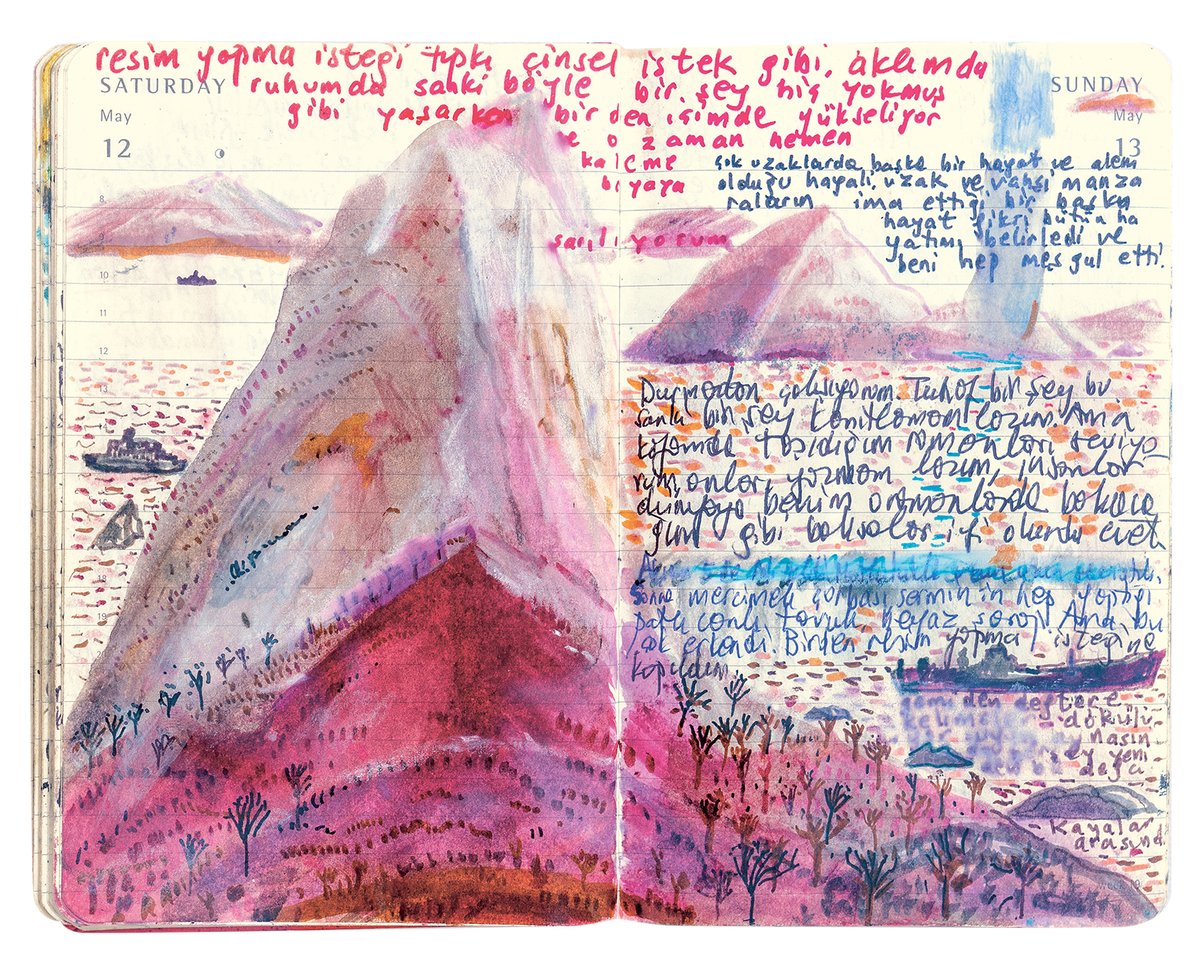

Orhan Pamuk, Turkey’s most famous living novelist, has always had a secret passion. The author of best-selling books such as My Name is Red, Nights of Plague and Snow is also an artist, producing numerous illustrated notebooks covering the period from 2009 to 2022. Every day during that time, Pamuk wrote and drew in his Moleskine notebooks, creating William Blake-esque doodles that reflect a range of experiences such as taking friends to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art or travels to countries such as India.

These illustrations, along with Pamuk’s candid texts, have been combined into one volume entitled Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks. “Ekin Oklap’s translations swarm playfully around the reproductions of the notebook pages, arranged in cloud-like form,” says a review in the Times Literary Supplement.

“Memories of Distant Mountains is a selection from the pictured pages of my journals,” Pamuk says. “In the 400-page book, the pictures are related to each other and to texts that surround them thematically, or by a feeling or a coincidence. There is a continuity of words and pictures that I care about. The pages follow and narrate feelings, dreams, nightmares, sentiments, travels, observations—all in colour.”

Pamuk uses brush-tipped pens, pencils, crayons and watercolours to create the illustrations. “Sometimes as I write on a page, I leave a space for a drawing I will later make. Sometimes I write over a painted double page. Texts do not explain the pictures nor the pictures illustrate the texts,” he says.

Pamuk wanted to be a painter but was steered towards architecture

Photo: Jerry Bauer

The task has been challenging, stresses Pamuk, who adds that selecting the pages from more than 30 notebook volumes was a “major labour”. Putting them in a “poetic” order so that they suggest a story was another test, he says. “I did not put the pages in a chronological order. I lined them up by themes, by subjects, by sentiments, by places or even by colours. The reader, after looking at a page that was created in 2016, may next read about a similar sentiment expressed differently with a picture made in 2009.”

The book also covers difficult episodes in the author’s life. In a 2005 interview Pamuk made comments about the 1915 mass killings of Armenians and Kurds in the Ottoman Empire; he was attacked in the Turkish press and subsequently given protection in the form of three bodyguards. He annotates a street scene drawing from 2020, saying: “Here is the court where I stood trial in 2005 for talking about the Armenian genocide. People threw stones at us on the way out.” In other entries, he describes making paintings in the studio of Inci Eviner, who represented Turkey at the Venice Biennale in 2019.

Pamuk’s enthusiasm for art lay dormant for many years. “I wanted to be a painter until the age of 22,” he says. “My grandfather, my father and uncles were all civil engineers. I was expected to go to the same college, Istanbul Technical University. Since I was the black sheep, the artist in the family of civil engineers, they all said I had to go to the same university but study architecture instead of civil engineering. Suddenly, at the age of 22, I killed the painter in me and began writing novels. In the end the painter in me did not die either. But he was shy and working secretly.”

Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks by Orhan Pamuk

The notebooks also spring from another major project, namely Pamuk’s Museum of Innocence, which opened in 2012 and is based on his 2008 novel of the same name (a love story in which the narrator Kemal collects numerous items owned by his cousin Füsun). Named the 2014 European Museum of the Year, the museum houses wooden boxes related to the book’s 83 chapters. Each box is filled with items—both readymade pieces and commissioned works of art—that reflect every chapter, thereby covering a 30-year period in the history of modern Istanbul from 1975, when the novel begins.

“After it opened in Istanbul, I never put any of my own money towards the museum, which costs around €11 for a ticket,” Pamuk says. “After seeing the success of the museum and publishing its catalogue, Innocence of Objects, I thought that I now can get out of the closet as an artist and should perhaps exhibit my artistic work. Publishing these selections from my diaries was not an easy decision.”

A travelling exhibition based on the Museum of Innocence and other works Pamuk has made in the past 25 years recently opened at the Dox Centre for Contemporary Art in Prague (The Consolation of Objects, until 6 April) after stints at the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden and the Lenbachhaus in Munich. “The curators Matthias Mühling and Melanie Vietmeier came to Istanbul, looked into my archives and found things—many notebooks, photos, watercolours, sketches, landscape paintings.”

Pamuk’s journals are part of a long tradition of literary diaries. “Writers’ diaries interest me. Look at Leo Tolstoy; he was a manic diary keeper but the sad thing about his diaries is that the best parts, that I would most care about, are not written. When he was writing his best novels, Tolstoy did not write in his journals. Virginia Woolf is another hero of mine who is a great diarist,” he says. “Now, keeping a journal—using the diary form—may even be a way of inventing an experimental literary space.”

• Memories of Distant Mountains: Illustrated Notebooks, Orhan Pamuk (translated by Ekin Oklap), Faber, 384pp, £35 (hb)