, inherited retail company into Marks & Spencer—were decorated by the architect Edwin Lutyens and interior designer Syrie Maugham, a team famous for chilly all-white rooms, while the Mountbattens upstairs had colourful Rex Whistler murals.

What these wildly different spaces have in common is that they are gone. Of all the buildings still standing, only one is occupied by the original family: Apsley House, “Number 1, London”, once the home of the “Iron” Duke of Wellington of Waterloo fame. Partly a museum, it is still home to the present duke, who contributes a not particularly illuminating foreword to this volume. Otherwise, most of the buildings and all the rooms have vanished. Many were blown to smithereens in the Blitz, but, as Brindle comments sadly, any survivors “were dinosaurs”, too big to heat or staff, their bells calling servants who would never again clear dining tables set for 40. Developers flattened many more, and where buildings survive, changing fashions swept away the interiors, although occasionally one senses Brindle standing on tiptoe peering over garden walls where he suspects elements of original schemes may survive.

Gutted and gone

Many contents went with the rooms. Serge Chermayeff—the Russian-born architect and creator with Erich Mendelsohn of the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill—designed an elegantly plain Modern Movement interior in 1937 within the Georgian walls of 5 Connaught Place in Bayswater, knocked through vertically to form a double-height living room focused on a large Picasso. The house, in Brindle’s terse summary of its fate, “was severely damaged by bombing, and subsequently abandoned and demolished”. The Picasso vanished with its home.

There were some surprising survivals. The most startling of the extraordinary decorations of Mulberry House in Westminster, an Art Deco transformation by the architects Darcy Braddell and Humphry Deane of a 1911 Lutyens house, was also thought blitzed. Embedded in the foil-covered walls, the sculptor Charles Sargeant Jagger contributed Scandal, a bas relief of naked lovers clinging together surrounded by malevolent faces hissing disapproval. It was commissioned by Henry Mond, an heir to the Imperial Chemical Industries fortune, and his wife Gwen to represent society reaction to their earlier ménage à trois with the writer Gilbert Cannan. Thought lost, it resurfaced in a New York auction in 2008 and is now on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

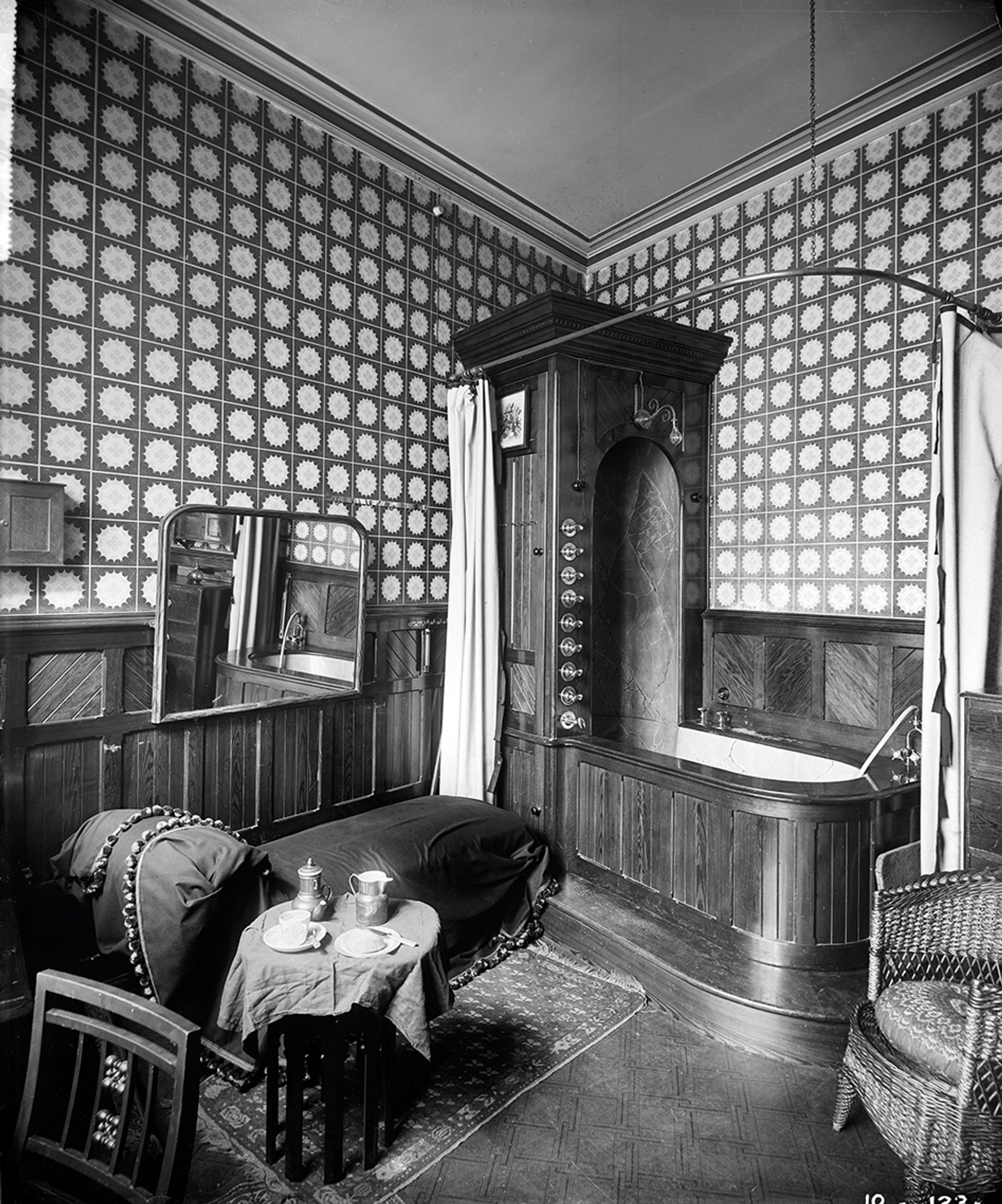

Major George Wallace Carpenter’s bathroom at 28 Ashley Place, Westminster, in 1893

Photo © Historic England

Many of the rooms are just too much: too much money, too much furniture, too much stuff. The rare photographs of bathrooms and kitchens—such as the one taken in 1893, which shows the splendid mahogany-panelled bath at 28 Ashley Place (the home of Major George Wallace Carpenter), or Mrs Vernon Tate’s delightful 1930s kitchen at 7 Princes Gate—provide a welcome breather from the dizzying procession of drawing rooms with no swag unfringed, no mirror ungilded.

Descent into vulgarity

Two remarkably plain 1930s rooms—only softened by a few chintz-covered armchairs and a teddy bear—were the new day and night nurseries of a one-year-old baby, the future Queen Elizabeth II, when her parents, then Duke and Duchess of York, moved into the grand 18th-century 145 Piccadilly. The family left—presumably with the chandeliers in their luggage—in 1936 to move across Green Park to Buckingham Palace, when the duke reluctantly became King George VI on the abdication of his brother. The house barely outlived them. The future queen wrote that she wished the bomb that destroyed it had hit the German Embassy instead: “I believe the interior has been made very vulgar by that horrible Ribbentrop & it would have been no loss.”

Obviously one yearns to see that vulgar interior, and 200 pages further on, this fascinating book permits just that, the startling remodelling of 7 Carlton House Terrace by Adolf Hitler’s favourite architect, Albert Speer. It was his only work outside Germany, for Joachim von Ribbentrop, the Third Reich’s ambassador to Britain. The work, at a cost of five million Reichsmarks, was celebrated in 1937 with a reception for 1,400 guests. Brindle believes the photographs were taken in 1939 when the Crown Estate hastily reclaimed the building, but it still contained its swastika-bordered stair carpet, German furniture like that chosen by Hitler for his Bavarian retreat, Berchtesgaden, and a fireplace with a swastika frieze, which astonishingly survived until 1964. Some losses are mourned more than others.

• London Lost Interiors, by Steven Brindle. Published by Historic England/Atlantic Publishing,416pp, 650 illustrations, £50 (hb), 4 November 2024