The Cuban artist Zilia Sánchez, celebrated for her abstract paintings and sculptures that evoke the feminine form, has died, aged 98. Overlooked until her later years, recognition of Sánchez’s contributions to post-war Latin American modernism and feminist art have only been widely celebrated over the last decade as her work became better represented on the international circuit. While Sánchez’s practice spanned various styles and themes throughout her career, she became best-known for her works that incorporate erotically-tinged, bulbous contours.

Born in 1926 in Havana, Sánchez earned her degree from the San Alejandro National Academy of Fine Arts in 1947. She left Cuba in 1960 as Fidel Catro rose to power, living in Spain, Italy, Canada and New York, where she studied art restoration with the Herbert E. Feist Gallery and printmaking at the Pratt Institute. She settled permanently in San Juan, Puerto Rico, in the 1970s, working as a professor at the Escuela de Artes Plásticas de Puerto Rico since the 1990s and at the Art Students League of San Juan.

Sánchez’s practice spanned painting, architecture, theatre design, drawings and sculpture. But her work had been rarely seen outside of Puerto Rico prior to a survey presented at Artists Space in New York in 2013, which The New York Times critic Holland Cotter called “one of the year’s high points, a revelation and a refreshment”.

Zilia Sánchez, Eros, 1976/1998 © Zilia Sánchez. Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Sánchez joined Galerie Lelong the same year. Mary Sabbatino, the gallery’s vice president and partner, met Sánchez in San Juan and claims it became her “mission to make [Sánchez’s] paintings more widely known” to the world. “Mighty beyond her small stature, Sánchez forged an artistic path that had little recognition until her mid-80s; this should be an inspiration to many of us,” Sabbatino said in a statement.

Galerie Lelong has held two solo exhibitions of Sánchez’s work, mostly recently Eros in New York in 2019-20, which featured the artist’s first ever works in marble, a series of muted free-standing sculptures accentuated by swollen forms. The first exhibition, Heróicas Eróticas en Nueva York, was held in 2014 and focused on works Sánchez made during the eight years she lived in New York (1964-72), including a series of minimalist shaped canvases and a new monumental diptych.

Much of the artist’s work was severely damaged in 2018 during Hurricane Maria, which tore off the roof of her studio in the Santurce neighbourhood of San Juan, where she had worked for nearly five decades. With the help of her students, her studio was rebuilt, and Sánchez continued to work there until the end of her life. In 2019, her first solo museum exhibition Soy Isla (I Am an Island), which traced the artist’s travels and career from her beginnings in Cuba, premiered at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, and later travelled to the Museo de Arte Ponce in San Juan and El Museo del Barrio in New York.

Installation view, Galerie Lelong, New York, Zilia Sánchez: Heróicas Eróticas en Nueva York, 3 May-21 June 21 2014 Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co, New York.

Sánchez’s work was included in the 2019 exhibition Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, a groundbreaking traveling exhibition that premiered at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles as part of Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA. Sánchez was also featured in the central exhibition of the recently-closed 60th Venice Biennale, Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere, where her moon-shaped work Lunar (1980) was shown in the central pavilion, and participated in the 57th Venice Biennale in 2017, Viva Arte Viva.

A survey of Sánchez’s work from the 1950s to the mid-1990s opened earlier this year at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami, titled Zilia Sánchez: Topologías / Topologies. The exhibition examined the diversity of Sánchez’s output, seeking to broaden the understanding of the various contexts in which she worked throughout her life.

The artist’s death was confirmed by the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico (MAPR) on Thursday (19 December), which announced that the artist died on 18 December. The museum is in the process of bringing the ICA Miami survey to Puerto Rico, with an opening date scheduled for March 2025. It is also currently restoring her totemic two-piece sculpture Subliminar (2000), which will soon be reinstalled in the museum’s sculpture garden.

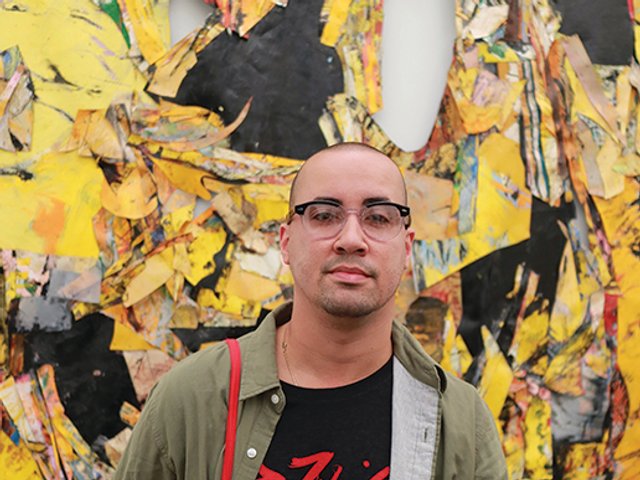

Zilia Sánchez in her studio, San Juan, 2014 Photo by Raquel Perez Puig

“From my point of view, Zilia was a pioneer and a unique voice in Caribbean and Latin American modernism,” María Cristina Gaztambide, the director of the MAPR, told El Nuevo Día in an interview. “She combined—in a very original way—the geometric abstraction and constructivist tendencies that emerged throughout the continent since the mid-20th century from a feminist perspective. That is what really remains of her legacy: she was a unique voice.”

Sánchez’s work is held in international museums including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA); the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Tate Modern; the Crystal Bridges Museum of Art; the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, and others.

“Art can be expressed through a technique or a spirit,” Sánchez said in an interview in the catalogue that accompanied the 2019 Phillips Collection show. “Technique can be taught, but an inner spirit cannot.”